Backstage with Julia (8 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

I don't remember what time we left the cozy dining room at Mercurio's and walked around the corner to our hotel, but I do remember it was after lots of food and wine, and long after Julia had exhausted the restaurant's supply of amaretti wrappers. I was not used to consuming that much alcohol in one night (in college I'd acquired the nickname "Thimble Belly"). I floated, much like the amaretti papers, back to the hotel and fell into bed.

At five-fifteen the next morning, I was no longer floating. As I approached our waiting car, I felt more like the ashes of the previous night's burned-out amaretti wrappers.

Julia, already seated in the back of the car, looked refreshed and eager to get on with the day. Through the fog in my head, I had impressions of having acted somewhat less than professionally the night before, and I wondered if I needed to apologize for anything. Just in case, I said, "I think maybe I had too much to drink last night. I feel as though I was dancing on tables."

She put her hand on my knee and smiled. "You were. But you were very good." I'm pretty sure that was the exact moment that I stopped seeing Julia Child the culinary idol and saw the personâand I really liked her.

Chapter 3

What is the recipe for successful achievement? To my mind there are just four essential ingredients: Choose a career you love, give it the best there is in you, seize your opportunities, and be a member of the team.

âBenjamin F. Fairless, industrialist

When I began to work for Julia, her appearances on

Good Morning America

occupied but a few dates of a full schedule that was at most mind-boggling and at the least . . . well, mind-boggling. Demonstrations, media appearances, and book signings all over the country kept her on the move at a relentless pace, and her time at home was just as busy. In addition to writing a monthly column, with recipes, for

McCall's

magazine, she planned and outlined her programs for live demonstrations and TV shows. Although she often recycled recipes for her demonstrations, tweaking them to fit the time and situation, she liked to develop new ones for print and for TV. Creating and testing recipes takes time. Some ideas that taste good in one's head fail to meet one's expectations when completedâperhaps the derivation of "The proof is in the pudding." Even when the pudding is good, the recipe may need adjustments to make it perfectâa little more sugar, less flour, longer cooking, a different pan. That means retesting, and if that doesn't go just right, testing again, and sometimes again. Once Julia was satisfied that the recipes were exactly as she wanted them, she then spent hours typing them in her impeccably clear and detailed Julia style, wrote headnotes for

McCall's

, and broke down the television and demonstration recipes into scripts and lists of required food and equipment. So when she wasn't on the road, she was usually in her office writing, or up to her apron strings in groceries in her kitchenâone of her kitchens, that is, since she divided her time between her homes in Cambridge, Santa Barbara, and France. In her "free time" she attended national culinary conferences and participated in a slew of professional events at local restaurants and cooking schools.

I don't think the term had entered our vernacular back then, but Julia could have invented it:

multitasking

. And she could have taught classes in how to do it. She had the organizational skills necessary to manage her complex and demanding workload. Moreover, she had the energy, she relished being busy, and, most important, she loved what she was doing. I've no doubt that she could have whisked her way through all that work by herself, but as she said, "cooking together is such fun," so she employed a number of people to share in her good time. Depending on the task, one or a number of assistants joined her on the road or cooked with her in her spacious, slightly funky lime-green Massachusetts kitchen, her smaller but efficient California space, or her charming, quintessentially Provençal

cuisine

.

Even book signings required some assistance, since the crowds were usually too large for bookstore personnel to handle alone. A personal assistant at her side helped move the lines along by passing her the books already opened to the page she would sign. This seemingly minor expediency saved time and allowed Julia to concentrate on her fans until every person had a signature and a word with her, regardless of the fact that the lines inevitably wound out the door and around the block and the signings took hours. Someone recorded the bodies at one signing as fourteen hundred, and Julia stayed until the last smiling fan departed with a book inscribed, "Bon appétit! Julia Child." Of course, authors are expected to stay, but we did all gasp at stories of some who just up and left after a certain amount of time. Julia cared far too much for her audiences to allow them to shuffle slowly through a long line only to be left hanging with unsigned books. Besides, Julia was generally interested in people and loved hearing their stories. Initially I thought she engaged fans in conversation just for the show, but then sometime later in the day, or the week, she'd say something like, "Isn't it remarkable that the woman in the wheelchair went back to college with ten children at home and an infirm father to take care of?" Gosh! I hadn't picked up on that. But as in every crowd, some people just wore out their welcome, and when they lingered a bit too long in front of her, she artfully used her assistant to help graciously shuffle them away from the table. "That's fascinating," she would say to the fan. "Here, now tell [designated assistant] all about that," thereby forcing the lingerer to step out of line and redirect attention to the assistant.

