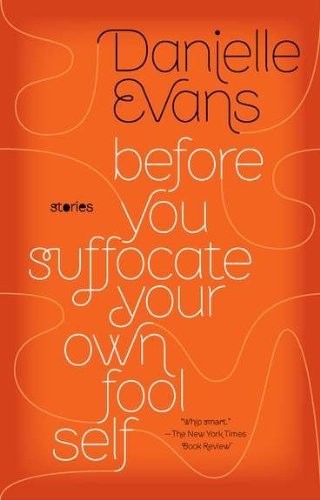

Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self

Read Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self Online

Authors: Danielle Evans

Tags: #Fiction, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Literary

BOOK: Before You Suffocate Your Own Fool Self

9.93Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Table of Contents

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

The following stories have been published previously, in slightly different form: “Virgins” (

The Paris Review

), “Harvest” (

Phoebe

), “Someone Ought to Tell Her There’s Nowhere to Go” (

A Public Space

), “The King of a Vast Empire” (

5 Chapters

), and “Robert E. Lee Is Dead” (

Black Renaissance Noire

).

The Paris Review

), “Harvest” (

Phoebe

), “Someone Ought to Tell Her There’s Nowhere to Go” (

A Public Space

), “The King of a Vast Empire” (

5 Chapters

), and “Robert E. Lee Is Dead” (

Black Renaissance Noire

).

“The Bridge Poem” by Donna Kate Rushin used by permission of the author.

“Between Ourselves.” Copyright © 1976 by Audre Lorde, from

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde

by Audre Lorde. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde

by Audre Lorde. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions. Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Evans, Danielle.

Before you suffocate your own fool self / Danielle Evans. p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-44347-7

1. African American women—Fiction. 2. Self-realization in women—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3605.V3648B

813’.6—dc22

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

I’m sick of mediating with your worst self

On behalf of your better selves

I am sick

Of having to remind you

To breathe

Before you suffocate

Your own fool self

On behalf of your better selves

Of having to remind you

To breathe

Before you suffocate

Your own fool self

—DONNA KATE RUSHIN, “The Bridge Poem”

have made all our lies holy.

—AUDRE LORDE, “Between Ourselves”

Virgins

M

e and Jasmine and Michael were hanging out at Mr. Thompson’s pool. We were fifteen and it was the first weekend after school started, and me and Jasmine were sitting side by side on one of Mr. Thompson’s ripped-up green-and-white lawn chairs, doing each other’s nails while the radio played “Me Against the World.” It was the day after Tupac got shot, and even Hot 97, which hadn’t played any West Coast for months, wasn’t playing anything else. Jasmine kept complaining that Michael smelled like bananas.

e and Jasmine and Michael were hanging out at Mr. Thompson’s pool. We were fifteen and it was the first weekend after school started, and me and Jasmine were sitting side by side on one of Mr. Thompson’s ripped-up green-and-white lawn chairs, doing each other’s nails while the radio played “Me Against the World.” It was the day after Tupac got shot, and even Hot 97, which hadn’t played any West Coast for months, wasn’t playing anything else. Jasmine kept complaining that Michael smelled like bananas.

“Sunscreen,” Jasmine said, “is some white-people shit. That’s them white girls you’ve been hanging out with, got you wearing sunscreen. Black people don’t burn.”

Never mind that Michael was lighter than Jasmine and I was lighter than Michael, and really all three of us burned. Earlier, when Jasmine had gone to the bathroom, I’d let Michael rub sunscreen gently into my back. I guess I smelled like bananas, too, but I couldn’t smell anything but the polish, and I didn’t think she could, either. Jasmine was on about some other stuff.

“You smell like food,” Jasmine said. “I don’t know why you wanna smell like food. Ain’t nobody here gonna lick you because you smell like bananas. Maybe that shit works in Bronxville, but not with us.”

“I don’t want you to lick me,” Michael said. “I don’t know where your mouth has been. I know you don’t never shut it.”

