Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (2 page)

Read Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin Online

Authors: Timothy Snyder

Tags: #History, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #European History, #Europe; Eastern - History - 1918-1945, #Political, #Holocaust; Jewish (1939-1945), #World War; 1939-1945 - Atrocities, #Europe, #Eastern, #Soviet Union - History - 1917-1936, #Germany, #Soviet Union, #Genocide - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Holocaust, #Massacres, #Genocide, #Military, #Europe; Eastern, #World War II, #Hitler; Adolf, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Massacres - Europe; Eastern - History - 20th century, #World War; 1939-1945, #20th Century, #Germany - History - 1933-1945, #Stalin; Joseph

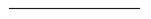

The bloodlands were where most of Europe’s Jews lived, where Hitler and Stalin’s imperial plans overlapped, where the Wehrmacht and the Red Army fought, and where the Soviet NKVD and the German SS concentrated their forces. Most killing sites were in the bloodlands: in the political geography of the 1930s and early 1940s, this meant Poland, the Baltic States, Soviet Belarus, Soviet Ukraine, and the western fringe of Soviet Russia. Stalin’s crimes are often associated with Russia, and Hitler’s with Germany. But the deadliest part of the Soviet Union was its non-Russian periphery, and Nazis generally killed beyond Germany. The horror of the twentieth century is thought to be located in the camps. But the concentration camps are not where most of the victims of National Socialism and Stalinism died. These misunderstandings regarding the sites and methods of mass killing prevent us from perceiving the horror of the twentieth century.

Germany was the site of concentration camps liberated by the Americans and the British in 1945; Russian Siberia was of course the site of much of the Gulag, made known in the West by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. The images of these camps, in photographs or in prose, only suggest the history of German and Soviet violence. About a million people died because they were sentenced to labor in German concentration camps—as distinct from the German gas chambers and the German killing fields and the German starvation zones, where

ten million

people died. Over a million lives were shortened by exhaustion and disease in the Soviet Gulag between 1933 and 1945—as distinct from the Soviet killing fields and the Soviet hunger regions, where some

six million

people died, about

four million

of them in the bloodlands. Ninety percent of those who entered the Gulag left it alive. Most of the people who entered German concentration camps (as opposed to the German gas chambers, death pits, and prisoner-of-war camps) also survived. The fate of concentration camp inmates, horrible though it was, is distinct from that of those many millions who were gassed, shot, or starved.

The distinction between concentration camps and killing sites cannot be made perfectly: people were executed and people were starved in camps. Yet there is a difference between a camp sentence and a death sentence, between labor and gas, between slavery and bullets. The tremendous majority of the mortal victims of both the German and the Soviet regimes never saw a concentration camp. Auschwitz was two things at once, a labor camp and a death facility, and the fate of non-Jews seized for labor and Jews selected for labor was very different from the fate of Jews selected for the gas chambers. Auschwitz thus belongs to two histories, related but distinct. Auschwitz-as-labor-camp is more representative of the experience of the large number of people who endured German (or Soviet) policies of concentration, whereas Auschwitz-as-death-facility is more typical of the fates of those who were deliberately killed. Most of the Jews who arrived at Auschwitz were simply gassed; they, like almost all of the fourteen million killed in the bloodlands, never spent time in a concentration camp.

The German and Soviet concentration camps surround the bloodlands, from both east and west, blurring the black with their shades of grey. At the end of the Second World War, American and British forces liberated German concentration camps such as Belsen and Dachau, but the western Allies liberated

none

of the important death facilities. The Germans carried out all of their major killing policies on lands subsequently occupied by the Soviets. The Red Army liberated Auschwitz, and it liberated the sites of Treblinka, Sobibór, Bełżec, Chełmno, and Majdanek as well. American and British forces reached

none

of the bloodlands and saw

none

of the major killing sites. It is not just that American and British forces saw none of the places where the Soviets killed, leaving the crimes of Stalinism to be documented after the end of the Cold War and the opening of the archives. It is that they never saw the places where the

Germans

killed, meaning that understanding of Hitler’s crimes has taken just as long. The photographs and films of German concentration camps were the closest that most westerners ever came to perceiving the mass killing. Horrible though these images were, they were only hints at the history of the bloodlands. They are not the whole story; sadly, they are not even an introduction.

