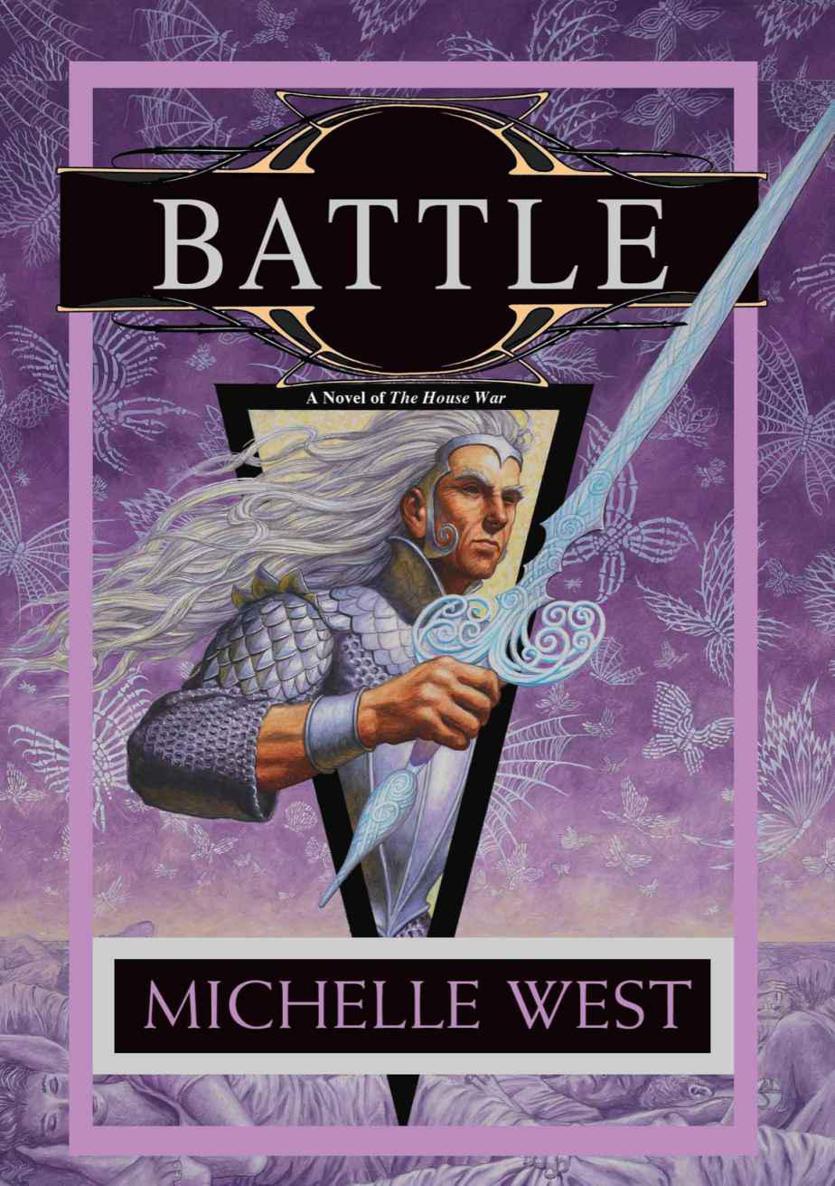

Battle: The House War: Book Five

Read Battle: The House War: Book Five Online

Authors: Michelle West

The Finest in Fantasy From

MICHELLE WEST:

The House War:

The Hidden City (Book One)

City Of Night (Book Two)

House Name (Book Three)

Skirmish (Book Four)

Battle (Book Five)

War (Book Six)*

The Sun Sword:

The Broken Crown (Book One)

The Uncrowned King (Book Two)

The Shining Court (Book Three)

Sea Of Sorrows (Book Four)

The Riven Shield (Book Five)

The Sun Sword (Book Six)

The Sacred Hunt:

Hunter’s Oath (Book One)

Hunter’s Death (Book Two)

* Coming Soon From DAW

BATTLE

A House War Novel

MICHELLE WEST

Copyright © 2013 by Michelle Sagara.

All Rights Reserved.

Cover art by Jody Lee.

DAW Book Collectors No. 1610.

DAW Books are distributed by Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Book designed by Elizabeth Glover.

All characters in this book are fictitious.

Any resemblance to persons living or dead is strictly coincidental.