“Shut up,” I said. They were my only two real friends and if they fought I’d’ve had to fix it. I turned up the dial on Mr. Thompson’s radio, which was big and old. The metal had deep scratches on it, and rust spots left by people like us, who didn’t watch to see whether or not we’d flicked drops of water on it. It had a good sound, though. When the song was over they cut to some politician from the city saying again that it was a shame talented young black people kept dying like this, and it was time to do something about it. They’d been saying that all day. Mr. Thompson got up and cut off the radio.

“You live like a thug, you die like a thug,” he said, looking at us. “It’s nothing to cry over when people wake up in the beds they made.”

He was looking for an argument, but I didn’t say nothing, and Jasmine didn’t, either. Part of swimming in Mr. Thompson’s pool was that he was always saying stuff like that. It still beat swimming at the city pool, which had closed for the season last weekend, and before that had been closed for a week after someone got beat up there. When it was open it was crowded and dirty from little kids who peed in it, and was usually full of people who were always trying to start something. People like Michael, who had nothing better to do.

“I’m not crying for nobody,” Michael told Mr. Thompson. “Tupac been dead to me since he dissed B.I.G.” He looked up and made some bootleg version of the sign of the cross, like he was talking about God or something. He must’ve seen it in a movie.

Mr. Thompson shook his head at us and walked back to the lawn chair where he’d been reading the paper. He let it crinkle loudly when he opened it again, like even the sound of someone else reading would make us less ignorant.

Jasmine snorted. She lifted Michael’s sweatshirt with the tips of her thumb and index finger so she didn’t scratch her still-drying polish and pulled out the pictures he had been showing us before Mr. Thompson came over—photos of his latest girlfriend, a brunette with big eyes and enormous breasts, lying on a bed with a lot of ruffles on it.

“You live like a white girl, you act like a white girl,” said Jasmine, frowning at the picture and making her voice deep like she was Mr. Thompson.

“She’s not white,” said Michael. “She’s Italian.”

Jasmine squinted at the girl’s penny-sized pink nipples. “She look white to me.”

“She’s Italian,” said Michael.

“Italian people ain’t white?”

“No.”

“What the fuck are they, then?”

“Italian.”

“Mr. Thompson,” Jasmine called across the yard, “are Italian people white?”

“Ask the Ethiopians,” said Mr. Thompson, and none of us knew what the hell he was talking about, so we all shut up for a minute.

The air started to feel cooler through our swimsuits, and Michael got up, putting his jeans on over his wet swim trunks and pulling his sweatshirt over his head. I followed Jasmine into the house, where we took turns changing in the downstairs bathroom. It was an old house, like most of the ones in his part of town, but Mr. Thompson kept it nice: the wallpaper was peeling a little, but the bathroom was clean. The soap in the soap dish was shaped like a seashell, and it seemed like we were the only ones who ever used it. On our way out we said good-bye to Mr. Thompson, who nodded at us and grunted, “Girls”; then, harsher, at Michael: “Boy.”

Michael rolled his eyes. Michael wasn’t bad. Mostly I thought he hung out with us because he was bored a lot. He needed somebody to chill with when the white girls he was fucking’s parents were home. We didn’t get him in trouble as much as his boys did. We hung out with him because we figured it was easier to have a boy around than not to. Strangers usually thought one of us was with him, and they didn’t know which, so they didn’t bother either of us. When you were alone, men were always wanting something from you. We even wondered about Mr. Thompson sometimes, or at least we never went swimming at his house without Michael with us.

Mr. Thompson was retired, but he used to be our elementary school principal, which is how he was the only person in Mount Vernon we knew with a swimming pool in his backyard. We—and everybody else we knew—lived on the south side, where it was mostly apartment buildings, and if you had a house, you were lucky if your backyard was big enough for a plastic kiddie pool. The bus didn’t go by Mr. Thompson’s house, and it was a twenty-minute walk from our houses even if we walked fast, but it was nicer than swimming at the city pool. We were the only ones he’d told could use his pool anytime.

