Battleship Bismarck (17 page)

Read Battleship Bismarck Online

Authors: Burkard Baron Von Mullenheim-Rechberg

Then fifty-one years old, Lütjens was an undemonstrative man, tall and thin, with dark, serious eyes. He entered the Imperial Navy as a cadet in 1907 and first saw the world from the heavy cruiser

Freya

the same year. After completing the required courses at the Naval School and graduating twentieth out of a total of 160 midshipmen in his class, in 1909 he had his first sea duty in a position of responsibility in a big ship. That tour was followed by many years in the sort of training assignments with which he was to be repeatedly entrusted, officer training and development of the torpedo-boat flotillas. Thus, from 1911 to 1912 he was the officer in charge of naval cadets in the heavy cruiser

Hansa.

During the First World War he served in torpedo boats, winding up as a commanding officer and half-flotilla leader of the Flanders Torpedo Boat Flotilla. In the years following the war, he commanded torpedo-boat flotillas, served on the Naval Staff in Berlin, and was captain of the

Karlsruhe.

In the year 1937, as a rear admiral, he became Chief, Torpedo Boats. Soon after the Second World War broke out, Lütjens, then a vice admiral, was in command of reconnaissance forces in the North Sea. As a deputy of the Fleet Commander, he led the covering forces, the

Scharnhorst

and

Gneisenau

, during the invasion of Norway. In July 1940 he assumed command of the fleet and was promoted admiral in September of the same year. In February and March 1941, he gained operational experience striking at British supply lines in the previously mentioned Atlantic sortie of his flagship

Gneisenau

and the

Scharnhorst.

This experience proved useful to him in a new operation aboard the mighty

Bismarck.

Günther Lütjens, right, shown here as captain of the cruiser

Karlsruhe.

This photo, taken as his ship neared the equator on 24 November 1934, records Admiral Triton’s visit on board in preparation for the appearance of King Neptune the next day. From left to right: Admiral Triton’s aide-de-camp; Admiral Triton; a chief petty officer; the

Karlsruhe’s

First Officer, Korvettenkapitän Schiller; and Lütjens. (Photograph from the author’s collection.)

From left to right: Dr. Hans-Günther Busch, Dr. Hans-Joachim Krüger, and Dr. Rolf Hinrichsen, the ship’s dental officer, on the bridge of the

Bismarck.

(Photograph courtesy of Frau Erika Busch.)

Throughout his career Lütjens was seen by both his superiors and his peers as a highly intelligent, able, and courageous man of action. Although his serious, dry disposition and reserve made it difficult for his more outgoing comrades to get close to him, this forbidding exterior concealed a noble and chivalrous character. When he spoke, which he did in a quick and lively manner, it was evident that his thought processes were equally lively.

On the morning of 13 May, the fleet staff conducted the tests on board, as had been announced, and inspected and tried out the ship’s internal communications facilities. A morning was ample time for that. When at noon the staff disembarked to return to Gotenhafen in the tender

Hela

, the newcomers among our crew were an experience richer. They had seen how, just as in times past a commander led his troops into battle, so now, in the Nelson tradition, the Fleet Commander would exercise command in action. He would be as close to death as anyone else on board. He would have no more of a rear echelon in which to take refuge than would a corpsman.

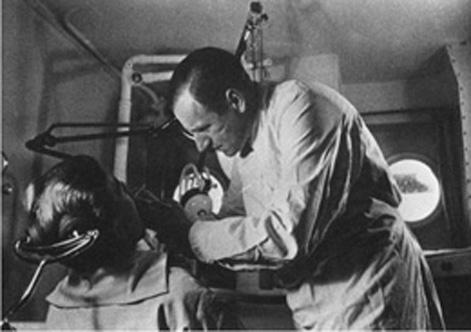

Dr. Rolf Hinrichsen treating a dental patient on board. (Photograph courtesy of Frau Erika Busch.)

In many ways, it must have seemed to the greenhorns in the crew that their ship belonged less to the world of war than to the world of modern industry. Many of them worked in confined spaces, far from the light of day, their eyes on pressure gauges and indicators, their hands on valves and levers, as they struggled to keep a wandering pointer at the proper place on a dial. Bound to their stations, they would have to manipulate their precision instruments with cool deliberation, even in the heat of battle. Their world was not that of the infantryman, who can release tension during an attack by such satisfying means as firing his rifle; it was a stationary world of highly specialized technology. The hardest test of their physical and psychological endurance, of course, would come in actual combat.

By order of the Fleet Commander, that same afternoon the

Bismarck

again exercised at refueling over the bow with the

Prinz Eugen.

Lütjens was particularly concerned that the ships be letter-perfect at this maneuver, because of the circumstances to be anticipated in the operational zone. In the event the enemy should appear when the

Bismarck

had fuel lines over her bow, she was to be released immediately from the tanker so that she could make her way unhindered.

