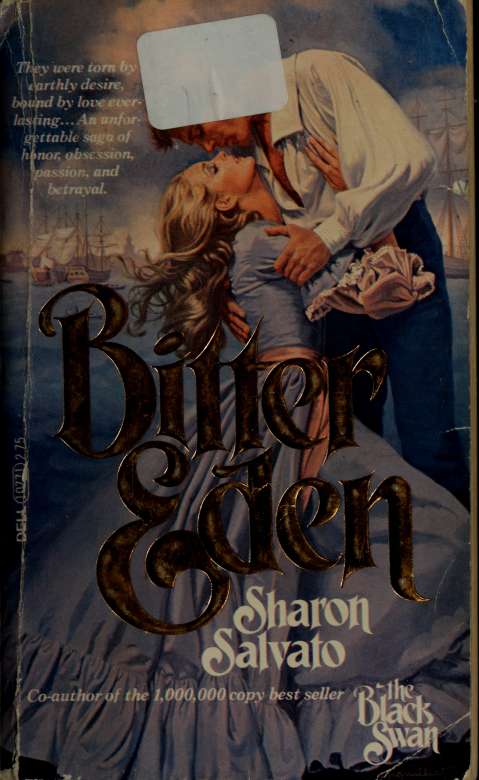

Bitter Eden

Authors: Sharon Anne Salvato

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

-

BOOK I

Chapter 1

The fertile rolling land of the Kent countryside was covered with a slick wet film of ice during the harsh English winter of 1829. In place of the heavily laden fruit orchards and the grand green arbors of the hop vines, there was a look of barrenness broken only by the pathetic tops of winter turnips planted along the ridges where the hops had been.

At Gardenhill House, Peter Berean alone was left outside. He finished cleaning the farm implements and replaced them in the barn. Beating his hands together, he walked slowly across the stable yard. Across his shoulders cold moisture had seeped into the fabric of his coat, leaving dark wet patches. He stopped, and tucked his gloved hands protectively against the warmth of his ribs. He stared with longing at the impressive half-timbered manor house. The timbers were bent and twisted by time; oak mellowed with age until it blended in regal antiquity with the stuccoing. Diamond-shaped lead-paned windows reflected gray winter light. Sighing, Peter turned away, looking up into the threatening, leaden sky. It would

be dark within the hour and the weather was worsening.

From the protection of the house, a woman stepped into the yard. His wife. She stood, hands on hips, watching him. He didn't see her.

Peter stared up into the boiling, thunderous clouds, seeking guidance. He didn't know what was right. He felt the hurt and desperation of the Kentish peasants sharply, and with all his compassionate nature he wanted to help, but he didn't know what was right. And who was there to tell him in these troubled times?

He rubbed the back of his hand across his mouth. He had seen Nate Wheeler's rotting corpse hanging from the gibbet at the crossroads to Seven Oaks this afternoon. The vision, still too clear in his mind, had the power to bring stinging bile back into his throat. He silently asked the threatening sky, Had that been right?

Nate had been a brawling, angry man when he died, but Peter could remember a time not long ago when Nate had been cheerful, a smiling man who wanted only a mug of ale and a good laugh before going home to his wife and seven children. That had been before the common pasture and hunting grounds had been closed off and put under the control of the squires and the wealthy. It had been before machinery had taken from Nate's wife her profitable cottage industry; before Nate had no longer been able to earn enough to feed his children; and before war and weather and progress and taxes had changed England.

Peter shuddered. He was cold and more than a little afraid of the future. It wasn't difficult for him to superimpose his own features onto the purpled, bloated face of the dead Nate Wheeler. Courage was elusive when he imagined his loved ones riding the cart to

town and passing the decomposing remains of his own hanged body.

But he knew he would ride to the laborers' meeting tonight, because he had to. He was an honorable man, not in the least sympathetic to politics or the machinations of progress. He saw only the pain and the hunger and the fear in men he knew, men he hired to work his own lands, and it was to that Peter Berean responded. Tonight, once again, he'd become one of the illegal night riders who took orders from the phantom leader, Captain Swing.

Rosalind Berean watched her young husband, his profile rigid and strong, look unblinking into the merciless opaque sky. Her own jaw was clenched so tight it hurt as she willed him to turn from his thoughts and look at her. He wouldn't. She knew he wouldn't, for she knew what filled his mind as well as he did, and she hated him for it. She hurried across the courtyard. He jumped at the sound of her sharp, angry voice; then, as always, his dark brown eyes softened at the sight of her.

