Bette and Joan The Divine Feud (16 page)

9

The War Years

"Stars are not important. You

have to be General MacArthur

to achieve fame."

—JOAN CRAWFORD

"It should be our duties as

American wives, sweethearts

and mothers, to unite to avoid

any lowering of American

morals. The length of skirts or

the color of lipstick may be of

great importance to some, but

these difficult times should put

an end to such foolishness."

—BETTE DAVIS

O

n the afternoon of December 7, 1941, while the Japanese were bombing Pearl Harbor, Joan Crawford was on her hands and knees scrubbing the kitchen floors of her home in Brentwood, Los Angeles. Bette Davis was in bed, at Glendale, recovering from the flu. And Lana Turner was at her house off Sunset Boulevard, preparing for one of her Sunday-afternoon record hops. When told three hours later that Pearl Harbor had been destroyed, Lana reportedly answered, "Who's Pearl Harbor?" (A quote also ascribed to Betty Hutton and Gracie Allen.)

Six months before Hollywood reacted to the war in "a burst of patriotic enthusiasm and economic shrewdness," Joan Crawford had rallied to the cause. In July 1941 the New York

Times

reported that she was the chairwoman of a drive to raise money to buy cots for five thousand children in air-raid stations in London. That Christmas she knitted socks and scarves for British soldiers, and one afternoon she stood on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Fifty-second Street, "rattling a tin-can for contributions and selling autographs for a quarter." She raised something like four hundred dollars, said the

Times.

When Bette Davis heard the news of Pearl Harbor, she said: "What's the use of going on acting when your country is at war? But then I felt

that's

what the enemy wanted—to destroy and paralyze America. So I decided to keep on working."

By October 1942 twenty-seven hundred people, or 12 percent of the Hollywood movie industry, were in the armed forces. Those remaining were put to work, producing the three hundred feature films and countless cartoons, documentaries, and short subjects designed to entertain the public and spur the fighting men on to victory. At Burbank, within days of the war declaration, Jack Warner was on the phone to the White House, discussing his studio's planned contribution, and his honorary commission in the Army. He asked President Roosevelt to start him out as a general, but settled for lieutenant colonel instead. "He insisted we call him 'Colonel,'" said Ann Sheridan. "Then the old fart had his officer's uniform tailored by the studio's wardrobe department." At Twentieth-Century Fox, Major Darryl Zanuck closed his office, put on his sunglasses, and left for Europe, where the war action was. He would personally supervise and edit the combat footage, from his headquarters suite at Claridge's Hotel in London. Major John Huston was at Warner's, finishing up

Across the Pacific

with Humphrey Bogart, when he was called to active duty. After tying up Bogart in a chair, surrounded by Japanese soldiers holding machine guns, Huston left a note for Jack Warner: "Jack, I'm on my way. I'm in the army. Bogart will know how to get out."

Of the major studios, M-G-M was hardest hit by the induction of male talent. Among the stars who enlisted or were drafted were Clark Gable, Jimmy Stewart, Mickey Rooney, and Robert Taylor, leaving sixty-one-year-old Wallace Beery and five-year-old Butch Jenkins to defend the Metro gates. Another actor left at M-G-M was German-born Conrad Veidt, on constant call to play Gestapo heavies; and actor Helmut Dantine was voted the best-looking Nazi. "There were ugly Nazis too, like Otto Preminger and Alexander Grenach. They were all Jewish," said director Marcel Ophuls. At Twentieth-Century Fox, Henry Fonda left his wife and two kids to join the Navy, and Tyrone Power said goodbye to "his wife and a male lover" to join the Marines. At Republic, a stalwart John Wayne was excused from military service, due to family commitments and a badly damaged shoulder; while over at Warner's, many of their top male stars chose to fight the war from within the safety of the Burbank soundstages. Errol Flynn, George Brent, and Cary Grant were British subjects and immune from the U.S. draft. Humphrey Bogart had a hearing disability and John Garfield had flat feet. That left Ronald Reagan, who was a captain in the Air Corps Reserves. When he was called to active duty, he "bravely kissed Janie [Wyman] and button-nose [daughter Maureen] goodbye" and left for Fort Bragg, forty miles from L.A. After basic training, Captain Reagan's eyesight was deemed poor. "If we sent you overseas, you'd shoot a general," the examining doctor said. "Yes, and you'd miss him," his assistant concurred. So Reagan was assigned to a squadron that made training films, in Los Angeles, not far from the M-G-M studios, where his group, including Alan Ladd, were known to each other as the Culver City Commandos.

