BELGRADE (4 page)

Authors: David Norris

T

HE

F

ORTRESS ABOVE THE

T

WO

R

IVERS

: T

HE

C

ITY’s

F

OUNDATIONS

ALEMEGDAN

: P

OSITION AND

P

REHISTORY

Belgrade in its Serbian form means White-city (

Beo-grad

), a name vividly evoked by the old fortress as seen from the banks of the two rivers, the Sava and the Danube, which meet below its white walls. The city and its location have often been described in flattering terms by those who have lived here and by visitors from abroad. Miloš Crnjanski, an outstanding figure in twentieth-century Serbian letters, was a poet, novelist and essayist whose work has greatly influenced the literary styles and tastes of modern Belgrade writers. One of his lesser-known books is a travel guide to the city, originally published in French in 1936. He writes about its geographic position in the following terms: “Belgrade sits on a rock rising high over a broad plain. The view encompasses the majestic panorama of the old Serbian provinces of Bačka and Banat, which were also the last to be liberated.”

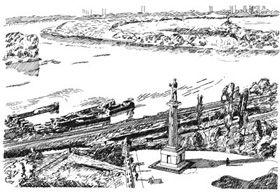

Today we can stand on that rocky outcrop and look out at the view Crnjanski describes from Belgrade’s old Turkish fortress of Kalemegdan, now a public park containing many reminders of the city’s history. It is here that the story of Belgrade begins in all its incarnations: a city ruled by many different regimes and the capital city of various countries—Serbia, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, communist Yugoslavia, and most recently of Serbia again.

Kalemegdan crowns the central district of Belgrade’s old town. A towering statue of a naked man with a sword grasped in his right hand and a hawk perched on his left stands on the furthest point of this promontory. The monument, fashioned by the famous Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović (1883–1962), was placed here in 1928 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Serbia’s victory in the First World War on the side of the Allies. It is appropriately named the Victor (Pobednik) and is often the first port of call for visitors to Belgrade.

The confluence of the rivers Sava and Danube lies immediately below, with the flat expanse of Vojvodina, the lands of Bačka and Banat, stretching northward toward the borders with Croatia, Hungary and Romania. In the distance, overlooking the Danube, the conurbation of Zemun is identifiable by its tall “millennium tower” of 1896 visible on a hilltop. In a different direction, bridges span the Sava to join the old town with the serried rows of tower blocks and wide avenues of New Belgrade, built only after the Second World War. An island occupies the central part of the watery junction giving a staging post from one bank to another. The island was often used by armies laying siege to the town, hence its ominous name of Great War Island (Veliko ratno ostrvo).

All the natural advantages of the city’s position are to be seen from the platform around the Victor’s base. The fortress walls offer clear lines of sight over comparatively large distances, and the rivers on two sides provide both defensive potential and navigation routes in three directions. Yet such a naturally advantageous location has not saved Belgrade from attack and it has frequently been occupied, then lost and fought over again. Each time a new town has sprung up in place of the old one. Slobodan Glumac offers a telling comment testifying to the city’s stormy past in his book

Belgrade

:

The history books say that Belgrade was razed and put to the torch forty times. This, then, would mean that it was rebuilt forty-one times. Yet different each time, different from the preceding community, almost as if to deny its very existence.

These words from 1989 bear an almost prophetic tone, coinciding with the time when Belgrade was on the verge of another major transformation, as the country of which it was then capital was about to dissolve in the Wars of Yugoslav Succession.

The flat land of Vojvodina to the north was in some very far and distant past covered by a vast tract of water, the Pannonian Sea, which is still yielding occasional examples of prehistoric fossils. Archaeologists have also found plenty of evidence of life from more recent prehistory in the vicinity of Kalemegdan, which reveals that it has been a base for human activity for some eight thousand years. There are two large archaeological sites from the Neolithic period fairly close by. The closer one is to be found at Vinča, about ten miles from the centre of Belgrade. The other is situated further down the Danube at Lepenski Vir in the direction of the Black Sea where the startling remains of a settlement going back to 6000 BC were unearthed. The research undertaken on the very rich and varied finds from these diggings has been of huge significance for international scholarship in deepening our understanding of Neolithic communities, their methods of husbandry, their religious rites and culture generally. Objects from this period of the late Stone Age are on display in the National Museum (Narodni muzej) and the City Museum of Belgrade (Muzej grada Beograda).

Although pickings from Kalemegdan and around the city centre itself have been sparser, there is evidence to support the view that a small settlement was established here in about the same period. Perhaps it functioned as a lookout post, a watchtower for the larger groups downriver. Later, tribes of Illyrians, Thracians and Dacians passed through here in periods of migratory activity during the Bronze Age from about 2000 BC to 800 BC.

Evidence of early knowledge about Belgrade’s geographical location comes from the myths and legends passed down from generation to generation. The Homeric world knew that two important rivers met and provided a crossroads at this promontory. The rock overlooking the confluence has been identified as one of the places in the story of Jason and the Argonauts. Returning with the Golden Fleece, Jason and his crew sailed from the Black Sea up the Danube, then turned and steered down the Sava and followed its course in order to find an outlet into the Adriatic Sea before heading south for home. Greek classical authors, including Hesiod, have also left indications that they were aware of this location. From these Greek chroniclers we know that the Celts began to arrive in the area from the fourth century BC during their migration westward. They brought with them the culture and technology of the Iron Age, which they put to good use, soon driving out the Bronze-Age tribes who lived here. One of these Celtish tribes, the Singi, settled on the rock above the Sava and Danube where they built a simple wooden fortification in the third century BC.

