Baseball's Hall of Fame or Hall of Shame (3 page)

Cap Anson was the first player to accumulate 3,000 hits, totaling 3,418 safeties in over 10,000 at-bats during his long and illustrious career, spent mostly with the Chicago Cubs. He led the league in runs batted in a record nine times, topping 100 RBIs seven times, and also won two batting titles, hitting over .350 seven different times and finishing his career with a .333 average. He also scored more than 100 runs six times. Anson had perhaps his finest all-around season for the Cubs in 1886. That year, he hit 10 home runs, knocked in 147 runs, batted .371, and scored 117 runs.

Unfortunately, Anson’s character did not match his playing ability, since he was known to have had a major influence on the barring of black players from major league baseball. Prior to a game during the 1885 season in which the opposing team intended to field a black player, Anson threatened to organize a players’ strike to bar black players from competing in the major leagues. His threat achieved its desired result and succeeded in clandestinely barring blacks from the majors, albeit unofficially, until 1947. His induction into the Hall of Fame is a prime example of the manner in which the institution’s rules regarding the judging of candidates based on “integrity and sportsmanship,” among other things, have often been ignored. It also symbolizes one of the great hypocrisies that the Hall of Fame, as well as baseball in general, has come to represent.

Willie McCovey/Harmon Killebrew

Neither Willie McCovey nor Harmon Killebrew could be included among the very greatest first basemen of all time. They were both slow afoot, below average defensively, and were somewhat one-dimensional on offense, failing to hit for a particularly high batting average over the course of their respective careers. However, both men were big run producers who possessed awesome power. During their careers, both McCovey and Killebrew surpassed the 500 home run mark, and also drove in well over 1,500 runs. Those figures were enough to justify their selections to the Hall of Fame.

Willie McCovey hit 521 homers and drove in 1,555 runs during his 22-year career. He led the National League in home runs three times, and in runs batted in twice, leading the league in both categories in two straight seasons (1968 and 1969). McCovey was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player in 1969 when he hit 45 homers, knocked in 126 runs, and batted .320. He also finished in the top ten in the voting three other times. McCovey was a six-time All-Star, and was probably the most feared hitter in baseball for much of the pitching-dominated 1960s. During his career, McCovey topped the 30-homer mark seven times, surpassing 40 on two separate occasions. He also knocked in more than 100 runs four times, scored more than 100 runs twice, and batted over .300 twice. Although he faced stiff competition from Harmon Killebrew and Orlando Cepeda, McCovey was arguably the best first baseman in baseball for much of the period extending from 1963 to 1970. He was certainly the sport’s top first baseman in 1963 (44 HR, 102 RBIs, 103 RUNS, .280 AVG), 1966 (36 HR, 96 RBIs, .295 AVG), and from 1968 to 1970, when he averaged 40 home runs and 119 runs batted in per season.

Harmon Killebrew, in almost the same number of at-bats as McCovey, hit even more home runs (573) and drove in even more runs (1,584). Those numbers more than make up for the fact that his lifetime batting average was only .256. He has the fourth highest home run-to-at-bat ratio in the history of the game (behind only Mark McGwire, Babe Ruth and Ralph Kiner), and he hit more home runs than any other righthanded batter in American League history. Killebrew led the league in home runs six times, runs batted in three times, walks four times, and slugging once. He topped the 40-homer mark eight times, knocked in more than 100 runs nine times, and drew over 100 walks seven times. Like McCovey, he won his league’s MVP Award in 1969. That year, he led the A.L. with 49 home runs, 140 runs batted in, and 145 walks, while batting .276. Killebrew was an 11-time All-Star and, although he split time at other positions during his career, was the top first baseman in the American League for most of the 1960s. It could also be argued that he was one of the five or six best players in the league from 1959 to 1970.

Johnny Mize/Jim Bottomley

Although neither man should be viewed as a clear-cut choice, both Johnny Mize and Jim Bottomley are deserving of their places in Cooperstown because they were very, very good players who were each the best first baseman in the National League for extended periods of time.