In May 1942, confident that the war would soon be over, Bette Davis gave the first "Victory Party," at Mogambo's, a surprise birthday celebration for her husband, Farney. For "the blackout theme," the club was in total darkness and Bette supplied guests with their own flashlight. Special victory cocktails—"3 dots of rum and a dash of Coke"—were served, and each guest got to wear an armed-forces service hat of his or her choice.

That winter, as the war in Europe and the Pacific escalated, the stars embraced a new austerity program. There would be no parade, Christmas trees, or Santas on Hollywood Boulevard that year. Bette Davis, wearing a severe hairdo and a black dress, appeared in a movie short with two fictitious kids, Billy and Ginny, gently explaining to them why they would not be receiving a baseball bat or a bike that Christmas. She was giving the money instead to the Red Cross, so they could buy food and medicine for their father, "fighting somewhere far, far away."

With their men at war, real and pretended, it was up to the women of Hollywood, and their children, to project images of strength and sacrifice to the millions of other war wives, mothers, and children across America. Clothing was scarce or rationed, so Loretta Young was photographed giving her two sons' outgrown T-shirts, jeans, and underwear to Rosalind Russell (for her son, Lance). At home, Bette Davis had to make do with a two-party line, sharing her phone with a lady in Glendale. ("Of course she hasn't a

clue

as to who

I

am," said Bette. "Whenever she tries to listen in to my calls, I deliberately talk dirty. That usually makes her hang up.") Lucille Ball bought a tractor and planted victory corn in the Valley. The four Crosby boys organized a paper-string-and-rubber drive in their Sherman Oaks neighborhood; while Joan Bennett and Paulette Goddard posed shopping with food coupons at their local supermarket in Beverly Hills.

The severe gas rationing affected Hollywood too. Many two-car families now made do with one, and some stars went to work on bicycles. Bette Davis jaunted around Los Angeles, briefly, in a horse and carriage; while Joan Crawford made her shopping rounds on a special motorbike, fitted with bucket seats on both sides, so she could bring the children with her when she went to market. Christina, however, was a little testy when it came to coping with the shortage of hired help. "Our maid and butler left us, to work in a defense plant," said Joan. "Christina was asking everyone to wait on her. 'Please get me this or that,' she would order. I explained to her we had no help and that she had to wait on herself." Christina adjusted, fast. Standing on a chair by the kitchen sink, she learned how to dry the dishes. She also helped at dusting, wearing special white gloves and an apron embroidered with the words "I love Mommy, God and America." In that order.

"The Nazis won't quit, the Japs

won't quit, and you won't quit either."

—JIMMY CAGNEY

DURING A WAR BOND DRIVE

At President Roosevelt's request, many stars were recruited to donate their time, talent, and charisma to selling war bonds. When called by the White House, Louis B. Mayer gave up his publicity chief, Howard Strickling, for the War Bond Drive. Strickling organized the Hollywood Victory Caravan, a special train carrying stars across America, promoting the sale of kisses and bonds for defense funds. Among the passengers who embarked on the three-week tour (performing in a three-hour show in eighteen major cities) were Cary Grant, Jimmy Cagney, Merle Oberon, Claudette Colbert, Joan Blondell, Olivia de Havilland, Groucho and Harpo Marx, Betty Hutton, Judy Garland, and Fred Astaire. The tour kicked off in Boston, went on to Washington, and eighteen days later arrived in Los Angeles. "Our quota was $500 million, but we sold over one billion," said an exhausted Greer Garson. The MC of the show, Bob Hope, said this was his first patriotic tour, and he was seriously considering going out on another.

There were other stars and talents in Hollywood who donated their time to entertaining the armed forces, without publicity or comfort. Joan Blondell took her own troupe and performed at 126 Army bases; Gary Cooper sang and danced in the South Pacific; John Garfield went to North Africa and Sicily; and Ann Sheridan went on a grueling four-month tour of India, China, and Burma. "Jack Warner was big on USO tours," said Sheridan, "but not too big. He threatened to suspend me when I didn't get back on time from Burma. I said, 'Go ahead.' He kept trying to get wires and letters through to me, but they'd arrive three weeks later. We didn't know where we were going until we opened our special orders. It was rough! Sleeping on the floors of planes, and living on K-rations. And the heat! I lost sixteen pounds. But I wouldn't have missed it for anything in the world."

