Banjo of Destiny (3 page)

Authors: Cary Fagan

What a Broken Chair Is Good For

JEREMIAH PRINTED

off photos and plans from the internet. That was the first step. The next was to gather up the necessary materials.

Since his parents had forbidden him to buy a banjo, he didn't think he should buy any of the materials, either. So he had to find everything he needed. After all, wasn't that what a lot of banjo players did a hundred years ago?

Finding a metal cookie tin turned out to be easy. There was one in the pantry with only three cookies left in it. It was a pretty tin, decorated on the sides with old winter scenes of people skating on a pond and sledding on white hills.

After Jeremiah ate the cookies, he said to the cook, “I guess you don't need this old tin.”

“What would I need it for? Keeping all my love letters? Now you skedaddle out of my kitchen.” She waved a spatula at him, as if this time she might really tap him on the nose. Jeremiah tucked the cookie tin under his arm and ran up to his room.

He had his banjo pot!

Finding the wood for the instrument's neck wasn't quite so easy. It had to be at least twenty inches long. Since Jeremiah didn't know how to use any tools, the piece of wood had to be pretty close to the right size already. Straight and flat for the fingerboard. Narrow but not too narrow.

Jeremiah hunted around the four-car garage, but all he found was a pile of logs to feed the three fireplaces. Maybe a Tennessee woodsman could hack one into a banjo neck with his ax, but Jeremiah certainly couldn't.

He went down to the basement and found some lengths of cedar left over from the walls of the sauna. But cedar was too soft. He'd read on the internet that he needed a hardwood, or the neck would bend from the force of the string tension.

Jeremiah took walks along the road, hoping to find just the right piece of wood. He looked in trash cans and behind garages. But all he found was a cracked ping-pong paddle, a portable hair dryer with a missing cord, and a torn lamp shade.

Whatever a person might make out of those things, it wasn't a banjo.

One day after school he was crossing the grounds of the house. Feeling discouraged, his hands deep in the pockets of his uniform jacket, he came across the family gardener.

Wilson was tall, skinny and tanned from working outside. He carried a folded-up wooden lawn chair under his arm.

“Hey, Jeremiah, what's shaking?”

“Not much. What's with the chair?”

“Busted. The seat's ripped and one of the folding hinges rusted and broke. It served its masters well but now it has to go to the chair cemetery. That is, the garbage dump.”

“Can I see it?”

Jeremiah took the chair from Wilson and looked it over. The legs on it were flat on the sides, looking kind of like giant Popsicle sticks. The back legs were longer.

Maybe long enough. Maybe wide enough, too.

“You look pretty deep in thought,” said Wilson.

“Do you think that's a hardwood?” he asked.

“Must be, otherwise the chair wouldn't have been able to hold up your uncle Mel, if you know what I mean. Maybe maple.”

“Then I think I have a way to recycle this chair. I think it still has some life in it.”

“As the saying goes,” Wilson said, “one man's junk is another man's gold.”

â¢â¢â¢

THE GOAL OF

Fernwood Academy was to encourage not only academic excellence but “well-rounded young men and women with practical skills for real life.” Students took culinary arts in one semester and industrial design the next â what regular schools called cooking and shop.

Jeremiah had rather liked cooking. Mixing ingredients reminded him of making potions as a little kid, when the cook had allowed him to pour just about anything into a bowl, mush it about and put it in the oven. (He remembered insisting that Monroe sample his Tuna-Pea Soup-Chile Pepper-Chocolate Surprise.) In class he had made lopsided zucchini muffins and runny goat-cheese omelets.

Shop was a different matter. The blowtorches and electric sanders scared him. His last project, a wire key rack, had ended up looking like the skeleton of some small extinct animal.

Luella, on the hand, was good at shop. Her parents actually

used

her key rack.

“This year,” said Ms. Threap, the shop teacher, “we're going to continue the rack theme. Only this time we're all going to make wine racks. Won't that be fun and useful? Won't your moms and dads be thrilled to have a place to store their chardonnays and pinot noirs?”

“My parents drink beer,” whispered Luella.

“Less talk and more work,” said Ms. Threap.

Jeremiah knew this was his chance. He was a little afraid of Ms. Threap, who barked like a drill sergeant and wore earrings that looked like miniature power saws. He looked back at Luella, who gave him an encouraging nod.