“It ’s ’cause I collected more than anyone else for the fourth-grade can drive, when we got the computers,” I said. “He likes me.”

“Nah,” Jasmine said, “he don’t even remember that. It’s ’cause my mom worked at the school all those years.”

Jasmine’s mom had been one of the lunch ladies, and we’d gone out of our way to pretend not to know her, with her hairnet cutting a line into her broad forehead, her face all covered in sweat. Even when she got home she’d smell like grease for hours. Sometimes if my mother made me a bag lunch, I’d split it with Jasmine so we didn’t have to go through the lunch line and hear the other kids laugh. At school, Mr. Thompson had been nicer to Jasmine’s mother than we had. We felt bad for letting Mr. Thompson make us nervous. He was the smartest man either of us knew, and probably he was just being nice. We were not stupid, though. We’d had enough nice guys suddenly look at us the wrong way.

My first kiss was with a boy who’d said he’d walk me home and a block later was licking my mouth. The first time a guy had ever touched me—like touched me

there

—I was eleven and he was sixteen and a lifeguard at the city pool. We’d been playing chicken and when he put me down he held me against the cement and put his fingers in me, and I wasn’t scared or anything, just cold and surprised. When I told Jasmine later she said he did that to everyone, her too. Michael kept people like that out of our way. People had used to say that he was fucking one of us, or trying to, but it wasn’t like that. He was our friend, and he’d moved on to white girls from Bronxville anyway. It was like he didn’t even see us like girls sometimes, and that felt nice because mostly everybody else did.

there

—I was eleven and he was sixteen and a lifeguard at the city pool. We’d been playing chicken and when he put me down he held me against the cement and put his fingers in me, and I wasn’t scared or anything, just cold and surprised. When I told Jasmine later she said he did that to everyone, her too. Michael kept people like that out of our way. People had used to say that he was fucking one of us, or trying to, but it wasn’t like that. He was our friend, and he’d moved on to white girls from Bronxville anyway. It was like he didn’t even see us like girls sometimes, and that felt nice because mostly everybody else did.

Michael’s brother Ron

was leaned up against his car, waiting for him at the bottom of Mr. Thompson’s hill. The car was a brown Cadillac that was older than Ron, who graduated from our high school last spring and worked at Radio Shack. People didn’t usually notice the car much because they were too busy looking at Ron and he knew it. He was golden-colored, with curly hair and doll-baby eyelashes and the kind of smile where you could count all of his teeth. Jasmine always said how fine he was, but to me he looked like the kind of person who should be on television, not someone you’d actually wanna talk to. He must’ve still been mad at Pac, too, or he was just tired of hearing him on the radio, because he was bumping Nas from the tape deck. Michael hopped in the front seat and started to wave bye to us.

was leaned up against his car, waiting for him at the bottom of Mr. Thompson’s hill. The car was a brown Cadillac that was older than Ron, who graduated from our high school last spring and worked at Radio Shack. People didn’t usually notice the car much because they were too busy looking at Ron and he knew it. He was golden-colored, with curly hair and doll-baby eyelashes and the kind of smile where you could count all of his teeth. Jasmine always said how fine he was, but to me he looked like the kind of person who should be on television, not someone you’d actually wanna talk to. He must’ve still been mad at Pac, too, or he was just tired of hearing him on the radio, because he was bumping Nas from the tape deck. Michael hopped in the front seat and started to wave bye to us.

Other books

The Smoky Mountain Mist by PAULA GRAVES

The Portable Edgar Allan Poe by Edgar Allan Poe

What Matters Most: The Billionaire Bargains, Book 2 by Erin Nicholas

Una virgen de más by Lindsey Davis

Blind Justice by William Bernhardt

My Merlin Awakening by Ardis, Priya

El Valor de los Recuerdos by Carlos A. Paramio Danta

Zombie Attack! Rise of the Horde by Devan Sagliani

Irresistible Nemesis by Annalynne Russo

A Man Like Mike by Lee, Sami