BELGRADE (31 page)

Authors: David Norris

The last great event, however, was of an altogether different nature, marking the funeral procession of President Tito who died after an illness at the age of 87 in May 1980. His body was brought back to Belgrade for burial by rail from the hospital where he was being treated in Slovenia. His coffin was carried down Knez Miloš Street on a plain gun-carriage, watched by huge crowds mostly in tears lining the pavements, then taken up the hill to Dedinje and his final resting place behind the Museum of 25 May and next to his own villa where he had lived since the end of the war. The occasion was attended by presidents, kings and statesman from around the world in a show of respect for the man who over a remarkable career kept his country united and improved its standing in global politics.

Knez Miloš Street was intended to be a symbol of the new country from the time of its first ruler, housing the highest offices of government and the army. It has served as the showpiece in the capital of the principality of Serbia when it still owed allegiance to the Porte; later in the Kingdom of Serbia; then in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes; the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia; and most recently the Republic of Serbia.

It has also been the scene of other, more violent, events. One of the targets for intensive German bombing in April 1941, it was where one of the war’s catastrophes occurred. A bomb shelter in the grounds of the Church of the Ascension where some 180 people were taking refuge was struck by high explosives. A small memorial in the church grounds today marks where the shelter stood. Nearly sixty years later, some of the government and military buildings on the street were deemed to be legitimate targets by NATO strategists, giving rise to huge damage in 1999. Some buildings have been restored and some are still waiting for sites to be cleared and reconstruction to begin. In 2003 the President of Serbia, Zoran Đinđić, was assassinated in the grounds of the building of the Government of Serbia on the corner with Nemanja as he was leaving to get into his official car at the back of the building. The history of Belgrade seems to demand that its landmarks bear witness equally to all the triumphs and disasters that befall the city.

The end of the street in the nineteenth century was marked with a flourish by a handsome, cobbled square, home to the kafana Mostar. Today it is a junction sitting at the crossroads of a number of important and fast roads. It was built in 1970 to bring the motorway over the River Sava from New Belgrade via the bridge called the Gazelle (Gazela), so-called because its elegant sweep is said to represent an antelope leaping over the water. At this intersection, following from the end of Knez Miloš Street, one road goes down to join Vojvoda Mišić Boulevard, and another crosses straight over into Vojvoda Putnik Boulevard. The lower road leads to the Belgrade Fair (Sajam), which regularly hosts industrial and commercial exhibitions, an annual car show and in October the book fair attended by publishers from home and abroad. Vojvoda Mišić Boulevard then proceeds to the entrance to Ada Ciganlija, the island on the River Sava used by people in Belgrade as a welcome retreat during hot summer weather, and into the Topčider valley via the Belgrade racecourse. Vojvoda Putnik Boulevard goes straight up the hill toward the city’s most prestigious residential district of Dedinje.

These two boulevards are named after famous generals of the Serbian army who held long and distinguished military careers. Radomir Putnik (1847–1917) initially turned back the Austrian invasion of Serbia, then in 1915 was faced with certain defeat by a combined offensive of German, Austrian and Bulgarian armies. He withdrew the whole army across Montenegro and through the mountains of Albania to reach safety on the island of Corfu rather than surrender. Živojin Mišić (1855–1921) served in all the major wars from 1876 to 1918. Leading the Serbian offensive in northern Greece during 1918, he broke through the enemy lines and after just a month and a half brought his men to Belgrade on 1 November.

EDINJE

By the side of the Mostar intersection where Knez Miloš Street joins Vojvoda Putnik Boulevard to go up the hill towards Dedinje stands the brewery originally founded by the Weifert family. After the Second World War it was nationalized and given the more anonymous name of the Belgrade Beer Industry (Beogradska industrija piva), although it has since reverted to its previous name and it is once more possible to buy Weifert beer. Further up the hill, Knez Alexander Karađorđević Boulevard is the lower marker of the elite district of Dedinje. The term is sometimes used to refer to this whole area incorporating Topčider, Košutnjak and Senjak. Strictly speaking, however, it should be confined to the area bounded by the Vojvoda Putnik Boulevard and the ridge at the top of the hill.