The scanning, uploading and distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal, and punishable by law. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage the electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

For my aunts:

Fujiko Harada

and

Nobuko May Sagara

Absent but never forgotten.

Acknowledgments

M

y life has been deadline heavy in the past year, in part because turning a creative art into a professional one can be fraught. If things work relatively smoothly, the butt-in-chair school of writing works, and absent the usual writing stresses, everyone is more or less happy. When things don’t work, they have to be fixed, and if they don’t work several times, they have to be fixed several times, which leads to a sudden, rushing vacuum where all the time used to be.

So: for keeping me as sane as I generally get when things are exploding or burning down, thanks go to Ken and Tami Sagara, Thomas, and Terry; to Kristen and John Chew for feeding us all on Mondays, for Daniel and Ross who have a much more realistic and unromantic view of a writer’s life (my favorite comment was Daniel’s, “Mom, could you

try

to be a little more objective about your own work?” when the hair-pulling had reached epic proportions).

For sanity beyond the realm of the “Oh. My. God this is

never

going to fit in one book” terror, Sheila Gilbert, my long-time editor and friend at DAW, and Joshua Starr. And Jody Lee, of course, for her beautiful art.

Prologue

24th of Henden, 427 A.A.

Terrean of Averda

T

HE TREE STOOD ALONE in the moonlight. The forest with which it had once been surrounded had withered; dead trees, trunks hollowed, shed dry branches in a circle for yards. Little grass or undergrowth survived in the lee of the tree; no insects crawled along its bark; no birds nested in its slender branches. It lived, yes, but its life was almost an elegy. Where wind dared to touch it, no leaves rustled; it gave nothing back.

Nothing but illumination. Light extruded from bark that seemed, at a distance, to be composed of ice; from branches that seemed sharp and slender, like long, narrow blades. There were leaves on those branches, and in the moon’s light, they looked silvered, their edges inexplicably dark. The tree cast a long shadow over silent ground.

Into that shadow two men walked. One wore robes that seemed to draw moonlight into its weave; one wore dusty, sweat-stained cloth. The latter was armed, although this unnatural clearing was utterly silent. Both men paused ten yards from the tree, scanning the ground that surrounded it.

“Can you hear it?” Meralonne asked softly, his gaze held by the Winter tree.

His companion closed his eyes. After a brief pause, he nodded.

“And?”

“Like the others, it cannot be saved. It sings of cold, of isolation, of fear. It will devour all in its attempt to appease its hunger.” His breath sharpened as the mage approached the tree, one hand raised. “APhaniel—”

“If it cannot be saved, it must be destroyed.”

Kallandras said nothing. Meralonne APhaniel habitually guarded the tone of his words, but it had been a long six days, and even he had grown weary. The bard, not the mage, whispered a benediction to the wind, and the wind intervened. It lifted the mage off the ground a moment before the earth beneath his feet broke and roots crested its surface, moving like misshapen snakes.

“APhaniel,” he said again, cajoling the mage as he might cajole the wild wind at its most reluctant, “This tree cannot be saved.”

The mage proved more truculent than elemental air; he would not be moved. Roots coiled beneath his feet, snapping at the underside of boots they couldn’t quite reach. Like the tree they sustained, they were silver, their luminescence veiled by dirt.

“APhaniel—”

The mage turned, eyes flashing as if they were diamond in clear, sunlit sky—hard, bright, cold. And beautiful. Always that. Kallandras fell silent.

Taking a step into air, the bard cleared ground, hovering above it, weapons ready. If Meralonne was unwilling to countenance the certainty of failure, the bard was not. He remained silent; the single glance had been warning enough. Even when roots erupted in a frenzy beneath his feet, piercing the air upon which he now stood, he did not speak a word—not to the mage.

He spoke to the roots, but he spoke in the silence granted any of the bard-born; only the tree itself could hear what he said, and the answer offered was the sharp thrust of those roots toward his chest; they were hard and sharpened, like long, curved knives, and their tips glittered in the radiant light of the tree’s bark. His blades cut three, and slid off three more; he leaped up to a height that the roots couldn’t easily follow. Given time, they would; that much, he’d gleaned in the last week, working in secrecy on the borders of the Terrean.

But Meralonne had reached the tree’s trunk. The roots that Kallandras severed barely troubled the mage; they did not attempt to pierce, but rather to ensnare. He had gathered them loosely as he moved, and they pooled around his ankles, obscuring his boots, as if the tree were trying to absorb him, to make him some part of its essential self.

