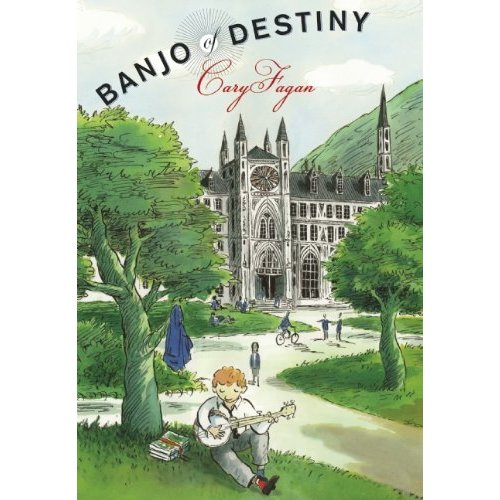

Banjo of Destiny

Authors: Cary Fagan

BANJO

of

DESTINY

CARY FAGAN

*

PICTURES BY

Selçuk Demirel

GROUNDWOOD BOOKS ⢠HOUSE OF ANANSI PRESS

TORONTO BERKELEY

Copyright © 2011 Cary Fagan

First published in Canada and the USA in 2011 by Groundwood Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means

without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic

piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate

your support of the author's rights.

This edition published in 2011 by

Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina

Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto,

ON

,

M

5

V

2

K

4

Tel. 416-363-4343

Fax 416-363-1017

or c/o Publishers Group West

1700 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710

www.groundwoodbooks.com

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Fagan, Cary

Banjo of destiny / Cary Fagan ; illustrated by Selçuk Demirel.

eISBN 978-1-55498-141-0

I. Demirel, Selçuk II. Title.

PS8561.A375B36 2011Â Â Â Â Â jC813'.54Â Â Â Â Â C2010-905898-4

Cover art by Selçuk Demirel

Cover design by Michael Solomon

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing

program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the

Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF).

For Emilio and Yoyo

and Rachel and Sophie

The House Built from Floss

JEREMIAH BIRNBAUM

lived in a house that looked like a medieval castle. It was surrounded by a moat and ten acres of grounds. Swans and ï¬amingos ï¬oated serenely on the water in the moat.

Inside, the house was anything but medieval. There were nine bathrooms, a games room with antique pinball machines, a fully equipped exercise room with an oval track, an indoor pool with a water slide and a hot tub. There was an art gallery with paintings from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, a movie theater, a bowling alley. The floors were heated in the winter and cooled in the summer. Hidden sensors turned on the lights when someone entered a room.

Jeremiah's bedroom suite was on the third floor. It had a grand entertainment center, private bathroom with a lion's-foot bathtub and a separate marble shower stall with stereo speakers built in. There was a refrigerator stocked with drinks, and three walk-in closets (one for casual wear, one for formal attire, and one for toys). The desk where he did his homework would have suited the president of a bank.

From his private turret Jeremiah could look down at the artificial waterfall that fed into the moat. His father had stocked the moat with trout. That way Jeremiah could enjoy the experience of fishing without the disappointment of not catching anything.

Jeremiah's house was built from floss âdental floss. His parents had made their fortune from a dental-floss dispenser that mounted on the bathroom wall. The dispenser used laser light rays and a miniature computer to measure a person's mouth and dispense the precise length of floss required. The deluxe model let a person choose a flavor, such as mint, raspberry, chocolate pecan, heavenly hash or banana smoothie.

It was something nobody knew they needed â until the television and billboard and internet advertisements told them they did.

And if you don't have one in your house yet, well, don't worry. You will soon.

Jeremiah had absolutely everything he could want. He was a very lucky boy, as his parents reminded him every day.

“Not many kids have what you have, Jeremiah,” his father would say. “The most advanced home computer available. A miniature electric Rolls-Royce that you can drive yourself. A tennis court with a robot opponent you can always beat. Do you know how lucky you are?”

“Yes, I do,” Jeremiah said.

He meant it, too. What could a kid like Jeremiah have to complain about?

Absolutely nothing.

â¢â¢â¢

THIS WAS

Jeremiah.

Curly red hair.

Freckles.

Pale skin that burned easily in the sun. (His mother made him wear sunscreen even in the winter.)

A slouch when he walked, even though his father told him to stand up straight. (“Remember, you're a

Birnbaum

.”)

