Baudolino (43 page)

Authors: Umberto Eco

Tags: #Historical, #Fantasy, #Adventure, #Contemporary, #Religion

"But farther ahead," he assured them, "we'll find only Christians, though they may be Nestorians."

"Good," Baudolino said, "if they're Nestorians, they're at least of the Priest's race, but from now on, before we say anything, we must take care, when we enter a village, to see if there are crosses and spires."

Spires, indeed! What they found were clumps of mud huts, and even if they included a church, you couldn't recognize it. These were people who were content with very little in order to praise the Lord.

"But are you sure Zosimos went this way?" Baudolino asked. And Ardzrouni told him to rest assured. One evening Baudolino saw him as he was observing the setting sun, and he seemed to be taking measurements in the sky with his arms outstretched and the fingers of his two hands entwined, as if to form some little triangular windows through which he peered at the clouds. Baudolino asked him why, and he said he was trying to discern the location of the big mountain beneath which the sun vanished every evening, under the great arch of the tabernacle.

"Madonna santissima!" Baudolino shouted. "Don't tell me you also believe in the story of the tabernacle like Zosimos and Cosmas Indicopleustes?"

"Of course, I do," Ardzrouni said, as if they were asking him if water was wet. "Otherwise how could I be so sure that we're following the same road Zosimos must have taken?"

"Then you know the map of Cosmas that Zosimos kept promising us?"

"I don't know what Zosimos promised you, but I have the map of Cosmas." He drew a parchment from his sack and showed it to the friends.

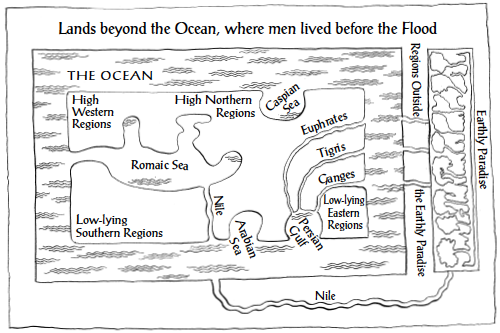

"There! You see? This is the frame of the Ocean. Beyond, there are lands where Noah lived before the Flood. Towards the eastern extreme of those lands, separated by the Ocean from regions inhabited by monstrous beingsâand these are the lands through which we will have to passâthere is the Earthly Paradise. It's easy to see how, setting out from this blessed land, the Tigris, the Euphrates, and the Ganges pass beneath the Ocean to cross the regions towards which we are traveling, and then they empty into the Persian Gulf, whereas the Nile follows a more tortuous path through the antediluvian lands, enters the Ocean, resumes its course in the lower southern regions, and more precisely in the land of Egypt, emptying first into the Romaic Gulf, which the Latins call the Mediterranean, and thence into the Hellespont. Here, we must follow the route to the east, to encounter first the Euphrates, then the Tigris, then the Ganges, and turn towards the lower eastern regions."

"But," the Poet interjected, "if the kingdom of Prester John is very close to the Earthly Paradise, must we cross the Ocean to reach it?"

"It's close to the Earthly Paradise, but this side of the Ocean," Ardzrouni said. "But we will have to cross the Sambatyon...."

"The Sambatyon, the river of stone," Solomon said, clasping his hands. "So Eldad did not lie, and this is the road towards finding the lost tribes!"

"We mentioned the Sambatyon also in the Priest's letter," Baudolino said sharply, "and so obviously it must exist somewhere. Very well, the Lord has come to our aid, he has caused us to lose Zosimos, but he has allowed us to find Ardzrouni, who apparently knows more."

One day they saw, at a distance, a sumptuous temple, with columns and a decorated tympanum. But, nearing it, they saw that the temple was only a façade; the rest was a cliff, and, in fact, that entrance was up high, set into the mountain, and it was necessary to climb, God knows how, up to where the birds fly, in order to reach it. On more careful study, they saw that, along the circle of surrounding mountains, other façades stood out on high against steep walls of lava, and at times they had to narrow their eyes to distinguish the carved stone from the stone shaped by Nature, and they could also make out sculpted capitals, fornices and arches, and superb colonnades. The inhabitants, down below, spoke a language very similar to Greek, and said that their city was named Bacanor, but what they saw were churches of a thousand years past, when the place was under the dominion of Aleksandros, a great king of the Greeks, who honored a prophet who had died on a cross. By now they had forgotten how to climb to the temple, nor did they know what was still inside it, and they preferred to honor the gods (they actually said gods and not the Lord God) in the open, in an enclosed space, in the center of which stood the gilded head of a buffalo on a wooden stake.