For a moment Rosalind allowed herself to be warmed by him. Her eyes began to water and her lips trembled with the need to smile. It was so easy to trust him. And so horribly frightening. She looked away from him, her eyes set on the bleak winter landscape. She'd conquer her involuntary reactions to that gentle loving look of his, for it meant nothing when all was said and done. For his damnable peasant laborers he'd risk everything—his home, his life. And what did he give to her? Long lonely hours in empty, worry-filled nights. He knew how much she dreaded even the thought of men like the Swing men. He knew what hideous memories they brought back to her. But did he consider her feelings? Did he ever once re-

JO Sharon Salvato

member the terror or humiliation she had suffered by hands such as theirs when she was no more than a child and forced to work in her father s tavern?

"I could freeze to death and you'd never care!" she said. Her voice was shrill. "I'm sick of it, Peter/' She looked at him then, and saw puzzlement flash across his face then disappear as he reached for her. She pulled away from him as he tried to enfold her more deeply in the warmth of her scarf. Fighting both herself and him, she said, "There's an end to my patience, and you've passed it. I won't have you treating me as you have been! I won't! I needn't stand for it. I left all that when I left my father to marry you. Those men are dirty! They're . . . they're horrible . . . horrible . . . things."

Her words now made sense. Fear and anger knotted inside him. He didn't know how to protect her and still do what he believed was right. He understood her hatred of the peasant men. He was aware of her pain. How could he not be? How could any man who loved a woman be unaware of what other men had done to her? He knew all these things, and the knowledge twisted and turned inside him, but he couldn't stop aiding the Swing men, not when thousands of Englishmen walked the roads hungry and unable to find work, unable to find rest or solace. One by one they would fall victim to the unreasonable justice of England's Bloody Code and die for their hunger as Nate Wheeler had. Peter couldn't be a passive audience. Why couldn't Rosalind see that? Why couldn't she take pity, knowing that the things these men suffered she'd never suffer, because he would keep her safe.

Then, as he looked at her, a great weariness crept over him. Nothing was clear to him. Sometimes he thought that it was he who needed protection. He was

like any other man, wanting his wife, her love, his home.

Steamy puffs of her breath dotted the air between them. "My God, when will you learn to mind your own business?" she said. "It's not as though you haven't enough here to keep you busy."

His eyebrows, so startlingly black beneath his thatch of pale blond hair, were touched with a whitening of frost. His dark brown eyes were full of life and pain, and even now held an unquenchable warmth. "What would you have me do, Rosalind?" he asked softly. 'The farm workers are starving."

"And what of me? There is more than one way to starve. Remember that, Peter. Remember who you married."

"I never Torget that," he said. "Rosalind, be patient, please. Everything will be different soon. There won't be any night rides then."

She raised her chin. "Oh, yes, everything will be different, and perhaps sooner than you expect. I'm tired of promises, Peter, and I'm tired to death of being put second to those dirty, smelling peasants. They're not worthy of your help or anyone else's. I hope they all die! Every one of them! Even you!" He reached for her. "Don't touch me! Stay away from those . . . those ... I swear to you, Peter, things will be different between us in a way you won't like. I'll never be dirtied by that scum again!" She ran from him, disappearing inside the house with a flurry of skirts and wind-whipped scarves.

Peter listened to the door close; then, head down, he followed, his anger rising. Frank had been talking to her again, he knew it. As he walked to the house, a vision of his older brother's florid, self-satisfied face mocked him. Frank had fed Rosalind's fears. He

would do anything he could to make Peter give up his fight for the peasants.

The wind caught the door as Peter entered the house, slamming it shut with a ferocity that shook the leaded windows. Seven startled members of the Be-rean family looked up from their activities and then became attentive to the grim angry look of him.

"Frank," he said, and without preamble strode to his brother, his fists clenched. "You and I have something to settle between us right now."

Frank, secure in the presence of the rest of the family, smirked. "I suppose you're looking for a brawl."

Rosalind whirled from the glowing heat of the hearth fire. "You and Frank?"

"Yes, Frank and me. Don't tell me he wasn't filling your head with his talk before you came outside."

"What I said to you outside has nothing to do with Frank. He's right about you. You are a thoughtless, irresponsible child! You're going to bring trouble and humiliation to the whole family. You've no right to be with those horrible Swing men. You're not of them. You've nothing to do with them. If they didn't drink their wages they'd have money for their families. They don't want help or work!"

"Is that what you've been telling her?" Peter shouted at his brother. "That those men . . . what the hell is it, Frank? Can't you say what you have to say to my face? Why frighten my wife?"