It was at book signings and culinary gatherings that I realized one of Liz Bishop's most valuable assets as an assistantârunning interference. Since Julia believed that it was "part of the job" to speak to each fan who approached her, it was no easy task to get her from one end of a crowded room to the other. Some of those who approached her were friends, and Julia wanted to ask them about their families, or how their books, schools, or new shows were going. Others were strangers, but Julia felt no less need to give them her attention. Talking to everyone was impossible on those occasions when she was on a tight schedule, and that's where Liz came in. The two of them would perfectly orchestrate their moves through a crowd, with Julia smiling but not making eye contact with approaching fans and Liz close at her side, tersely reciting a litany of efficient brush-offs: "We are in a hurry. I have to get her to an appointment. We don't have time. Please let us pass." They did it so well.

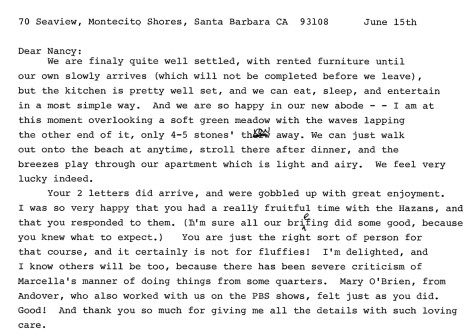

Julia essentially divided her assistants into East Coast and West Coast teams, and for all the years I worked with her, she varied and alternated the team players and their positions. No one ever participated in every Julia event. Sometimes a team member might fly to the working coast, but, being the practical, frugal person she was, she usually employed the person or people geographically closest to the job. In a letter she wrote to me from California a few months after I started at

GMA,

she described classes she had taught at Mondavi Vineyards and referred to Rosemary Manell as "my West Coast Liz." Rosie was more demure than Liz but, at six feet tall, probably more effective at blocking tactics. Since the

GMA

studios were in New York, I was part of the East Coast team. From April through June of 1981, when she suspended her taping until fall, that once-a-month gig and the one demonstration at De Gustibus were the only work I did with herâthe only direct involvement I had in the industry that was Julia Child Productions.

Then, early that summer, Sara was offered a chef's position at the New York restaurant La Tulipe to start the following October. Julia was delighted for her, but she also wondered if Sara would be able to meet the demands of both late-night restaurant and early morning television work, so she promoted me to executive chef and gave me more responsibility for the shows. As it turned out, Sara's restaurant schedule and her energetic personality allowed her to continue working with us at

GMA

until 1984, when she left La Tulipe to work in

Gourmet

magazine's test kitchens. When, in 1987, she became the executive chef for

Gourmet

's dining room, she once again had the flexibility to return to

GMA

. She eventually became the show's regular food editor, a position she still holds today.

"Executive chef" is the title Julia chose, and I have always felt a bit squirmy about using it. Traditionally "chef" refers to someone who works in a professional kitchen or restaurant, and the executive chef is the one in charge. Unlike Sara, I had trained not for restaurant work but for teaching, much as Julia herself had, and I never call myself a chef, nor did Julia. Regardless of the title of her

The French Chef

series, Julia considered and called herself a "cook" and often a "home cook." So I was surprised she used that title for us. Sara explained that years before, while they were working on the PBS television series

Julia Child

&

More Company

, there was a bit of a muddle on the set because no one knew exactly who was responsible for what. Julia thought of her assistants as a team of equals, all Indians and no chiefs, and originally did not create a hierarchy of positions. Sara said it caused confusion, so Julia, master of organization, decided to assign a title to everyone. She named her body of assistants "Julia Child associates" and, most likely for want of a more explanatory term, bestowed the title "executive chef" on the person who would tell everyone else what cooking needed to be done and be responsible for seeing that it was. Julia was pleased with the order the titles gave. Liz was officially "executive associate," and when Rosemary Manell worked as the food stylist and not the "West Coast Liz," she was the "official food designer." An artist with her own quirky sensibilities, Rosie disliked the more common term "food stylist," so she suggested "food designer"; Julia added the "official."