Backstage with Julia (4 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

"You studied with Madeleine?" she asked, raising her eyebrows and tilting her head in the direction of my Modern Gourmet diploma in the bookcase. This was a touchy subject because I knew that there was bad blood between Julia and Madeleine. The times that Madeleine even mentioned Julia in class, it was to say, "She is neither French nor a chef."

"Yes, I did," I responded, and Liz gave me an inscrutable smile. I gave it my own read: I would be condemned by association and deep-sixed before I got to demonstrate my efficiency or serve my great-grandma Feely's red chowder. But no one said anything more on the subject. Not then, anyway.

We spent close to an hour in my kitchen, getting to know each other and smiling for Sylvia, who, being Sylvia, had her camera and was snapping photos. Julia talked mostly about the recipes for the demonstrations, describing in detail how she planned to mix this or assemble that. The words

perfectly, carefully,

and

impeccably

sifted evenly throughout her descriptions, and I knew she was sending me a message:

We don't rush through things.

As she spoke, her hands slowly pantomimed cooking motions, and I remember how their expressiveness captured my attention. Julia had very long, graceful fingers, adorned only by a lovely wide gold Tiffany wedding band. When she was imitating a culinary move, she cupped her palms slightly, tightened her knuckles a bit, and splayed her fingers gracefully in a most distinctive gesture. They were artist's hands, chef's tools that never ceased to captivate me. And her eyes intrigued me. They were the most delicate shade of pale blue and glistened as though tears were waiting to appear.

"The caramel gave us a lot of trouble in the past," she said, referring to the spun-caramel dome that would sit over the cake she was to demonstrate. Although I had never made a caramel dome, I knew the process involved swirling hot caramel with a spoon into a webbed pattern on the exterior of a bowl and, when it cooled, lifting it in one piece off the bowl.

"How so?" I asked, wondering what problems she had encountered.

"It kept breaking when we lifted it off the bowl. We tried different bowls, more butter, layers of plastic wrap. In the end, we found the difference was chilling the bowl beforehand."

It was obvious from her animated discussion that not only had she researched the releasing qualities of caramel with scientific precision, but she had thoroughly enjoyed the research process. It had been thirty-one years since Julia took her first cooking class at the Cordon Bleu, and yet there she was enthusing about learning a technique with the same passion of a first-year culinary student. Her enthusiasm was infectious.

That evening, at the patrons' gala dinner, I met Julia's assistants, Marian Morash and Sara Moulton. My copy of Marian's

The Victory Garden Cookbook

, the landmark, definitive work on vegetables, was as worn and stained as my copies of Julia's books. I had watched her on her own television show,

The Victory Garden

, but I didn't know that she is married to Russ Morash, the director responsible for Julia's successful burst into the television world. Sara, who would go on to become the star of her own shows on the Food Network, is a petite dynamo. I like to call Sara "petite." Since I am only five feet two inches, it's elevating working with someone who's even shorter. Sara looked like a teenager, but I knew she had to be older than that, because it took a lot longer than nineteen years to accumulate her degree of culinary expertise. Since both Marian and Sara had worked with Julia for a number of years and knew her routine well, I expected they would hardly need me for anything more than managing the dishwashing station.

The next morning, I stood back and waited for directions.

"Where should we begin?" Marian asked me. "You're in charge." How generous is that? Marian and Sara intended for me to be the onstage assistant to Julia during the shows, and their instant acceptance of me immediately endeared both women to me.

Julia's demonstration that afternoon was to be devoted to fast puff pastry, a quicker but no less buttery version of the classically made, multilayered flaky pastry known in French as

pâte feuilletée

. The classic version calls for spreading masses of butter over a large sheet of pastry dough,

pâte brisée

, and then folding the two into a package. The butter and pastry package is then rolled and folded, rerolled, and folded again for a total of six times called "turns," with chilling necessary after each turn. Its success depends in great part on the cook's ability to handle the butter so that it maintains the ideal temperature to spread properly through the layers of dough: too cold and shards of it can pierce the dough, too warm and it can ooze out the sides, sticking the dough together and preventing it from separating into flaky layers.