Meralonne did not speak. Kallandras knew why: in this place, at this time, he could no longer guard his voice; every word contained the pain of loss and the slow, steady death of hope. The mage reached out with both hands; his palms touched the ice of bark and light shone where they connected; it was bright and piercing to the eye, as the roots meant to be to the heart. The momentary dimming of vision did not impede the bard’s weapons; they were meant for this fight, and they moved almost with a will of their own.

The light that was pale and even platinum began to shift and change; what remained beneath the palms of the mage was a red-copper that pulsed. Kallandras had seen that steady transformation every time Meralonne’s hands had finally touched bark; he expected no different, and was not therefore disappointed. The mage’s hands stiffened, his fingers trembling in place. He whispered a word, and if the word did not carry to the bard’s ears over the clash of blade against armored root, what lay beneath the utterance did.

In the clearing made by a hunger that could never be satisfied, even if the whole forest should be devoured, light broke the cover of night, falling in sharp, defined spokes. Meralonne APhaniel invoked the ancient magics of Summer as if Summer would never again be seen in this world. He turned his face away from the bard’s view; he could do this much, but not more, for the tree’s sudden scream of fury meant the safety of distant kinship was at an end.

Winter rose as roots thinned and sharpened at the ankles of the mage; he did not even gesture before they fell away, melting beneath the sudden heat of Summer, the scorching light of a different desert. He flinched as the tree’s screams transcended rage and fury for the territory of pain. Had Kallandras not now been fighting for his life, he might have sung—but his song did not reach the heart of the tree the way the Serra Diora’s once had; he had tried.

Summer flames burned; bark melted, roots withered. Only bark and root; the flames did not catch cloth or hair, and where it touched the edge of growth not yet devoured in the spread of this single tree’s roots, it burned nothing—but the leaves of undergrowth leaned inward toward that light, and the flats of those leaves brightened in color, the small branches lengthening. These lesser plants lacked the sentience of the Winter tree; they could not and did not speak. Nothing in their welcome dimmed the horror and the loss of the single tree’s death, and even as the tree withered, small shoots of pale, pale green could be seen in the troughs and furrows made by the passage of Winter roots.

Meralonne’s hands fell to his sides; what remained of the tree was now silent. It would crumble if Kallandras touched it; it would crumble if anything did. Anything, or anyone, but Meralonne APhaniel.

“Come.” He bowed head a moment; his forehead grazed what remained of standing ash. “We are almost done.”

His voice was the voice of the desert.

* * *

Meralonne was wrong. The quiet, grim march across the slender and invisible border of the Terrean came to an abrupt end in an unexpected way. They heard the sounds of fighting. Kallandras spoke softly, as was his wont, and the mage had become so taciturn in his work that words were harder to pry from him than blood. Even in their combat against these unnatural trees—and there had been many, each dissolved, in the end, by the harshest of Summer light—their conversation had dwindled to the wordless syllabus of blades, air, and fire.

Not so the combatant in the distance: he

roared

. It was a harsh, almost guttural cry, in a language unknown—but not unfamiliar—to Kallandras. The bard’s blades rose in an instant, and he forced them down as he glanced at his companion; Meralonne’s robes shifted as he nodded, becoming a fine, heavy mesh of something that might have been chain, had chain been light and magical. Significantly to Kallandras, he did not draw his sword; he gestured briefly, and wind played in the sweeping fall of platinum hair as he turned toward that roar and began to walk.

His stride was supple and wide; Kallandras kept pace with some difficulty. But he was grateful in some fashion for the interruption. The mage’s gaze was now brighter, the line of his shoulders, straighter. He took the lead; Kallandras was content to follow. If he did not relish the possibility of combat, he prepared for it; it had become a fact of life, as necessary as breath if one wished to continue to breathe.

Through the night forest, in the light surrendered by moon in a clear, dark sky, they at last approached a clearing similar in shape and size to one they had just left. Kallandras could see the edge of living foliage as it circled fallen branches and the husks of great trunks. But there was no stillness, no silence, in its center. Each time Kallandras and Meralonne had approached such a clearing, there had been a tree of ice awaiting their arrival; what stood in this dead clearing barely resembled a tree, it was so misshapen. The earth was overturned where roots had broken free of its confinement; they rose like armored tentacles, slashing and stabbing at the only thing present that was not likewise bound in a similar fashion.