Neither Bette Davis nor Joan Crawford left the mainland during the course of the war, but their volunteer efforts were noticeable. Joan made the earliest and grandest gesture. She donated her entire $128,000 salary from

They All Kissed the Bride

to the Red Cross, the organization that had found the body of "my darling Carole Lombard." Bette Davis appeared on the Armed Forces Network radio show in Los Angeles and traveled to army camps and hospitals in California, but no farther than a radius of two hundred miles from Burbank. "Jack Warner wouldn't release Bette for an extended tour," said Joan Blondell. "She was his top moneymaker. It was all right for the peons like Annie [Sheridan] and I to get shot at, but he wouldn't allow Bette to be anywhere near the war action."

In January 1943 Crawford announced she was disbanding her fan club. "It seemed to me more important things were facing all of us," she said. In February she announced she had founded a group called America's Women's Volunteer Services. The group took care of children whose mothers worked in the defense factories around Los Angeles. In April she was voted the chairman of the War Dog Fund, raising money to train dogs for the armed forces.

Not to be outdone, Bette joined the Hollywood Victory Committee. But she wasn't too happy with this group. "They gave permission for actors to appear in camp shows," she said, "and the egos and politics abounded." She really wanted to be the boss of her own group. One day John Garfield came to her in the greenroom at Warner's. He had been thinking about the thousands of servicemen who were passing through Hollywood without seeing any movie stars and Bette instantly agreed something should be done about that. So the two found a building off Sunset Boulevard that looked like two New England barns thrown together. They recruited carpenters, designers, all of the guilds to donate their time. In three weeks the Hollywood Canteen was ready. On opening night Bette had to crawl through a window to get in. They had more stars than the GIs could count: Marlene Dietrich, Gary Cooper, Rita Hayworth. "Everyone agreed this was the greatest gift we could give the boys," said cofounder Davis.

Not everyone. Joan Crawford had her own plans to entertain the servicemen. Inspired by the meet-a-star-over-donuts-and-coffee theme of the Canteen, she decided to throw open her house to the boys for Sunday-afternoon picnics. She set up a barbecue and tables on her front lawn and persuaded teenagers Judy Garland and Shirley Temple to act as junior hostesses and serve hot dogs and soft drinks to the soldiers and sailors. But during the first picnic some of the boys got a little rowdy. One of them spiked the punch, and at evening's end he and a buddy were seen standing beside Joan Crawford's pool, teaching her two-year-old son, Christopher, how to "piss clear across the creek."

Joan's Sunday picnics were canceled after that. The star explained that with her Japanese gardener interned in a concentration camp, she was having her front lawn plowed and planted for a victory garden, "with fourteen different kinds of vegetables, including carrots and radishes."

Queen Bette

"Bette has played so many

meanies on the screen that she

has developed a swaggering

insolent walk to fit the parts she

plays. Let's hope she doesn't

adopt the walk in real life. Don't

mince. Don't stride like a man."

—ADVICE FROM MADAME

SYLVIA IN

PHOTOPLAY

"Show me a great actor, and I'll

show you a lousy husband; show

me a great actress, and you've

seen the devil."

—W. C. FIELDS

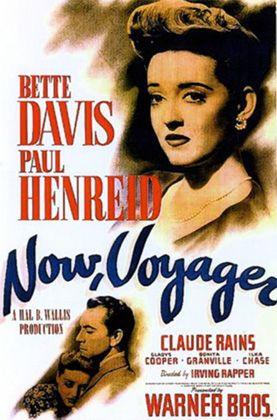

Professionally, no other actress in Hollywood could match the accomplishments of Bette Davis during the early 1940s. These were her golden years, when she appeared in one dazzling success after another—including

The Letter, The Little Foxes, Now Voyager, The Man Who Came to Dinner,

and

Mr. Skeffington.

Among the numerous awards and citations she received was one dubious honor from the Harvard

Lampoon.

In one of their annual polls, the Harvard students named Miriam Hopkins as "the least desirable company on a desert isle." Joan Crawford, along with George Brent, was deemed to be "most qualified for a pension," and Bette Davis was awarded a special citation for "having suffered the worst ordeal in

All This and Heaven Too."

According to many at Warner Bros., Bette did not suffer alone during the making of her pictures. "She put everyone through hell, including some of the toughest stars on the lot," said a co-worker.

In 1934 Bette had made

Jimmy the Gent

with James Cagney. He was the star of the picture, but Bette couldn't stand his haircut. "It's cut too close to the scalp and gives me the creeps," she said, refusing to pose for publicity stills with the actor. "Jack Warner was giving her a hard time at the time," Cagney said gallantly in his memoirs, "so she took it out on all of us."