Frank slowly folded his newspaper and looked with pained tolerance at his younger brother. "As the eldest in the family, Peter, I feel it is my duty to correct you when you're wrong. I have never hidden my views from you, and I have no need to use your wife. You're a bloody fool and always have been. You're playing a child's hero in a game you don't understand, and sooner or later we'll all pay the price of your stupid

heroics. Riots! Demonstrations of need!" Frank snorted. "Those peasants don't want your help and don't need it. They have the dole to see them through. Let Albert Foxe tend to their ills. It's his job."

"If the magistrates did their jobs fairly there wouldn't be such a problem."

Frank shrugged. "Whatever. In any case it is not your problem."

Peter hit his shoulder, spinning Frank to look at him. "It is, damn it! It's the business of all of us. Especially us. We're educated. That gives us an obligation. If we who have learned and are supposed to be wiser don't take a hand, it'll come to a bloodv confrontation between the laborers, landholders, and government. Would you prefer that? Is that what you would see happen to preserve vour own precious skin?"

"Oh, blessed heaven, he's going to give another speech," Rosalind groaned.

Frank ignored her. He raised his arm, met Peter's eye, and moved sharply to slam his paper down on the table. His heavy face was marked with loathing. "You damned arrogant cock! Where in the hell did you get the idea you could cure the ills of the world? Obligation! Damn obligation. Your obligation is to this family, this hop garden. Nowhere else! No bloody where else!" Emboldened, Frank advanced on his brother, his forefinger pointing at Peter's chest. "Get it into that thick stupid skull of yours that I won't tolerate your nonsense. If you weren't my brother I'd turn you in for the damned traitor that you are! We have a reputation to uphold, and by damn we'll do it! We don't have a part in the doings of a bunch of filthy, ale-swilling laborers. Tell the bastards to stop drinking their wages, and they'll have bread on their tables."

Peter slapped Frank's hand away. "You son of a bitch," he said in a low, throaty whisper. "You

damned, greedy, self-serving son of a bitch. What you mean is that Frank Berean wants to be somebody in this parish. Frank Berean wants to rub asses with the people who count, and anything to be sacrificed to that is worth it."

"You're damned right! In this world you either go up the ladder or you go down. I'm going up. And 111 look out for me and mine, because if I don't no one else will."

Peter's hands clenched into fists again. Rosalind laughed and walked over to him. "Oh, please! No brutal demonstrations in this happy family setting.". She put her hands on his arms. "You should listen to Frank, Peter . . . except that he is wrong about one thing. When a man doesn't choose to look after what is his own, there is usually someone around who is very willing to take his place." Mockinglv coy, she ran her finger along his jaw, then went upstairs to their bedroom.

Peter glared at Frank, glanced hastily after his wife; then, defeated, his eyes sought and found the understanding eyes of his younger brother Stephen. But before Peter could speak, James Berean walked into the room, assessed the situation, and gestured to his son. "Go up to her, Peter."

Frank said, "Unless he has something better to offer her than more of his shenanigans, it'll do him no good to . . ."

"You'll disrupt this family no more this evening!" James said. "Go up to her, Peter. And you, Frank, go soothe your own wife. Look at her. She's as upset by this as Rosalind is by Peter." He pointed to Anna Berean sitting quiet and huddled in a corner of the sofa. Still agitated, and wanting to reestablish order in his home, James ordered Stephen to check on the brew-house, then began to pace the room.

_

Bitter Eden 15

Meg Berean moved to her husband's side. They looked at each other, but neither had anything to say. Meg smiled weakly at James, then went to gather mop and bucket.

Cleaning up the muddy tracks Peter's boots had made on the floor, Meg clucked over his carelessness and worried about him. He was thoughtless in small ways, but she knew this son was a man she could always count on to be kind where it counted most. It wasn't her eldest, Frank, who looked after his father. It was Peter who did his own work and took on a great portion of James's labors as well.

James settled down in his chair, his eyes closed, pretending to nap. From above he could hear Rosalind's angry voice and Peter's deep one. There was nothing so peace-shattering in a house as an unsatisfied wife, or two sons who for all their lives would never live in harmony. "Meg, my love," he said with false joviality. "Do you suppose this old man could be fed soon?"

"You can indeed. You wash up and I'll have supper laid before you're finished."

"Wash up, she says! Just like the old days when we came filthy from the fields. Ah, Frank, your mother will never change."

"It was just a manner of speaking," Meg sniffed. She added in a haughty voice, just as Stephen returned, "Dinner is served."