That very day the entire city was celebrating the funeral of a young man whom all had loved. On the flat area at the foot of the mountain a banquet had been laid out, and in the center of the circle of tables already laden there was an altar with the body of the deceased on it. Up above, in broad curves, lower and lower, flew eagles, kites, ravens, and other birds of prey, as if they had been bidden to this feast. All dressed in white, the father approached the corpse, cut off its head with an axe, and placed it on a golden plate. Then some smiths, also dressed in white, cut the body into little pieces, and the guests were invited each to take one of those pieces and throw it to a bird, which caught it in midair, then vanished into the distance. Someone explained to Baudolino that the birds carried the dead man into Paradise, and for them their rite was far superior to those of other peoples, who allowed the body of the dead to rot in the earth. Then all sat down at the tables and each tasted the flesh of the head until, with only the skull remaining, clean and shiny as if it were metal, they made it into a cup from which all drank in joy, praising the departed.

Another time, they were crossing, for a week, an ocean of sand, which rose like the great waves of the sea, and it seemed that everything moved beneath their feet and beneath the horses' hoofs. Solomon, who had already suffered seasickness after embarking at Gallipolis, spent those days in continuous bouts of vomiting, but he could vomit very little because the party had been able to swallow very little, and it was lucky they had provided themselves with an ample supply of water before facing this predicament. Abdul began then to suffer fever and chills, which continued to torment him for the rest of the journey, preventing him from singing his songs, as the friends invited him to do when they stopped in the moonlight.

Sometimes they proceeded rapidly, over grassy meadows, and, not having to combat hostile elements, Boron and Ardzrouni conducted endless debates on the question that obsessed them, namely, the vacuum.

Boron employed his familiar arguments: that if there were a vacuum in the universe, nothing would prevent the existence, beyond our worlds, in the vacuum, of other worlds, et cetera, et cetera. But Ardzrouni pointed out that he was confusing the universal vacuum, which could be debated, with the vacuum created in the interstices between one corpuscle and another. And when Boron asked him what these corpuscles were, his opponent reminded him that, according to certain ancient Greek philosophers, and other wise Arab theologians, the followers of Kalam, namely, the Motokallimun, one should not think that bodies are solid substances. The whole universe, everything that is in it, and we ourselves are composed of indivisible corpuscles, which are called atoms, whose incessant movement is the origin of life. The movement of these corpuscles is the very condition of all generation and corruption. And between one atom and another, precisely in order for them to be able to move freely, is the vacuum. Without the vacuum between the corpuscles that compose every body, nothing could be cut, broken, or shattered, nor could it absorb water, or be invaded by heat or cold. How does nourishment spread in our body, if not by traveling through the empty spaces between the corpuscles that compose us? Stick a needle, Ardzrouni said, into a swollen bladder, before it begins to deflate only because the needle, moving, widens the hole it has made. How is it that for an instant the needle remains in the bladder that is still full of air? Because it is insinuated into the interstitial vacuum between the corpuscles of air.

"Your corpuscles are a heresy, and nobody has ever seen them except your Arabs, those Kallemotemum, or whatever you call them," Boron replied. "While the needle is entering, a bit of air is already escaping, leaving space for the needle."

"Then take an empty flask, immerge it in water with the neck down. The water won't enter, because there's air. Suck the air from the flask, close it with one finger so more air won't enter, immerge it in the water, remove your finger, and water will enter where you have created the vacuum."

"Water rises because Nature acts in such a way that the vacuum is not created. The vacuum is against Nature, and being against Nature it cannot exist in Nature."

"But while the water rises, and it doesn't rise abruptly, what is there in the part of the flask that is not yet filled, since you have removed the air?"

"When you suck out the air you eliminate only the cold air, which moves slowly, but you leave an amount of hot air, which moves rapidly. The water enters and immediately causes the hot air to escape."

"Now you again pick up that flask full of air, but heated, so that inside there is only hot air. Then you immerge it, neck down. Although it contains only hot air, water still won't enter. So the heat of the air is irrelevant."

"Oh, is it? Take the flask again, and on the bottom, towards the belly of the flask, make a little hole. Immerge it in the water, hole first. The water won't enter because there is air inside. Then put your lips to the neck, which has remained out of the water, and suck out all the air. Gradually, as you suck out the air, the water rises through the lower hole. Then pull the flask out of the water, keeping the upper hole closed, so the air won't press to enter. So you see that the water remains in the flask and doesn't escape by the lower hole, thanks to the disgust that Nature would feel if it left a vacuum."