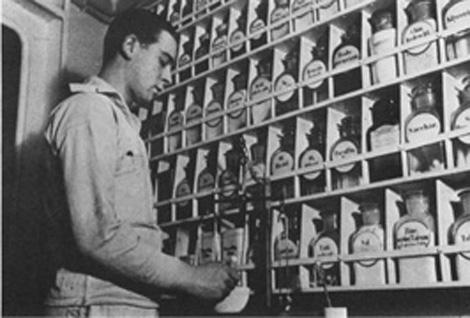

In the

Bismarck’s

dispensary, bars kept the bottles of medicines and drugs from falling off the shelves in heavy seas or when the big guns fired. (Photograph courtesy of Frau Erika Busch.)

On 14 May, we carried out reconnaissance and combat evolutions with the light cruiser

Leipzig

, which was then training in the Gulf of Danzig. The reconnaissance was conducted by our aircraft, whose crews took the opportunity to get in some more practice by “attacking” one another. In the midst of these exercises one of the cranes used for hoisting in aircraft suddenly broke down and all practice came to a premature end. Since repair of the crane was urgent and could not be done with the means available in the ship, we went in to Gotenhafen, where it was to be offloaded. This was by no means our first experience with a malfunctioning crane. Indeed, in the War Diary Lindemann described our cranes as “extremely susceptible to

damage and unreliable.” He reported this new incident to higher headquarters, adding that he could not yet predict when his ship would be back to a state of operational readiness. In the wardroom First Officer Oels and the electrical engineer, Korvettenkapitän (Ingenieurwesen) Wilhelm Freytag, resumed their grumbling about the sorry state of our cranes, but this time the trouble was remedied surprisingly fast. We had gone to all the trouble of offloading oil so that the ship could pass through the shallows at the entrance to Gotenhafen Harbor, but it proved unnecessary to remove the crane. A mechanic from the crane’s manufacturer came aboard and repaired the damage in about an hour. Meantime, however, Group North had reacted to Lindemann’s message by postponing our departure for Exercise Rhine for at least three days.

In those beautiful May days of 1941 we were only too glad to be able to spend our free hours ashore. We found Gotenhafen rather dreary, however. Originally named Gdynia by the Poles and later called Gdingen by the Prussians, it was a small fishing village until after the First World War, when it was incorporated into Poland and developed into a naval base and commercial port. It had 130,000 inhabitants when in 1939, following the conquest of Poland, the Germans named it Gotenhafen and began to convert it into a major naval base. Being beyond the range of enemy bombers at the outset of the war, it made an ideal base for ships in battle training.

We preferred to go to Danzig or to Zoppot, which was still closer but, because of wartime conditions, rather deserted. The beach and pier at Zoppot invited visits. Both these places were easy to reach by rail, and my good friend Kapitänleutnant (Ingenieurwesen) Emil Jahreis, nicknamed “Seppel,” and I spent many happy hours together in one or the other. Bar-hopping in Danzig one evening, we were asked by an acquaintance, “When won’t we see you again? Of course, we know you can’t say. One day you just won’t come, and then maybe we’ll read about you in Wehrmacht reports.”

Another time, after a tour of the bars in Zoppot, we returned to our hotel very late. When we woke up, the sun told us that the

Bismarck

must have long since sailed for her at-sea exercises. Springing out of bed, we made for Gotenhafen with lightning speed. Would we have the undeserved good luck to find a neighborly tug in the harbor? We did. As we neared the

Bismarck

, which had stopped for us, we saw, standing on the upper deck, where we would have to go alongside, a man we had no great desire to see at that moment: Hans Oels who, as First Officer, was primarily responsible for the discipline of the ship. If at all possible, everyone, whether officer, petty officer or enlisted man, made a circuit around Hans Oels, the unapproachable, whom the crew called the loneliest man on board. This time, with his usual aloofness, he let matters rest by saying: “The captain awaits you on the bridge.”

Kapitänleutnant Emil Jahreis, right, shown here as an ensign (engineering) performing an experiment in chemistry class at the Naval College at Kiel-Wik in 1931 or 1932. (Photograph from the author’s collection.)

“Well,” said Lindemann, with a kindly smile, when we rather sheepishly appeared on the bridge, “go on about your duties!”

Seppel Jahreis from Ottingen, Bavaria—he loved life and was always cheerful. In those last weeks in Gotenhafen, however, a change came over him. He became unusually quiet and seemed depressed. I had the feeling that a foreboding of what was to come weighed on him. Most of all, however, he suffered, even if he didn’t say so, from his sudden and to him incomprehensible transfer from the post of turbine engineer to that of chief of damage control. Since the beginning of the building course he had become so familiar with “his” turbines and so humanly close to the turbine crew that the mandatory change tormented him. It was a fateful change. His successor in the engine room survived the sinking of the ship.