In 1941 Cagney and Davis were reunited for

The Bride Came C.O.D.

This was her first location picture (similar to Crawford, the sun dared to make Bette squint), shot in Arizona. During filming, the actress found some of her lines were changed. She couldn't complain to the producer, because he was Cagney's brother, William. "I'm so sorry I never thought to fix it so my

sister

could produce pictures," said Bette to Jimmy. "Perhaps if I did I could change scripts

too."

Cutting her lines, and his own, Cagney "endured many silences from Bette." She, however, derived "enormous fun and satisfaction" when she got to throw a bucket of water in Jimmy's face, missing her mark twice, which meant the dunking scene had to be repeated three times.

"Nobody but a mother could have loved Bette Davis at the height of her career," said her

Juarez

costar, Brian Aherne. "Even when I was carrying a gun, she scared the be-jesus out of me," said Humphrey Bogart, her costar in

The Petrified Forest.

"It could be marvellous to work with Bette," a source told author Larry Carr, "and it could be absolutely hell. Everything depended on her mood at the time. When she was in a good mood, the cast and the crew would relax and filming went smoothly. But when she started her famous tirades—watch out! At such times her behavior was so counterproductive that the picture and everyone with it suffered accordingly. She seemed to thrive on conflict, to want to create turmoil, and when that sort of thing occurred, she was the greatest bitch I've ever known."

Errol Flynn was obviously not an actor Bette admired. She said loud and clear that she refused to work with him in

Gone with the Wind.

For spite, Jack Warner subsequently put her with Flynn in two pictures. The first of these was

The Sisters,

with Flynn top-billed. "Why in heaven's name with a title like that is he first?" Bette yelled at Warner, who replied, "Because

he

is prettier."

"He was the most beautiful man God ever created," said Ann Sheridan, "and a charmer." "I like my whiskey old and my women young," said Flynn. "Errol was my shining knight," said his costar Olivia de Havilland. "Mine too," said her sister, Joan Fontaine. "Imagine anyone calling Errol Flynn a Nazi," said Myrna Loy. "God! He was never sober long enough." "I only know one thing," said Ida Lupino, referring to Flynn's statutory rape trial, "Errol never raped any girl. They all raped him."

On the set of

The Sisters,

Bette Davis complained frequently about the number of "unauthorized females" who stood on the sidelines ogling Flynn. If she suspected that a continuity girl had her eyes more on Errol than on her clipboard, she would tell the director, then walk off the set.

Flynn was never serious about his craft, said Bette. "He went fishing and fucking, and paid no attention to his talent," Viveca Lindfors stated. "There is no thrill like making a dishonest buck," Flynn agreed.

In 1939 he was cast with Bette once more in

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex.

She wanted Laurence Olivier as Lord Essex, but without Flynn, Jack Warner told her, the film would not be made. Bette relented, then proceeded to supervise the rewriting of the script and overrode the director, Michael Curtiz, on her costumes. Before the picture began shooting, the title underwent some changes. To capitalize on Errol Flynn's bigger draw at the box office, it became

The Knight and the Lady;

then

Essex and Elizabeth.

"You

cannot

give second billing to the Queen of England—or to

me,"

Bette screamed at Jack Warner. "Either change the title or I'm walking out."

In her love scenes with Errol Flynn, the idol of millions, Bette closed her eyes and imagined he was Laurence Olivier. Flynn had no complaints. "She's a far better actress than I could ever hope to be as an actor, but physically she's not my type," he said. Davis said he almost propositioned her, "but was afraid I would laugh at him. 'You're so right,' I told him."

As Queen Elizabeth, Bette busted his ass in the royal-court scenes, said Flynn. He was required to walk repeatedly down "a seemingly endless carpet" to face Davis, only to find her stand-in on the throne. "When she finally did mount the throne," said Michael Freedland, "she greeted him with a powerful slap across the cheek—a slap made all the harder by the large rings on her fingers." Flynn, who had once suffered a double mastoid operation, was worried that several blows could deafen, even kill him. He went to see Davis privately, in her dressing room. He asked her to go easy in these scenes. She scorned the idea of holding anything back. "A slap has to be a slap," she told the fearful Flynn, whose reaction, he said, was to throw up outside her door.

Queen Bette and leading man, Errol Flynn

"Bette is really unable to conceal

for any great length of time that

she considers herself God's

greatest gift to screen acting.