“Ms. Threap?”

“Yes, Larry?”

“Jeremiah.”

“That's what I said. What can I do you for?”

“I was wondering if I could make something else for my project.”

“Something else?” Ms. Threap put her hands on her hips. “A wine rack not good enough for you, eh? You want to build maybe a houseboat? Or a jet engine?”

“I want to build a banjo.”

“I'm sorry, Larry, but you'd better stick to the wine rack. Unless you'd like to try to make another key rack. Perhaps one that doesn't look like a rat trap.”

“I really want to make a banjo,” he said. “I've got the material. I've even got some plans and pictures.”

“Plans? Now that's a horse of a different color. Let me see them.”

Jeremiah hurried to pull the plans from his briefcase. Ms. Threap spread them out on a work table.

“Well, this doesn't look too hard,” she said. “Not with a little assistance from yours truly.”

“I'd appreciate all the help I can get,” Jeremiah said.

Ms. Threap straightened up and smiled. “You're on, Larry. You can build a banjo. Personally, I prefer the sound of the accordion. I just love my Friday night polka group. But that's another kettle of fish. Let's get you started.”

The first step was to take some measurements. Jeremiah had managed to sneak the broken chair to school. With Ms. Threap's help, he saw that the leg was indeed long enough, and just wide enough, too. She showed him how to use a pencil and triangle to make a line and then use a saw to cut the leg from the rest of chair.

When it was free, he unclamped it from the vice and held it in his hands. It felt more like a fence post than a banjo neck, but it was a start.

The next task was harder. A banjo neck was narrower at the top. Ms. Threap showed him how to use a chisel and a wooden mallet to carefully chip away at the wood.

Jeremiah worked for the whole class and then came back at the end of the day. When the hand holding the chisel slipped, his heart jumped. For a moment he thought that he had cracked the whole neck instead of just chipping off a bit.

Finally Mrs. Threap said she had to close up, and he brushed the wood chips from his clothes and ran to find Monroe waiting with the limousine.

He climbed into the passenger seat.

“I've been waiting almost an hour,” Monroe said.

“I'm sorry. I had some extra work to do.”

“It isn't me I'm worried about. You've missed your ballroom dancing lesson.”

Jeremiah groaned. “Mom and Dad aren't going to be too happy.”

“Not only that,” said Monroe. “Today you were going to learn how to rumba.”

Pedagogical Study Number Eight

JEREMIAH'S PARENTS

were indeed displeased to hear that he had missed ballroom dancing. But Jeremiah told them that he had been working on a particularly ambitious industrial design project that would require extra hours. He asked whether he could, just temporarily, of course, skip some of his after-school activities.

“Industrial design is a much more important subject than most people realize,” Jeremiah said. “I mean, just think of the design work that went into the dental-floss dispenser.”

“That's true,” said his father. “What do you think, Abigail?”

His mother finished arranging some rare orchids in a vase. “I don't think missing a few classes would hurt. Except piano, of course.”

“Thanks!” Jeremiah hugged them both.

“So what is this ambitious project you're building?” his father asked.

Jeremiah froze. Slowly he looked to the left and right and then over his parents' heads so he didn't have to look them in the eyes.

“I'd like to keep it a surprise. Would that be okay?”

“I know,” his mother said. “It's for my birthday, isn't it? Oh, don't tell me. Do you think I'm going to be very surprised?”

Jeremiah nodded. “Pretty surprised.”

â¢â¢â¢

PERHAPS JEREMIAH

would have enjoyed the piano more if he had had a different teacher. But Jeremiah's parents insisted that he study with Maestro Boris, a retired concert pianist famous for screaming, ripping up sheet music and tossing it like confetti, strangling himself, thrashing his cane in the air, and otherwise striking terror in the hearts of his students.

When the Maestro swept in, Jeremiah was already seated at the Hoosendorfer Deluxe Concert Grand. His frightened reflection gazed back at him from its brilliant black surface.

Maestro Boris clapped his hands.

“Begin!” he commanded. “Pedagogical Study Number Eight. You have been practicing, yes? Let me hear.”

The piece was from the Maestro's own book of music compositions. Jeremiah tried to steady his shaking hands.

He was not even halfway through when the Maestro began rapping his cane on the floor like a series of gunshots.