"The water doesn't descend the second time because it rose the first, and a body cannot make a movement opposed to the first if it doesn't receive a new stimulus. Now listen to this. Stick a needle into a swollen bladder, allow all the air to escape, wffff, immediately close the hole made by the needle. Then, put your fingers on both sides of the bladder, as you might pull the skin here on your hand. And you see that the bladder opens. What is there in that bladder whose walls you have widened? The vacuum."

"Who told you the walls of the bladder will part?"

"Try it!"

"No, not I. I'm not a mechanic, I'm a philosopher, and I reach my conclusions on the basis of thought. Anyway, if the bladder opens, it's because it has pores, and after it is deflated, a bit of air has entered through the pores."

"Oh, really? First of all, what are pores if not empty spaces? And how can the air enter on its own if you have not imposed a movement on it? And whyâonce you have taken the air from the bladderâdoesn't it swell up again spontaneously? If there are pores, then, when the bladder is swollen and well closed and you press it, imposing a movement on the air, why doesn't the bladder deflate? Because the pores are, true enough, empty spaces, but smaller than the corpuscles of air. Keep pressing harder and harder, and you'll see. Then leave the swollen bladder for a few hours in the sun, and you'll see that, little by little, it deflates on its own, because the heat transforms the cold air into hot air, which escapes more rapidly."

"Then take a flask..."

"With a hole on the bottom or without?"

"Without. Immerge it completely, tilted, into the water. You will see that, as the water gradually enters, the air emerges and goes plop plop, thus manifesting its presence. Now pull out the flask, empty it, suck out all the air, close its mouth with your thumb, put it tilted into the water, remove your thumb. The water enters but without your hearing or seeing any plop plop. Because inside there was the vacuum."

At this point the Poet yet again interrupted them to remind them that Ardzrouni should not be distracted, because with all that plop plop and those flasks everybody was growing thirsty, their bladders were now empty, and it would be wise to head for a river or some other place more damp than where they were.

Every now and then they heard something of Zosimos. This man had seen him, another had heard of a man with a black beard who was asking about the kingdom of Prester John. At which our friends would ask eagerly: "And what did you tell him?" The answer was almost always that they had told him what everyone in those lands knew, that Prester John was to the east, but it took years to arrive there.

Foaming with anger, the Poet said that in the manuscripts of the Saint Victoire library you could read that those who had traveled in those places did nothing but come upon splendid cities, with temples whose roofs were covered with emeralds, and palaces with golden ceilings, columns with ebony capitals, statues that seemed alive, golden altars with seventy steps, walls of pure sapphire, stones so luminous that they cast more light than torches, mountains of crystal, rivers of diamonds, gardens with trees emanating scented balms that permit the inhabitants to live by simply breathing in their odor, monasteries where only highly colored peacocks are bred, whose flesh does not undergo corruption, and, taken on a journey, that flesh lasts for thirty days or more even under a blazing sun, never causing a bad smell, and then glittering fountains whose water shines like the light of a thunderbolt and, if you put in it a salted fish, the fish would return to life and dart off, a sign that this is the fountain of eternal youth. But they so far had seen desert, scrub, massifs where you couldn't even rest on the stones because they would cook your buttocks, the only cities they had encountered were made of wretched hovels inhabited by repugnant rabble, like Colondiophontas, where they had seen the Artabants, men who walk prone like sheep, or like Iambut, where they had hoped to rest after having crossed seared plains, and the women, if not beautiful, weren't too ugly, but they discovered that, faithful to their husbands, they kept poisonous snakes in their vagina to defend their chastityâand if they had at least mentioned it beforehand, but no: one woman pretended to give herself to the Poet, who came close to having to accept perpetual chastity, and he was lucky because he heard the hiss and sprang back. Near the Catardese swamps they encountered men with testicles down to their knees, and at Necuveran, people naked as wild animals, who mated in the street like dogs, the father coupled with the daughter and the son with the mother. At Tana they met anthropophagi, who fortunately would not eat foreigners, whom they found revolting, but only their own children. By the river Arlon they came upon a village where the inhabitants danced around an idol and with sharpened knives inflicted wounds on themselves, in every limb, then the idol was placed on a wagon and borne through the streets, and many of the people joyfully flung themselves under the wagon's wheels, breaking their bones to the point of death. At Salibut they crossed a wood infested with fleas as big as frogs, at Cariamaria they met hairy men who barked, and not even Baudolino could understand their language, and women with boar's teeth, hair to their feet, and a cow's tail.