The area was formerly known as Dedija or Dedina taken from the Serbian word

deda

, which usually means grandfather but was also applied historically to community elders and particularly heads of religious houses. It is thought that the name has its origin in the fact that, according to an Ottoman census of 1560, a Moslem order of Dervišes from Belgrade owned some land here. At the beginning of the twentieth century the area was known for its orchards, small summer-houses and vineyards kept by some of the rich families in town, who would use their property as a handy retreat from the city.

It owes its transformation into the desirable address that it has represented for nearly a century to King Alexander Karađorđević when he decided to build a new family residence for himself on the ridge of the hill. He chose a spot from where there were long views on all sides, particularly to the south over the wooded Topčider valley. He began to buy up land and between 1924 and 1929 built the Royal Palace (Kraljevski dvor) for himself in the kind of national Byzantine style found in some of the architecture in the centre of Belgrade. The building has a quiet elegance suited to its function as a family home, not an institution of state. Later, as part of the same complex, a new palace was completed in 1936, the White Palace (Beli dvor) in a neoclassical style. Tito used the White Palace as a place for holding state functions and receptions after the Second World War, and since the end of Milošević’s regime the complex has been returned to the Karađorđević family for their use.

King Alexander set a trend with his palace development, which was immediately followed by Belgrade’s wealthier families who built luxury villas for themselves in Dedinje, pushing the city’s boundaries up the hill from Knez Miloš Street. The parkland to the side was planned in the 1930s with pathways for walking and riding and given the name Hyde Park (Hajd park).

Dedinje rapidly became more than just a district of Belgrade. It became a social goal, as a villa in this part of town was taken as a sign of arrival in Belgrade’s high society and represented success, money, sophistication and elegant living. It attracted the attention of foreign representatives who saw the value of having their embassy, or more often an ambassador’s residence, in Dedinje with the more functional embassy building in town.

When the communists arrived in 1944 they took it upon themselves to take over control of Belgrade in all ways, including the symbolic significance of the Dedinje villas. Their goal was not just to assume the outward appearance of having taken power, but to take over the prestige and position of the pre-war elite. To this end they requisitioned the houses in Dedinje, moving out the previous owners and installing themselves and their families. Property was handed out to loyal followers of the Communist Party like a medieval king would give castles and lands to his feudal barons.

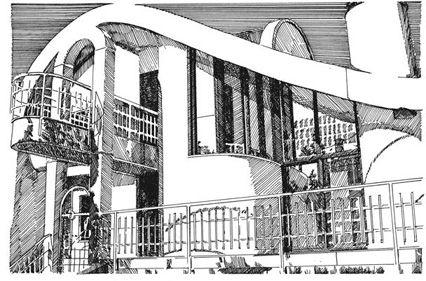

The same mentality dominated among the new elite of the 1990s. They were not interested in emulating the political coup that the communists strove to achieve, but wanted to show the rest of their world that they had truly arrived. Old-style leaders of criminal gangs became new-style businessmen, hiding their origins behind a Dedinje villa. Yet their taste for kitsch styles in dress, music and finally architecture led them to treat their prestige addresses in a different way. They would enlarge the property, or even pull down the original house and replace it with some hugely vulgar monstrosity, ruining the unassuming elegance for which the district was famous. Their trademark has acquired the term “turbo” architecture, coined from the more widely known turbofolk, a fast and furious version of popular music from the 1990s produced by adding disco rhythms to the slower oriental melodies of traditional folk songs.

The basic orientation of “turbo” forms, according to Slobodan Bogunović in his encyclopaedia of Belgrade architecture, is founded on a “reinterpretation and politicization of folklore, a nationalist mania for mythmaking based on incorrect readings of national history”. He characterizes the stylistic content of its architectural design as follows:

The absence of any feeling of measure, an intoxication with physical size, a visible tendency towards a sense of the theatrical overburdened by motifs and details; a somewhat mellow, indulgent and shallow understanding of architectural tradition, alongside a shameless flirting with dreams of a fairytale, ideal home, bring these objects close to the nature of kitsch production and kitsch perception.