Mass killing in Europe is usually associated with the Holocaust, and the Holocaust with rapid industrial killing. The image is too simple and clean. At the German and Soviet killing sites, the methods of murder were rather primitive. Of the fourteen million civilians and prisoners of war killed in the bloodlands between 1933 and 1945, more than half died because they were denied food. Europeans deliberately starved Europeans in horrific numbers in the middle of the twentieth century. The two largest mass killing actions after the Holocaust—Stalin’s directed famines of the early 1930s and Hitler’s starvation of Soviet prisoners of war in the early 1940s—involved this method of killing. Starvation was foremost not only in reality but in imagination. In a Hunger Plan, the Nazi regime projected the death by starvation of tens of millions of Slavs and Jews in the winter of 1941-1942.

After starvation came shooting, and then gassing. In Stalin’s Great Terror of 1937-1938, nearly seven hundred thousand Soviet citizens were shot. The two hundred thousand or so Poles killed by the Germans and the Soviets during their joint occupation of Poland were shot. The more than three hundred thousand Belarusians and the comparable number of Poles executed in German “reprisals” were shot. The Jews killed in the Holocaust were about as likely to be shot as to be gassed.

For that matter, there was little especially modern about the gassing. The million or so Jews asphyxiated at Auschwitz were killed by hydrogen cyanide, a compound isolated in the eighteenth century. The 1.6 million or so Jews killed at Treblinka, Chełmno, Bełżec, and Sobibór were asphyxiated by carbon monoxide, which even the ancient Greeks knew was lethal. In the 1940s hydrogen cyanide was used as a pesticide; carbon monoxide was produced by internal combustion engines. The Soviets and the Germans relied upon technologies that were hardly novel even in the 1930s and 1940s: internal combustion, railways, firearms, pesticides, barbed wire.

No matter which technology was used, the killing was personal. People who starved were observed, often from watchtowers, by those who denied them food. People who were shot were seen through the sights of rifles at very close range, or held by two men while a third placed a pistol at the base of the skull. People who were asphyxiated were rounded up, put on trains, and then rushed into the gas chambers. They lost their possessions and then their clothes and then, if they were women, their hair. Each one of them died a different death, since each one of them had lived a different life.

The sheer numbers of the victims can blunt our sense of the individuality of each one. “I’d like to call you all by name,” wrote the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova in her

Requiem

, “but the list has been removed and there is nowhere else to look.” Thanks to the hard work of historians, we have some of the lists; thanks to the opening of the archives in eastern Europe, we have places to look. We have a surprising number of the voices of the victims: the recollections (for example) of one young Jewish woman who dug herself from the Nazi death pit at Babi Yar, in Kiev; or of another who managed the same at Ponary, near Vilnius. We have the memoirs of some of the few dozen survivors of Treblinka. We have an archive of the Warsaw ghetto, painstakingly assembled, buried and then (for the most part) found. We have the diaries kept by the Polish officers shot by the Soviet NKVD in 1940 at Katyn, unearthed along with their bodies. We have notes thrown from the buses taking Poles to death pits during the German killing actions of that same year. We have the words scratched on the wall of the synagogue in Kovel; and those left on the wall of the Gestapo prison in Warsaw. We have the recollections of Ukrainians who survived the Soviet famine of 1933, those of Soviet prisoners of war who survived the German starvation campaign of 1941, and those of Leningraders who survived the starvation siege of 1941-1944.

We have some of the records of the perpetrators, taken from the Germans because they lost the war, or found in Russian or Ukrainian or Belarusian or Polish or Baltic archives after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. We have reports and letters from German policemen and soldiers who shot Jews, and of the German anti-partisan units who shot Belarusian and Polish civilians. We have the petitions sent by the communist party activists before they enforced famine in Ukraine in 1932-1933. We have the death quotas for peasants and national minorities sent down from Moscow to regional NKVD offices in 1937 and 1938, and the replies asking that these quotas be increased. We have the interrogation protocols of the Soviet citizens who were then sentenced and killed. We have German death counts of Jews shot over pits and gassed at death facilities. We have Soviet death counts for the shooting actions of the Great Terror and at Katyn. We have good overall estimates of the numbers of killings of Jews at the major killing sites, based upon tabulations of German records and communications, survivor testimonies, and Soviet documents. We can make reasonable estimates of the number of famine deaths in the Soviet Union, not all of which were recorded. We have Stalin’s letters to his closest comrades, Hitler’s table talk, Himmler’s datebook, and much else. Insofar as a book like this one is possible at all, it is thanks to the achievements of other historians, to their use of such sources and countless others. Although certain discussions in this book draw from my own archival work, the tremendous debt to colleagues and earlier generations of historians will be evident in its pages and the notes.