He was as tall as Meralonne APhaniel, if not as fine-boned, and his hair was ebon to the mage’s platinum; his skin looked all of red in the light cast by the shield and sword he bore. Where Meralonne had touched the tree with his exposed palms, the

Kialli

did not; he slashed at its trunk. Fire gouted from the edge of blade as roots writhed and coiled. In one wide sweep of sword, they fell, but they were almost instantly replaced.

Kallandras was silent; Meralonne, silent as well, although the mage exhaled sharply. The bard glanced at him, seeking direction; in response, the mage drew sword for the first time in this long march of days. It was blue, its glow harsher than the red illumination of

Kialli

sword.

Invoke the Summer

, Kallandras thought; he gave no breath to the words—he had no time. Meralonne APhaniel leaped above the circumference traced by dead foliage; he leaped above the easy reach of roots coiled like armored snakes. The sword crossed his chest as he gestured with both arms. Blue light cut a trail across the bard’s vision. When it cleared, Meralonne was a yard above the ground; roots flew where they sought to attack him as he cut his way toward the heart of the moving trunk.

Kallandras whispered a benediction to air and it came; he leaped, as Meralonne had done, landing at the same height. He did not attempt to make his way to the heart of the trunk; instead he fought a rearguard action. He had no desire to strike the killing blow; if APhaniel or the

Kialli

now engaged in combat brought a ferocity of exultation to their battles, Kallandras did not. Nor had he ever. Necessity was his only guide.

Not so, these two: the

Kialli,

seeing the direction Meralonne took, roared again. Kallandras almost froze at what he heard in the demon’s voice. Had he, he would have died, and if he had no desire to claim a kill as his own, he had no desire to die in this forsaken place. He leaped beyond the reach of both

Kialli

blade and piercing root, changing his trajectory in the air as he did. If the tree in this form seemed a nightmare of bestiality, it was not without its cunning.

He did not choose to alight; because he rode the currents of the wind, that choice was his to make. Air was caprice personified, but without rage, it had little malice. He landed, cut roots and parried them before vaulting into air again, losing some part of his boots in the process. Although at each stage of this isolated search he’d been forced to defend himself against the oppressive hunger of trees such as this, he had yet to see the earth erupt so violently.

Because it had, he could only peripherally observe what occurred beyond his immediate fight for survival—but the sky flashed red and blue and white and the song of swords clashing implied a sword-dance. He wanted to turn, to watch; he wanted to survive. The

Kialli

did not roar again, and Meralonne did not speak; the clashing glow of colored light grew faster, the brightness more intense, and then, in the space of a breath and a heartbeat, both were gone, and the roots that had gathered in such number stiffened, stilled.

Sheathing the weapons that had been Meralonne APhaniel’s gift, Kallandras whispered his thanks to the wind and released it; he stepped upon upturned earth, between the dying roots. As if it had been struck by bladed lightning, smoke rose from the tree’s trunk; bark hung in tatters, like flayed skin. Where blades had cut wood, gashes remained, but no sap flowed from the wounds.

Meralonne APhaniel’s sword was no longer in his hand. He turned to the armed

Kialli

. “This is not your task,” he said, his voice clear and resonant.

“No more is it yours, Illaraphaniel, and yet you are here.” The smile he offered was slight and sharp; it was framed by small scratches, which surprised Kallandras. So, too, his cape, although his armor was clean and untouched. He sheathed sword in the way the mage did; it faded from view, the red, red light dimming. He surrendered shield in the same way.

“Were it not for your presence,” the mage replied, “there would have been no fight.”

At this, the demon laughed. It was the first laughter that Kallandras had heard in almost a week. “And are you now so old and so enfeebled that you decry the necessity of combat? You?”

Meralonne gestured; his sword returned to his hand.

The demon, however, remained unarmed. “You will need your sword in the time to come.” Mirth ebbed from his voice as he spoke, light from APhaniel’s hand as the blade once again vanished.

“Why did you come, Anduvin?”

The

Kialli

was silent for a long moment, studying Meralonne; at last, he shrugged. “I wished to see for myself the damage done. A road existed here, where no roads travel that were not made by mortals; it was fashioned by the roots of the Winter trees. I do not know what treachery allowed those seedlings to leave their master—but they are gone now.”