Johnny Mize hit 359 home runs, drove in 1,337 runs, and batted .312 during an abbreviated career in which he lost three years due to time spent in the military. He led the N.L. in home runs four times, hitting 51 for the Giants in 1947. He also led the league in runs batted in three times, batting average once, and slugging percentage four times. Playing from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s, during a fairly good era for hitters, Mize knocked in more than 100 runs eight times, scored over 100 runs five times, and batted over .300 nine times, topping the .340 mark twice. He was a 10-time All-Star, and he fared well in the MVP voting as well, finishing second twice, third once, and in the top 10 on three other occasions. Mize was the best first baseman in the National League from 1937 to 1948, with the exception of the three years he was in the military, and also 1941, when Dolph Camilli of the Dodgers won the league’s Most Valuable Player Award. He was arguably the best first baseman in the game in 1940 (43 HR, 137 RBIs, 111 RUNS, .314 AVG), 1942 (26 HR, 110 RBIs, .305 AVG), 1946 (22 HR, 70 RBIs, .337 AVG, in only 101 games), and 1947 (51 HR, 138 RBIs, 137 RUNS, .302 AVG).

In his book,

Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?,

Bill James describes Jim Bottomley as a “good ballplayer” and as a “marginal Hall of Famer at best.” While James’ book is informative insightful, and makes some very interesting points, he also makes mistakes and, in my opinion, errors in judgment. This is a prime example. While not a great player, Bottomley was a very good one and a worthy Hall of Famer. (James lost a great deal of credibility when he predicted in his book, published in 1994, that future Hall of Famers included the likes of Ruben Sierra, Lou Whitaker, Brett Butler, Joe Carter, Al Oliver, and Alan Trammell—all good players, but none, with the possible exceptions of Oliver and Trammell, even close to being Hall of Fame caliber). Anyway, back to Bottomley.

During an era in which a lot of runs were scored, Jim Bottomley was one of the game’s best run-producers. Playing for the St. Louis Cardinals, in the six seasons from 1924 to 1929 he drove in 756 runs, averaging 126 RBIs per year over that stretch. Bottomley led the National League in that department twice, and also topped the circuit in home runs once. During his career, Bottomley batted over .300 nine times, topping the .340-mark three times, and hitting as high as .371 in 1923. He also had more than 10 triples in a season nine times, reaching the 20-mark once, in 1928. In fact, in that 1928 season Bottomley was named the league’s Most Valuable Player for hitting 31 home runs, knocking in 136 runs, scoring 123 others, batting .325, and collecting 42 doubles. His feat that season of hitting more than 20 homers, 20 triples and 20 doubles makes him one of only six players in baseball history to reach the 20-mark in each category in the same season. Bottomley was clearly the National League’s best first baseman from 1925 to 1928, and he also rivaled the Giants’ George Kelly and Bill Terry in 1924 and 1929, respectively. He was the best first baseman in baseball in 1925, when he finished with 21 homers, 128 runs batted in, a batting average of .367, 227 hits, 12 triples, and 44 doubles.

Jake Beckley

Jake Beckley is an interesting case because his career actually spanned three different eras. During his first five seasons (1888-1892), the pitcher’s mound was only 50 feet from home plate. Needless to say, pitchers dominated the sport during that period, with most hitters posting below normal batting averages. However, after the mound was moved back to 60 feet, 6 inches prior to the 1893 season, batting averages began to soar. In 1892, the league average was a paltry .245, but it rose to an all-time high of .309 by 1894. Thus, from 1893 to 1900, Beckley was the beneficiary of the rules changes that went into effect at the beginning of that period. However, the rules of the game were altered once more at the turn of the century, once again shifting the balance of power back to the pitchers. Included in these rules changes were an increase in the size of the strike zone and the further deadening of the ball. As a result, Beckley’s last seven seasons were spent hitting in a pitcher’s era once again. It seems, therefore, that his numbers can basically be taken at face value. Doing so causes one to think that the Veterans Committee did not make a bad choice when it voted him into the Hall of Fame in 1971.