These “turbo” blunders mix a layman’s vision of a hi-tech future with a confused sense of the purpose of architecture. They appear to some as a Postmodernist expression in building materials. Yet such a view overlooks the social, economic and political chaos that shaped Belgrade in the 1990s, and the desperate situation of most of its inhabitants as a result of the collapse of Yugoslavia. The appearance of these weird buildings is a sign of those times of crisis, just as the Baroque and classical monumentalism of many of the buildings in the centre is a sign of the city’s early growth and sense of self-confidence.

OUSE OF

F

LOWERS

A little way along Knez Alexander Karađorđević Boulevard, set back from the main road behind a broad swathe of park, stands what used to be the Museum of 25 May. The date is taken from Yugoslavia’s Day of Youth (Dan mladosti), which was also Tito’s birthday. It used to exhibit the official presents that the president received on his state visits to other countries, and items sent to him from various organizations and individuals from within Yugoslavia. It was a shrine to the popularity of Tito, which with the fall of communism became out of place, and the museum no longer exists. The space is used for temporary exhibitions, and the area in front for small musical or theatre performances. Just inside the front door, however, two of Tito’s official cars remain on display. One of them, a Rolls Royce, was slightly damaged during the 1999 bombing campaign. It was kept in a garage at the late president’s villa which became a target when it was rumoured that Milošević was living there.

Another museum used to be close by but is now considered irrelevant in the new times. The Museum of 4 July was dedicated to the Partisan uprising in 1941, as it was in this house, formerly belonging to Vladislav S. Ribnikar, that the leadership of the Yugoslav Communist Party met to organize resistance to the German occupation.

Behind the ex-Museum of 25 May is a small mausoleum, the House of Flowers (Kuća cveća), where Tito’s coffin was laid to rest in 1980. His tomb is made of plain white marble with his name and years of his birth and death in gold letters. The whole building is a modest homage to the man who led the country from the end of the Second World War to 1980. By the side of the House of Flowers is a small museum of artefacts from his life, mainly gifts given on state occasions. Behind the wall lies his former residence, a villa constructed as the family home of Aleksandar Acović in 1934. When Tito arrived in Belgrade at the end of 1944 he lived briefly in the White Palace before moving to 15 Užice Street. The site is now closed to visitors, but the damage caused in 1999 is obvious from the street.

OPČIDER AND

S

URROUNDINGS

Vojvoda Putnik Boulevard continues to climb the hill beside Hyde Park to meet the Topčider Star, or Topčiderska zvezda, a roundabout where seven roads converge. From here the boulevard drops down the other side of the hill with a pleasantly wooded area on the left through which paths cut down to the bottom avoiding the main road. On the other side of the road the slope forms a residential area known as Senjak; its name comes from the Serbian word

seno

, meaning hay. Kalemegdan used to provide storage space for hay until there was a serious fire in 1857 that caused a great deal of damage and presented a serious danger to the fortress and the buildings inside. It was decided, thereafter, for reasons of prudence, that such easily combustible material should not be kept so close to the centre of Belgrade. The collection and storage point for hay was then moved out of town to here, hence Senjak.

This innovation was followed toward the close of the nineteenth century by the building of new industries near the square marking the end of Knez Miloš Street. People looking for work began to migrate to this district and, since it was outside the city boundary and not subject to any planning regulations, built rough dwellings on the slope of Senjak. Not much attention was given to these hastily constructed shacks, thrown up with no regard for any kind of urban plan, until the development of Dedinje as a residential quarter was under way in the 1920s and 1930s. Although it was less prestigious than Dedinje, Senjak was very close and it rose in popularity among Belgrade’s middle classes who replaced the slums with family villas. The old racecourse, the Belgrade Hippodrome, was relocated to the bottom of the Senjak slope from its original site near the Đeram Market on King Alexander Boulevard at the beginning of the twentieth century and, later, the state mint was built close by.