She believes that to be a simple

fact of life. Oh, she can be

disarmingly candid and funny

about herself for a short while—

sometimes even modest. But

soon that overwhelming

ego of hers starts rising

to the surface again."

—LARRY CARR,

THOSE FABULOUS FACES

On the set of

Elizabeth and Essex,

among Queen Bette's usual attendants was a boy whose sole duty was to follow the actress, holding up an ashtray lest she spill ashes on her expensive costumes. When filming was completed, for his faithful, silent service Bette regally gifted the lad with three coins—not gold but silver—a quarter, a dime, and a nickel.

But Bette wasn't cheap, said a source who knew her and Crawford. "If anyone came to either with financial trouble," he said, "Bette and Joan were always the first to reach into their handbags for their checkbook. Furthermore, they would refuse repayment, no matter how large the sum."

Being a star made it difficult at times for Davis to relate to mere mortals. "It was always the small, human things she had trouble with," said a Warner's publicist. "Like good morning or hello or thank you. She was also very moody. Some days she would be very chatty; then others she could wither you with a glance."

One Christmas Eve, Bette arrived at the Warner's mailroom carrying a twenty-pound turkey on a platter. It had been cooked and carved personally by the star. "Merry Christmas, boys," she said, leaving the bird to be equally distributed by the staff.

"

END THE WAR! SEND BETTE DAVIS TO THE FRONT

" was a piece of graffiti scrawled across the north rear wall of the studio lot. When the head of maintenance was called by publicity head Bob Taplinger to have the slogan removed before Davis saw it, he replied, "But she's already seen it. She called this morning and wanted to know why it wasn't put closer to the main gates."

"Bette has a lot of mannerisms.

I wanted her to be simple and

dignified, and not resort to a lot

of gestures and accentuated

speech and tricks that are just

plain bad."

—WILLIAM WYLER

As mentioned, Davis, like Crawford, was seldom forgetful of old slights and injuries. When producer Samuel Goldwyn asked her to play Regina Giddens in

The Little Foxes,

she delayed giving him an answer. It was Goldwyn, in 1929, who had vetoed her first screen test, so for

The Little Foxes

she asked the producer to cough up $385,000 for her loan-out services, "all of which I kept from Jack Warner," the star said happily.

She was attracted to the character of Regina, the cold and greedy matriarch, because "she has the courage to do the brutal things I've always wanted to do and couldn't." Another draw for Bette was the chance to work once more with her favorite director, William Wyler. Unfortunately for all, this would be their last collaboration. They fought viciously throughout the entire filming.

On the first day, Bette walked in with Calamine lotion smeared all over her face. "What's that for?" asked Wyler. "It's to make me look old," she answered. "You look like a clown. Take it off," Wyler ordered. They argued over her definition of the part. Wyler said he wanted her to put some humanity into her portrayal. "This woman was not supposed to be just evil, but have great charm, humor, and sex." Bette was icy to his wishes, Thomas Brady stated in the New York

Times,

"and each was monstrously patient with the other."

When one scene reached its eighth or ninth take, Wyler accused Bette of rattling off her lines. "Her response was cool enough for a Sonja Henie ice-skating spectacle," said Brady.

Wyler claimed he was trying to get Davis to abandon her usual style of acting. "When speaking of Miss Davis' mannerisms, he minced around the room flailing the air with his arms," said another reporter from the set. Bette, afraid that she was being pushed into the background of the film, insisted on playing with emphatic bitchery.

During the filming of an important dinner scene, Wyler criticized her openly, suggesting that she be replaced by Miriam Hopkins. Bette's reaction to this was to walk off the set. She went to her rented home at Laguna Beach and refused to return to work. After a twenty-one-day absence, when she learned she would forfeit her entire salary

and

be liable for the cost of the production, she returned to the Goldwyn studios.

Actor Herbert Marshall, who played her husband, has described his final scene with the actress. Stricken by a heart seizure, Marshall was to fall on the parlor floor while Bette remained seated nearby, refusing to help him. As the camera remained on Bette's masklike frozen face, her dying husband crawled on the floor behind her, dragging himself toward the steps leading upstairs, where his heart medicine was. The actor, who had only one leg (the other had been lost in World War I), said it was no trouble crawling upstairs: "Because it wasn't me. Once I got out of camera range, Mr. Wyler used a double. I was already in my dressing room, changing, when my double finally got to the top of the stairs."