There are those, including Miloš Crnjanski, who maintain that some place-names around Belgrade have retained Celtic roots. Looking at the names of rivers, for example, Crnjanski writes that it is a mistake to think that the Sava and the Drava are somehow Slavonic words since they come from the Celtic roots

aw

and

dur

meaning water. (It has to be said that this etymological link has never been conclusively proven.) But whatever the truth of the debate, the site on which Kalemegdan Park now stands has played a significant role in events in the Balkan Peninsula since long before the birth of Christ. Different peoples and cultures from the ancient world have come and gone, each leaving some slight sign of their presence. These traces from archaeological, mythic and textual sources give us some idea of the earliest human activity around this place above the two rivers.

ROM

R

OMAN

C

AMP TO

S

ERBIAN

C

APITAL

The earliest visible traces of previous occupants at Kalemegdan were left by the Roman legions which fought the Celts and took their settlements along the Danube in order to secure the use of the river by Rome. These military missions were sent over a period of some forty years from 35 BC to AD 6. Having chased out the Celts, they began to build forts of their own in order to hold the ground already taken and prepare the way for further conquest in the region. The fort at Belgrade was home to more than 5,000 legionnaires and was one of a series of similar camps along the Danube. In an expansive and confident mood, the Roman conquerors turned to make a more permanent home for themselves, and around AD 69–80 replaced the wooden walls and structures with ones made of stone. They called their new settlement Singidunum, after the Celtish tribe which had prior ownership over the territory, and they stayed for another three centuries. Excavated finds from Belgrade’s Roman period are on display in the National Museum.

As was common practice elsewhere in the empire, Singidunum became more than just a camp with a solely military purpose. On retiring from active service, soldiers would often make a home for themselves in the countryside surrounding their fortress. Meanwhile, Roman power in the region extended in all directions and Singidunum changed from being a frontier outpost to one of the nodal points in the imperial network of roads and river transportation.

The city under Roman management was part of a secure imperial world and enjoyed one of its longest periods of peace and stability. The civilian population of Singidunum continued to grow outside the confines of the sturdy fortress walls, spilling into what is now Belgrade’s central district. Emperors passed through the region on their way to defend the imperial borders from marauding bands of outsiders, like Claudius II who marched his army in 268 via Singidunum to defeat the Goths near what is now the southern Serbian town of Niš.

The Roman Emperor Constantine decided on a step that was to have profound consequences for the development of the Balkans and Europe generally, and which echoes down to the present day. He built a new imperial city on the shores of the Black Sea to be named after himself. Gavro Škrivanić of Belgrade’s Historical Institute, writing in

An Historical Geography of the Balkans

, comments on this development: “Konstantinopolis emerged from the old Greek town of Byzantium and was built under Constantine the Great in AD 330 and proclaimed as the capital of the Roman Empire. It had an exceptionally strategic position, and became one of the largest mercantile and communication centres of the world.” This rival to Rome is better known to the Serbs as Byzantium or Carigrad (City of the Tsar or Emperor); it was later renamed Istanbul after it fell to the Ottoman Empire.

The Roman Empire effectively became two units: a western entity based on the power and the glory of Rome, and an eastern section administered by the new city. The Christian Church took root at the same time, promoted by Constantine who was the first emperor to be baptized, and it too was destined to be divided in two branches. The division was not complete until the Great Schism of 1054 when the leaders of the Church, the Bishop of Rome and the Patriarch in Byzantium, excommunicated one another, thus paving the way for the emergence of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

The political and administrative arrangements for the initial partition of the empire led to a weakening of its defences, and Singidunum’s years of

Pax Romana

came to an end. The city was sacked by Goths in 378 and then again at the hands of Attila the Hun in 441. The local population was condemned to slavery and for nearly a hundred years the city ceased to exist. The Byzantine Emperor Justinian began a programme to rebuild it in 535, changing the name from the Roman Singidunum to the Hellenized version Singidon. The walls were constructed from the remains of the previous Roman fortress along with new stone and brick—handiwork that has left a confusing legacy for later archaeologists to sift through. Justinian’s project was constantly interrupted during the rest of that century by the Avars, another tribe who invaded the Balkans and laid siege to the city three times.

During the sixth and seventh centuries fresh waves of newcomers crossed from the north into the Balkan Peninsula. These latest interlopers were the Slavs who came in search of pasture for their herds and made their way deep into the peninsula. Not much is known of them from this period although they are mentioned by Byzantine chroniclers. They were nomadic peoples who had no form of writing and, consequently, have left behind little evidence about their way of life, customs, rituals or religion. They were converted to Christianity in the ninth century by followers of the monks Cyril and Methodius.

These two brothers were themselves of South Slav origin, from the region of Thessalonica, educated in the Greek rite of the Church, and commissioned by the Byzantine Empire to spread the Gospels among the Slavs. As speakers of a Slavonic dialect, their first task was to develop an alphabet that would make a suitable vehicle for translating the Holy Scriptures into a language comprehensible to all Slavs. The Cyrillic script still bears the name of its inventor who borrowed and adapted Greek letters with numerous additions and modifications in order to accommodate this system of writing to their Slavonic dialect which had some sounds that did not exist in Greek. The Slavs of the ninth century were linguistically much closer than they are today and it was possible to find enough common ground for the brothers’ translations to be widely accepted. Some Slavs, like the Slovenes, Croats and Czechs, later accepted the authority of the Church in Rome and abandoned the Cyrillic alphabet, taking up and using Latin as the

lingua franca

of the written word. Meanwhile, each Slavonic branch of the Orthodox Church, including the Serbs, developed its own liturgical language, influenced by developments in local speech patterns as their dialects evolved into distinct languages with separate although related vocabularies, grammars and pronunciation. The Orthodox Church not only brought the Bible and writing to the Slavs, but it also introduced them to the more sophisticated Byzantine models of social, political, economic and cultural organization which were gradually adopted in secular practices and forms of government.