“No, no, no! A thousand times no! Do you think that is how Horowitz would have played it? Or Rubinstein? You sound as if you are wearing hockey gloves. You must be light, carefree, a butterfly flitting from branch to branch. And look how you slouch! Sit up, be proud. Now try again!”

Jeremiah started at the beginning, the Maestro banged his cane, and on it went.

When the half hour was over, the Maestro took his silk handkerchief from his pocket and wiped the sweat from his brow. Jeremiah's mother came into the room with an envelope of crisp bills, which was how the Maestro preferred to be paid.

“I am wasting my time,” the Maestro said, peeking into the envelope and then tucking it inside his jacket. “Your son is without a shred of talent. He has no ear. I think maybe he even has no soul.”

“Please, Maestro Boris, don't give up. The student talent night is almost here. We think it's just so very important for Jeremiah's self-esteem that he perform. He will try harder. Won't you, Jeremiah?”

Jeremiah thought

no.

Jeremiah said, “Yes.”

“As you wish,” the Maestro said with a sigh. “Perhaps next time you might have a glass of red wine waiting for me. Something French and very dry.”

“Yes, of course,” said Jeremiah's mother. “We're just so grateful for your efforts.”

“Of course you are,” said the Maestro, sweeping out of the house.

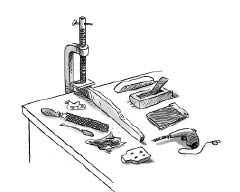

After the Maestro was gone, Jeremiah went down to the basement. His father had put a workshop next to the ultramodern furnace and air-conditioning system, so that Wilson could fix things. A long wooden workbench stood along the wall, with vices attached to it. On a pegboard hung hammers, chisels, saws, rasps.

Jeremiah had brought the length of wood home from school. Ms. Threap said the next stage was to round the back of the banjo neck so that his hand could wrap comfortably around it and slide up and down to play the fingerboard. Ms. Threap had told him how to put the wood in a vice and use a rasp, holding it in two hands and pushing it across to shave the wood.

Shaping the neck was tiring. The wood shavings tickled Jeremiah's nose and made him sneeze. But very slowly the back of the neck began to look rounded. When his arms ached too much to go on, he swept up the shavings and went upstairs. Then he took a long soak in the marble hot tub that was so big he could have shared it with a couple of hippos.

Afterwards, Jeremiah lay on his bed with his headphones on. He listened to Glen Smith playing “Sourwood Mountain” and Tommy Jarrell playing and singing “John Brown's Dream.” Glen Smith had a quick, rough, plucky sound while Tommy Jarrell was precise and chiming.

They weren't trying to sound like anybody else, thought Jeremiah. They just sounded like themselves.

â¢â¢â¢

JEREMIAH COULDN'T

work on his banjo for the next three days because his parents made him take his after-school lessons. And after dinner he had to practice piano for the talent night.

He did work on the banjo in shop class, though. Ms. Threap showed him how to smooth the rounded back of the neck with sandpaper.

“Getting there,” Ms. Threap said. “But not smooth enough. You want it smooth as silk. You need to use at least two more grades of extra-fine sandpaper.”

That evening, just as Jeremiah and his parents were finishing dinner, the doorbell rang. The maid let in Luella.

“How nice to see you, dear,” said Jeremiah's mother. “You're just in time for dessert.”

“I've already eaten, actually. Is that a sour cream caramel soufflé? Well, in that case...” She sat across from Jeremiah. “Really I just came by to see how Jeremiah is doing on hisâ¦umâ¦project.” She forked up some soufflé. “Yum,” she murmured.

“Jeremiah's been very dedicated to his industrial design project,” his father said. “It's really very gratifying to see that he's inherited some of his mother's and my determination.”

“Yes, very gratifying,” said Luella, only it sounded like

wery grawifieen

due to a large mouthful of soufflé.

“And of course we can't wait to see it,” said Jeremiah's mother.

Luella swallowed. “Oh, you'll be thrilled at what your little J.B. has got up to.”

“Let's go downstairs,” Jeremiah said firmly. “Now.”

“Just let me finish this. It's fantastic. What is that wonderful flavor I detect, Mrs. B.? Ginger? No. Vanilla?”

Jeremiah's mother smiled. “Something French. It's called Cointreau.”

“Well, it's sure yummy. Maybe I'll just have a little smidgen more⦔

Luella took her time finishing. She slowly wiped her mouth on a napkin. Then she thanked his parents again.

At last they were excused and went down the hall to the back stairway to the basement.

“For a minute there,” Jeremiah said, “I thought you were going to climb onto the table and lick the bowl.”

They went into the workroom and Jeremiah turned on the light.

“I wish I'd thought of that.”

The neck lay on the table.

“Wow,” Luella said, running her hand over the wood. “It really looks like the neck of an instrument. It's nice and smooth, too. Is it done?”

“I've just got to use the last fine sandpaper.”

“Man, I'd never have the patience.”

“I want it to be a real instrument, as good as I can make it. And you know what? It's fun. At least some of the time.”

Jeremiah picked up a fresh piece of sandpaper and went to work. The sandpaper made a soft

ssshhh

as it went over the wood.

While he put his energy into his arms, Luella talked. She was practicing a violin piece for the recital. She actually liked playing the violin. And she liked her violin teacher, Ms. Purcell, who always gave her a chocolate and told her she was doing very well although perhaps just a little more practicing would be helpful.

“Hey, I was thinking,” she said. “How are you going to learn to play the banjo, anyway? I don't suppose your parents are going to let you take banjo lessons considering the fact they don't even know you're building one.”

Jeremiah grinned. “I thought of that.” He reached under the workbench and pulled out a DVD case. There was a picture on it of a man with a neatly trimmed red beard, a banjo in his hands.

“âElements of Clawhammer Banjo

,'”

Luella read aloud. “Well, I hope Red Beard is a good teacher.”

“I've already watched it about a million times,” Jeremiah said. “But practicing with a tennis racket isn't exactly satisfying.”

“And watching you use sandpaper is about as interesting as, well, watching you use sandpaper. I'm going home to watch reruns of

Friends

. See you, Hayseed.”

“Hayseed?”

“I think it suits you.”

“Well, it doesn't. Never call me that at school.”

“Don't worry, I'm not that mean. You don't have to see me out. I know the way, Hayseed.”

â¢â¢â¢

WITH MS. THREAP

watching over his shoulder, Jeremiah cut the headstock from a cross-piece of the folding chair. He drilled a hole for each of the tuners that would go in. Then he used a plane to shave down the top of the neck to a slanted angle and glue the headstock to it. To make sure the strings wouldn't pull the headstock right off, he put in a couple of screws.

“Not as elegant as a woodworker's joint, Larry,” Ms. Threap said. “But it works.”

Jeremiah would have worked on the banjo even more if he hadn't had to practice for talent night.

He was the seventeenth performer of the evening. Before him came six violin players (including Luella), two cellists, five pianists (three of whom also performed “Pedagogical Study Number Eight”), a trombone player, a jazz dancer, and a boy who recited the “To be or not to be” speech from

Hamlet.

Jeremiah found himself daydreaming during the speech â

To be a banjo player or not to be, that is the question.

Whether 'tis nobler to suffer the slings and arrows of disapproving parents

Or

â

And then suddenly his name was being called, and he found himself moving like a robot up the aisle and onto the stage.

He sat on the bench and looked at the keys that seemed to stretch away from him forever. He felt hot, unable to breathe. But he began to play.

As if they didn't belong to him, his hands moved too quickly, messed up and then stopped. He started again, this time too slowly so that he had to speed up. And then all of a sudden he started playing from the beginning again.

Jeremiah lurched from note to note, too soft in some parts and then almost slamming down his hands.

Kids in the audience giggled. Maestro Boris, who had come to hear his students perform, muttered darkly from the back.

His ears burning, Jeremiah hurried down the aisle, tripping on his shoelace.

“Hey, Birnbaum,” hissed a voice from the aisle. It was an older boy named Damien Mills. Damien was a big, doughy boy who considered himself the funniest kid in school, even if nobody else did. “You got mixed up, Birnbaum. You must have thought it was lack-of-talent night.”

Jeremiah practically dived back into his seat.

“Don't worry,” his mother whispered, patting his hand. “We'll help you get over those nerves. I know just what to do. We'll hire a sports psychologist.”

“A what?” said Jeremiah miserably.

“He works with famous athletes. To help them overcome their performance anxiety before a big game. And when the next talent night comes around at the end of the year â just wait and see!”