Blood Secret (18 page)

Authors: Kathryn Lasky

J

ERRY’S HAND SHOOK

. She looked down at the doll. Her mind was still with Jeraldine. She stood beside that girl in the dusty road. She stood beside her and tried to help her remember all the good things that her brother had done—the arms that had lifted her up to reach the fruit on the branches of the peach tree that grew in their backyard, the voice that had woven itself like silk through the long nights when she had had pneumonia, reading to her endless stories, fairy tales and myths. This was a myth, wasn’t it, that was happening right now? Fernando was disappearing and then he would magically reappear. Yes, the peach from the tree would split open and Fernando would step out. Jerry shook her head. It was now Saturday. Holy Saturday. In a few hours she and Constanza would go to church for the service of light, the Easter vigil.

“Amigos,” Padre Hernandez welcomed them outside the church where a large fire burned. “Welcome on this our most holy night, when our Lord Jesus passed from death to life. We come together now in vigil and prayer. We honor the memory of his death and celebrate the resurrection…. We celebrate this holiest of the mysteries, and rejoice in that which cannot be fully understood but indeed brings the power of our Lord closer to us…and let us now pray as this fire is blessed from which we shall light the paschal candle…. Father, we share in the light of your glory through the light of your Son Jesus Christ. May blessings descend on this lighted candle and may the light from this fire inflame us with hope and love and may Almighty God and his son look down upon us through this light and shine through our long night, dispel the darkness and illuminate our souls….”

Jerry closed her eyes tight. The fires would not diminish; huge bonfires blazed in her mind’s eye. Bodies became ashes. The ashes swirled up into the sky. When Jerry and her aunt stepped out of the church after the service of the vigil, it was dark. The few stars that had begun to appear at twilight

were beginning to vanish, their frail light sucked into the blackness of the night. Constanza walked slowly. A heaviness seemed to have settled upon her. She seemed smaller. It was as if she had shrunk within her own body and now was exhausted from dragging around something that was simply too large. Had she been wrong in telling Constanza all that she had discovered in the cellar? Was it simply too much for the old woman? They drove silently home. Constanza went straight to bed, hardly muttering a good night. Jerry watched as the door to her aunt’s bedroom closed. She must go to the cellar now.

She descended the stairs. She knew it would be the last time. She lifted the lid of the trunk and picked up the corncob doll worn from its years of strange, obsessive, misplaced love.

Jerry

I am stepping through a window of memory, my own memory…. When I stopped speaking, the words dropped away one by one, dropped away against a great wall of meaninglessness. Yes, one by one they dropped away and then there was silence. I did not have to hear my mother, not only her

words unspeakable, although she spoke them, but her footsteps as she walked away, cradling her favorite doll. She had left the others for me. But still she walked away. No hesitancy, although she appeared to amble. That was her way—ambling. It was noon when Mother left me, and time seemed to stop. The sun congealed in a colorless sky. It was like a big yellow squawk and then there was silence. “Bye” was the first word I swallowed into that long silence. It simply froze on my lips as I watched my mom walk down the path to the road. I watched her until she grew into a dot, but oddly enough I felt as if I was the one who was vanishing into nothingness. There was this vast emptiness and it simply swallowed me into its silence. And that was all. My mother was gone.

So now I’ve told you about my mother and how the skirt, the stupid long skirt swirled around her ankles as she stood in the path and waved good-bye….

Jerry set the corncob doll down. She felt a wind on her shoulder. It startled her. How could there be a draft down here in the cellar? And then she heard the creak of the stairs.

“Aunt Constanza?”

“Yes, dear, I’m coming down. It’s time…it’s time…it’s time I looked in the trunk.”

She came over to where Jerry knelt and folded her long legs until her knees looked pointy through the thin fabric of her skirt. Her hand darted out to a piece of paper Jerry had never even noticed that had stuck to the inside wall of the trunk. “That must be a page from Jeraldine’s diary there, you know, my sister, your great-grandmother.” Carefully she peeled off the paper. It was unreadable except for a few words.

“Her handwriting is just like yours, Aunt Constanza.”

“Yes, but it’s hers. Not mine. She was crazy as a bedbug. I told you that already. But smart. Smart as a whip. She had a sweet husband, part Navajo, part Tewa, too; that’s how we’re related to Margaret Santangel. They ran a gift shop up by the Santuario at Las Trampas. Good business, especially during Holy Week. Lot of people make pilgrimages there. They believe that the earth is

tierita bendit

, as they say—sacred earth, you know. Lot of Indians, including Margaret Santangel, believe in its healing powers. She gets her nephew to go over and dig it up.”

“What does it heal?” Jerry asked.

“Oh.” A dark light did a jig in Constanza’s eyes. “I think it’s just an old superstition.”

A smile played across Jerry’s face. “You do?”

Constanza shrugged her shoulders and looked up. “Who knows. Let’s go up now.”