Hands that were always fiddling with restaurant menus, gum wrappers, wax from a dining-room candle.

A total lack of interest in the international dental-floss market.

Jeremiah understood that his parents wanted to give him everything because they themselves had once had nothing. His father, Albert, had worked as a store window cleaner, moving down the street with his long-handled squeegee and his bucket of soapy water. He began work early and he ï¬nished late, but he barely made enough to survive. At night, exhausted, he would look up at the cracked ceiling from the narrow bed in his rented room and dream about finding some way to make his life better.

Jeremiah's mother, Abigail, ran a hotdog cart. She didn't own the cart. She just worked for the man who did, Mr. Smerge. Mr. Smerge complained if her customers used up the condiments. “Too many pickles, too little profit!” he scolded.

At the end of each week, Albert would treat himself to a hotdog for dinner, loading it with pickles, onions, hot peppers and sauerkraut. He thought Abigail had a nice smile, but he was too shy to start up a conversation. Instead, he sat on a bench near the cart and ate his hotdog by himself.

One day Albert felt something caught between his teeth. He tried to work it out with his tongue and then, hoping nobody was watching, with his finger.

When he looked up, he saw the woman from the hotdog cart standing in front of him. She was holding out a little container of dental floss.

Albert said thank you and tore off a piece of floss.

“I've taken more than I need. What a waste, I'm so sorry,” he said.

“That's all right, I do it all the time,” said Abigail. “There ought to be a dispenser that gives you just the right amount, don't you think?”

And that's when Albert's eyes lit up.

Jeremiah had heard the story many times about how his parents had come up with the idea for their invention. How his parents' courtship was spent designing the dispenser. Abigail did the research on laser calculation, computer miniaturization, as well as the dispensing mechanics. Albert learned how to set up a manufacturing operation and distribution network.

Jeremiah understood that his parents had grown up with so little that they wanted only the best for him. But he didn't see why he had to be a “gentleman,” as his father called it. Why he had to know how to shake hands and call people “Sir” and “Ma'am.” Why he had to wait until everyone else was seated before sitting down himself at the dining table.

“You have to know how to behave around rich and powerful people,” his father said. “They expect a certain standard. Especially from children. Your mother and I never learned these things but you will. It's why we insist you take all those lessons. So you will be an accomplished and impressive young man.”

Jeremiah certainly did have a busy after-school program. Every day at four o'clock one teacher or another rang the doorbell. For ballroom dancing. Etiquette. Watercolor painting. Golf. And, of course, piano.

Ballroom dancing made Jeremiah feel queasy. He had to wear a suit with tails and a bow tie. He had to dance around the empty ballroom with a woman old enough to be his grandmother.

“Head up! More manly! Feel the music!”

she would snap at him.

Painting lessons were a little better, not that he was very good at it. He tried to copy a self-portrait by Rembrandt but it came out cross-eyed. His imitation of a landscape by Van Gogh looked like somebody's plate after a spaghetti dinner.

Etiquette was merely boring. He had to pretend to eat a meal without putting his elbows on the table and say, “These snails are delicious.” He got double points off for yawning or rocking his chair back and forth. Playing golf, he broke three windows and clipped Wilson the gardener's ear. Wilson yelped and dropped the garden hose, spraying Jeremiah's father who was bending over to smell a flower.

Worst of all were the piano lessons. Because Jeremiah actually liked music. He listened to his satellite radio all the time â pop, jazz, rap, heavy metal, classic rock. But Jeremiah's piano teacher and his parents insisted that he learn only classical music.

There was nothing wrong with classical music, except that it didn't interest Jeremiah. Maybe if his parents hadn't forced him to appreciate it, he would have liked it more. But instead of going out to play he would have to sit up straight and listen to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony while his mother exclaimed, “Do you hear it, Jeremiah? It's genius, genius!”

Naturally they insisted on piano lessons.

“What do well-bred people do in their spare time?” said his father. “They play classical music on the piano. Isn't that right, Abigail?”

“Absolutely,” said his mother. “It's the sign of a good family. We can't wait to see you in the next school talent night. We're going to be so proud.”

Jeremiah knew he was sunk. If he tried to argue, his father would remind him that he had once washed windows for a living. His mother would tell him again how she had once sold hotdogs.

“My life,” Jeremiah Birnbaum said aloud as he lay on his bed and looked up at the copy of Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel on his ceiling, “is a very expensive nightmare.”