Beckley played more games at first base than any player in history, except for Eddie Murray. Along the way, he compiled a lifetime .308 batting average, totaling 2,931 hits in 9,527 at-bats, scoring 1,600 runs, and driving in 1,575 others. He also accumulated 243 triples and stole 315 bases. Beckley drove in more than 100 runs four times, scored more than 100 runs five times, batted over .300 fourteen times, surpassing the .330-mark on six separate occasions, and finished with at least 10 triples thirteen times. He had his most productive season for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1894, when he knocked in 120 runs, scored 121 others, and batted .343. Beckley was arguably the best first baseman in the game from 1893 to 1895, and then again, from 1899 to 1903. While he may not have been a great player, Beckley was a very good one and, at the very least, a marginal Hall of Famer.

Mule Suttles/Ben Taylor

Although they were polar opposites as players, Suttles and Taylor have been grouped together here because they are generally considered to be, with the exception of Buck Leonard, the two greatest first basemen in Negro League history. As such, it would seem that they were both worthy of their 2006 Hall of Fame inductions.

George “Mule” Suttles played for nine different teams during a 22-year Negro League career that began with the Birmingham Black Barons in 1923. Suttles was a tremendous righthanded power hitter who, using a 50-ounce bat, generated as much power as anyone in black baseball. He was a free-swinging lowball hitter who was known for hitting towering, tape measure home runs. It is said that he once hit a ball completely out of Havana’s Tropical Park that was later measured at close to 600 feet. Suttles’ prodigious power enabled him to lead the Negro National League in home runs twice. Suttles, though, was more than just a slugger. Although he struck out frequently, the six-foot three-inch, 215-pound first baseman maintained a consistently high batting average throughout his career, finishing with a mark of either .321, .329, or .338, depending on the source. He is also credited with a lifetime batting average of .374, with five home runs, in 26 exhibition games against white major leaguers. Suttles was elected five times to represent his team in the East-West All-Star Game, and played for three championship teams during his Negro League career.

On the flip side, Suttles’ limited mobility made him a below-average fielder. Yet, it is said that the hulking first baseman handled almost everything he could reach, and his hitting prowess more than compensated for his defensive deficiencies. The late Chico Renfroe, former Kansas City Monarchs infielder and longtime sports editor of the

Atlanta Daily World

, referred to Suttles as the hitter who “had the most raw power of any player I’ve ever seen. He went after the ball viciously! He wasn’t a finesse player at all. He just overpowered the opposition.”

While Mule Suttles was a pure slugger, Ben Taylor was a scientific hitter, known for his ability to hit line drives to all fields, and for his proficiency at executing the hit-and-run play. Generally considered to be the premier Negro League first baseman of the first quarter of the twentieth century, Taylor spent 20 years in black baseball, splitting time between 11 different teams. An extremely productive offensive player, Taylor posted a .334 lifetime batting average. He is credited with having batted over .300 in fifteen of his first sixteen seasons in baseball.

In addition to being an outstanding lefthanded batter, Taylor was a smooth defensive first baseman who made difficult plays look easy. An excellent teacher as well, it was Taylor who helped Buck Leonard refine his skills as a first baseman.

Orlando Cepeda/Tony Perez

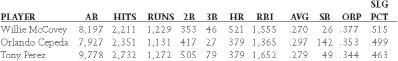

Now we are getting into a very gray area. Neither Orlando Cepeda nor Tony Perez was a great player, but both were very good. At their peaks, Cepeda was probably a little better, but Perez was a good player for a longer period of time. As a result, his career numbers compare favorably to those of Cepeda in most categories. Let’s take a look at the statistics compiled by both men, alongside those of Willie McCovey, a contemporary of both players who we have already identified as a legitimate Hall of Famer: