Battleship Bismarck (40 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

So sure was Lütjens that the

Bismarck

would not survive the approaching battle that early on the morning of 27 May he decided to have the Fleet War Diary taken to safety in France. He realized that it would be of inestimable value not only for the Seekriegsleitung but for any analyst of Exercise Rhine to know:

Why he, an experienced and successful leader of Atlantic operations, did not take the B-Dienst’s radio signal of 21 May, which told him that the British had been alerted, as a warning that they would intensify their surveillance of the Denmark Strait as well as to the south of it, and adjust his plans accordingly. Did Group North’s signals of 22 May, telling him that his departure from Norway had apparently not been noticed and that the British were searching too far to the south, remove any concern he may have had about being detected as he went north? Did he unquestioningly accept what these messages said?

Why he did not postpone Exercise Rhine and turn away when he first encountered the

Suffolk

and

Norfolk

, as he did during the corresponding phase of his operation with the

Scharnhorst

and

Gneisenau

three months earlier.

Why, when he held his course, he did not make an all-out attempt to sink his shadowers.

Why he abandoned the pursuit of the obviously hard-hit

Prince of Wales

, thereby renouncing the possibility of achieving another apparently easy and important victory.

Why he interrupted Exercise Rhine so soon after the battle off Iceland and tried to reach port.

Why, on the evening of 24 May, he suddenly viewed the

Bismarck’s

fuel situation as so critical that he had to steer for St. Nazaire by the shortest route instead of making a detour into the Atlantic, which might have been our salvation.

Why, on the morning of 25 May, he thought the enemy still knew our position.

The diary would also show exactly when on the night of 24–25 May and at what intervals the

Bismarck

made the gradual change of course to starboard that led to the breaking of contact.

Between 0500 and 0600 one of our planes was put on the catapult and made ready to carry the War Diary to safety. With full power, we maneuvered to turn the starboard end of the catapult into the wind so that the plane could fly off. Nothing happened. The compressed-air line to the catapult was bent. Another effort to launch was made, but again nothing happened. The track was unusable. We had no means of making the necessary repair and, after some discussion, the launching was canceled. Obviously, the Arado could not be left on the catapult, where in battle it would be a fire hazard. So, with its wings folded and holes made in its floats, it was pushed to the end of the track and tipped overboard. I watched it drift by and disappear.

*

I don’t know what damaged the catapult, but I suspect it was the hit that shattered one of our service boats during the battle off Iceland.

In another effort to get the War Diary to safety in the short time remaining before the final action, at 0710 Lütjens radioed Group West, “Send a U-boat to save War Diary.” That was his last radio signal home.

Send a U-boat! That was the last hope, the vague possibility of saving the War Diary. With the failure to launch the Arado, the

Bismarck

had exhausted her own means of carrying out that mission. And, with the dispatch of the message to Group West, there was nothing Lütjens could do towards the fulfillment of his wish but wait for the outside world to respond. Wait and wait.

At first, of course, Lütjens had reason to suppose that a U-boat would be sent. In fact, at 0801, Group West informed him,

“U-556

will pick up War Diary.” But as the morning wore on, no U-boat appeared. Presumably, so I thought then, there was none near enough or none that had enough fuel to detour to us.

In order to understand why we never saw the

U-556

it is necessary to go back a day.

On 26 May, when dispositions were being made to support the

Bismarck

in her increasingly critical situation, new instructions were sent to the U-boats in the Bay of Biscay. One of those boats was the

U-556

, whose commanding officer, Kapitänleutnant Herbert Wohlfarth, was ordered to reconnoiter and operate in the area of the

Bismarck’s

most recently reported position. When Wohlfarth received those orders, he was on his way home from a patrol that began on 1 May. Therefore, he was low on fuel and, on his way to the

Bismarck

, he would have to be extremely economical with what he had left. Furthermore, he had expended all his torpedoes against British convoys.

Wohlfarth reached the immediate area around the

Bismarck

on the evening of 26 May. Around 1950 he saw the

Renown

and the

Ark Royal

coming out of the mist at high speed—the big ships of Force H. Nothing for it but to submerge. “Enemy bows on, 10 degrees to starboard, without destroyers, without zigzagging,” as Wohlfarth later described it. He would not even have had to run to launch torpedoes. All he would have had to do was position himself between the

Renown

and the

Ark Royal

and fire, at both almost simultaneously. If only he had some torpedoes! He had seen activity on the carrier’s flight deck. Perhaps he could have helped us. Yes, perhaps—that is what he thought at the time. But what he saw was the activity after the launching of the second and decisive attack on the

Bismarck. So

, even if he had torpedoes, he would not have been able to save us from the rudder hit. The Swordfish had long since banked over the

Sheffield

and were just about to attack us.

Fifty minutes later, at 2039, Wohlfarth surfaced and made a radio

report: “Enemy in view, a battleship, an aircraft carrier, course 115°, enemy is proceeding at high speed. Position 48° 20’ north, 16° 20’ west.” Wohlfarth intended his report to be picked up by any of his comrades who might be in the vicinity and able to maneuver to attack. Then he proceeded on the surface at full speed behind the

Renown

and the

Ark Royal.

Their course to the

Bismarck

coincided almost exactly with his own. Every now and again, he submerged and took sound bearings to both ships, but after 2200 he could no longer hear them. The race between his little boat and the two big ships was an unequal contest.

At 2330 Wohlfarth, then 420 nautical miles west of Brest, gave the alarm again. A destroyer came out of the mist at high speed. Once more, he quickly dove. He had reached a depth of thirty meters when the enemy passed him, her propellers making a devilish row. Relieved, he noted in his War Diary: “Fingers crossed again, no depth charges!”

It was probably one of Vian’s destroyers, but at that moment she was not interested in a U-boat. She was too busy trying to shadow and torpedo the

Bismarck.

Another entry in Wohlfarth’s War Diary reads: “27.5.0000, [wind] northwest 5, seaway 5, rain squalls, moderate visibility, very dark night. Surfaced. What can I do for the

Bismarck!

I can see star shells being fired and flashes from the

Bismarck’s

guns. It is a terrible feeling to be near and not to be able to do anything. All I can do is reconnoiter and lead in boats that have torpedoes. I am keeping contact at the limit of visibility, reporting the position, and sending directional signals to call up the other boats.”

At 0352: “I am moving around on the east side to the south, in order to be in the direction of the activity. I soon reach the limit of what I can do in view of my fuel supply. Otherwise I won’t get home.”

0400: “The seas are rising ever higher.

Bismarck

still fighting. Reported weather for the Luftwaffe.”

Around 0630 Wohlfarth sighted the

U-74

, one of the other boats that had been in the Bay of Biscay. Optically and by megaphone, he transferred the mission of maintaining contact with the

Bismarck

to her commanding officer, Kapitänleutnant Eitel-Friedrich Kentrat. He gave Kentrat the

Bismarck’s

position, which he based on his observations of the star shells fired during the night, adding: “I have not seen her directly. You assume contact. I have no more fuel.” And after blinking a greeting to Kentrat, he turned away.

In his War Diary Wohlfarth wrote: “Around 0630 gave last contact report, sighted

U-74

, by visual means gave

U-74

the mission of maintaining contact. I can stay on the scene only by using my electric motors at slow speeds. Above water I need fuel and would have to retire.”

After transferring his mission, Wohlfarth promptly submerged and did not surface again until 1200, a time at which radio signals were routinely repeated. That was when he heard for the first time the order radioed to him between 0700 and 0800 to pick up the

Bismarck’s

War Diary. Having no more idea than had the headquarters ashore that in the meantime the

Bismarck

had sunk, he immediately asked Commander in Chief, U-Boats, to transfer this mission to Kentrat.

*

In the course of the morning Wohlfarth did hear a series of explosions, but had no way of interpreting their significance.

By the time Kentrat received the radio order issued in response to Wohlfarth’s signal, “U-boat Ken trat pick up

Bismarck

War Diary,” he could only search in vain.