They stood outside in the cook yard. Lacy clouds raced overhead and puffs of tumbleweed chased across the dry scrubland until fetching up on the

chamisa

. The breeze carried the scent of sagebrush, and Jerry and Constanza felt the warmth of the early sun of the new day on their faces. They heard a car coming down the road and saw a cloud of red dust rising.

“Oh Lord. Here comes Sister Evangelina.” Constanza sighed.

Two minutes later Sister Evangelina pulled into the drive. She leaned out the window. “You don’t look ready for church.”

“We’re not,” Constanza replied.

“Well, get ready, dear; we’ll be late. Easter Sunday after all.”

“So it is,” Constanza replied.

Sister Evangelina leaned farther out the window and peered hard at Constanza. “Constanza, what’s going on with you?”

“Not much.”

“Well, come on then.”

“We’re not going, Sister Evangelina.” Jerry looked at her aunt. Was she really saying this? “Jerusalem and I are staying here.”

Sister Evangelina looked completely confused. She started up the car. Then there was the sound of grinding gears and the car stopped. She leaned out the window again. “What did you just call your niece?”

“Jerusalem. I called her Jerusalem.”

T

HE

N

AVAJOS BELIEVE

that when the world was created, the people traveled through four worlds before climbing a reed from the bottom of the lake known as Changing Waters to this present world. They say that First Man and First Woman came with their first two children, who were called Changing Twins, and that they, First Man and First Woman, fashioned a mountain with their own hands from the earth, and they filled it with plants and animals. On the peak they placed a black bowl with two blackbird eggs in it. They held down the peak with a rainbow. One twin took some clay from a riverbed and made it into a bowl. The other twin found reeds growing and shaped them into a water basket. They picked up stones from the ground, and with these they chiseled axes, knives, spear points, and hammers.

Sometimes I feel like those First People. I feel as if I have climbed up through worlds, through

windows in time. I have traveled to the edges of vast distances where borders are blurry and voices are muted. Through some mystery, through my silence, perhaps, I blew life into these people. They became animate. Their blood coursed, and as it did it coursed through me and I learned our secret. And here is a truth: In our secret selves we can grow old while we are still young; we can cross borders that no one else can see. We can hear voices that have long been silent. And that is what, I think, I have done.

Do you know how some people can see shapes in the clouds? Well, I see them in the shadows. The shadows cast by the clouds on the mountains or on the desert. The shadows become different when they are cast this way. They tell different stories. A cloud like a flying rabbit becomes a hooded figure in a shadow story, or perhaps an angel with wings.

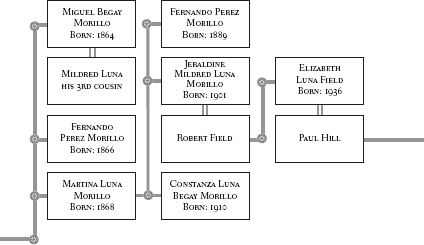

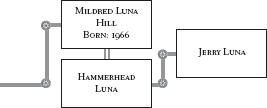

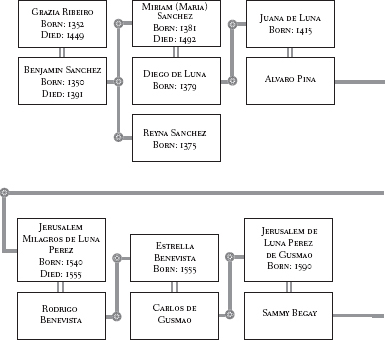

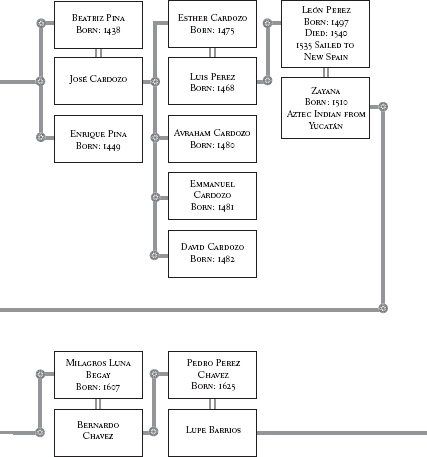

Our family has the blood of many different peoples in its veins—Hispanics, both Jews and Catholics, and Indians, Aztec and Navajo and those of the pueblos. However, because of our long blood secret, I do not think that we come from the earth like the First People of the Navajo, nor from Adam’s rib as the Bible says. I think we come from the shadowlands.

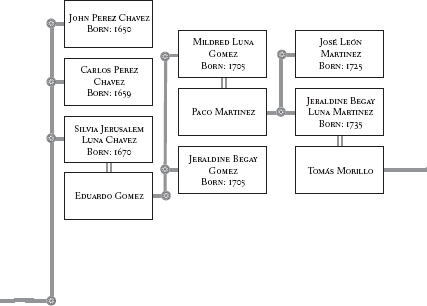

Descendants of Grazia Ribeiro

Descendants of Grazia Ribeiro

Descendants of Grazia Ribeiro