I still see it as something more than a coincidence that the

U-556

was the boat ordered to pick up the

Bismarck’s

War Diary because, to us on board, the

U-556

was no ordinary U-boat. There was a very special bond between the little boat and the giant battleship. Both were built at Blohm & Voss and in the summer of 1940 they were often neighbors on the ways. When the

U-556

was commissioned, the mighty bow of the

Bismarck

towered over her. Wohlfarth, who was known in naval circles as “Sir Parsifal,” decided that the commissioning ceremony would not be complete without a band and, since a U-boat certainly did not carry one, he would ask the big neighbor, which as Fleet Flagship had a band—called the Fleet Band—to provide the music. Accordingly, he went to see Lindemann, but he did not go empty-handed. In exchange, he offered the

Bismarck

the Patenschaft

*

of his boat. Lindemann readily accepted. Wohlfarth got

his band and thereafter his artistically designed Patenschaftsurkunde

*

hung in the

Bismarck.

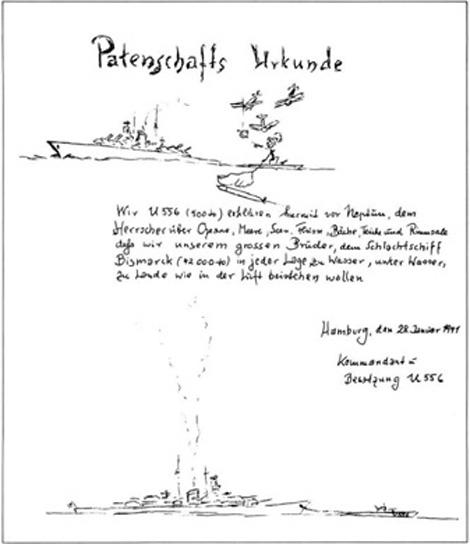

The Patenschaftsurkunde of the

U-556

for the

Bismarck.

(Courtesy of Herbert Wohlfarth.)

Lindemann and Wohlfarth became friends. At the beginning of 1941 the

Bismarck

and the

U-556

were together during gunnery exercises in the Baltic, and once even used the same target. The

U-556

, which Lindemann had allowed to precede him, damaged the target so badly with ten hits that the

Bismarck

could not use it that day. Lindemann, however, did not take it amiss and soon dispelled Wohlfarth’s fear that he would be greeted with an ill-humored reaction, “I do not begrudge you that in the least. I wish that you may have as much and rapid success in the Atlantic and win the Knight’s Cross for it.” Relieved, Wohlfarth replied, “I hope we both receive the Knight’s Cross in the common struggle in the Atlantic.”

†

Wohlfarth heard over the radio about the sinking of the

Hood

during the operation he had just ended against convoys. At first he could not believe it. Now, only two days later, the situation of the

Bismarck

was drastically different, almost hopeless. What did his Patenschaftsurkunde say? “We, the

U-556

(500 tons), hereby declare before Neptune, the ruler of the oceans, lakes, seas, rivers, brooks, ponds, and rills, that we will stand beside our big brother, the battleship

Bismarck

(42,000 tons), whatever may befall her on water, land, or in the air. Hamburg, 28 January 1941. The captain and crew of the

U-556.

” One of the two sketches on the certificate shows “Sir Parsifal” warding off aircraft attacking the

Bismarck

with a sword in his right hand and stopping torpedoes coming towards her with his left thumb. The other sketch shows the

Bismarck

being towed by the

U-556.

It almost seemed as though Wohlfarth had the gift of prophecy when he prepared that certificate.

Help against aircraft and torpedoes, and then a tow. That was exactly what the

Bismarck

needed, and he, of all people, Godfather Wohlfarth, was near her. But he was powerless to help her.

*

The

Bismarck’s

reconstructed War Diary states that, while we were trying to launch the Arado, waves were washing over the upper deck of the ship and some of the men of the 10.5-centimeter flak crews were washed overboard. Also, we were listing so far to port that our 15-centimeter turrets on that side were under water. I cannot reconcile this entry with reality. There being no action in progress or, as it appeared, in immediate prospect between 0500 and 0600, I went to watch the aircraft being launched. It is true that the ship was listing to port, but our 15-centimeter turrets were certainly not under water at the time. Furthermore, our beamy ship was doing so little rolling that it would not have been possible for any members of the flak crews to be washed overboard from the still-elevated superstructure deck. I did not observe conditions such as those described in the diary until about twenty minutes before the ship sank.