In 1980, we couldn't buy puff pastry in the market, so if we wanted it, we had to make our own. Julia did not invent the faster method, which she called

"pâte feuilletée express

," but she heralded its use to her audiences so that they would not miss the joys of the layered pastry because they found the classic method daunting. With quick puff pastry, instead of a large sheet of butter spread on top of the pastry, diced pieces are added and blended directly into the flour and water in the bowl of a stand mixer. The dough is then ready for the traditional six turns and folds.

Julia would then demonstrate a number of delicious and inventive dishes you could cook up once you had rapidly made the dough. She would demonstrate two types of pithiviers, that wickedly rich, two-crusted tart that oozes sumptuousness: one with a sweet almond paste filling and the other with savory ham and cheese. There would be individual patty shells, called bouchées, and a large vol-au-vent shell.

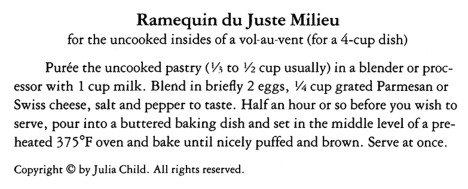

Typically frugal, she also planned to show how to rework any leftover pieces of pastry into cheese appetizers. Then, a

truc

I'd never seen before, she would remove the inevitable bits of uncooked dough from the inside of the baked vol-au-vent, puree them with milk, eggs, and cheese, and bake the lot into a nicely puffed and browned sort of vertically challenged soufflé. She called this last dish Ramequin du Juste Milieu.

All that pastry with its turns and folds, rests, and shaping meant that we were up to our ears in flour and butter with a lot of work to be done before the show, and we all seemed to be in constant motion. Jody Adams, now the award-winning chef of Rialto in the Boston area, was then a young assistant at my cooking school and one member of my team. When I asked her recently what she remembered about those days on the set, she said, "Running. I remember all that running around." This was in no small part because the only water source was the ladies' room, a good distance away from the stage. Julia worked right alongside us, pausing only briefly to take in the aproned army around her and say, "Isn't cooking together fun?"

When Julia took the stage at two o'clock that afternoon, an excited, chattering audience warmed all six hundred seats of the auditorium. The house lights went up; Julia marched onto the stage and was greeted by a great thunderous applause. She clasped her hands together over her heart and bowed her head in appreciation. The clapping went on and on, and she raised her hands above her head and applauded the audience. Gosh, she was some showman. The audience loved it and rewarded her with louder clapping and several whoops.

Finally, Julia took her place at the demonstration counter and we assistants stood at the back of the stage waiting for her call to arms. Liz was perched on a stool off to the side. I realized that Liz was a non-cooking member of the team, a kind of majordomo in charge of Julia's arrangements and appointments. Unless need pressed her into action, she would remain perched. Ruth sat in the front row of the audience with Paul next to her. He held a small stack of handmade signs lettered with numbers on his lap. He was to keep track of the time and hold up a sign to let Julia know how much time she had left.

Assisting in a demonstration is all about anticipating. Good assistants know the recipes by heart, pay attention to the order of presentation, and keep their eyes on what utensils need replacing on the set. We were well on top of things as Julia was whizzing her way through making pastry.

"Ninety minutes!"

Paul Child boomed in a loud voice that startled us all. Then the audience went dead quiet. Heads stretched and turned to see who dared cause such a disturbance. It well might have been an awkward, uncomfortable interruption, but Julia seemed neither uncomfortable nor interrupted. She never missed a roll of the pastry.

"Thank you, Paul," she said, smiling at him, before telling the audience that her husband was keeping time. Just as on the day before, when Paul had scolded me, Julia was not in the least bit embarrassed by his unconventional behavior. She was as unselfconscious and unpretentious in front of an audience as she had been in my kitchen. I had no idea of the years of partnership and romance that went into that simple exchange with Paul, but I saw clearly that Julia had a strong, secure sense of who she was, who they were, and she didn't need to explain or camouflage any odd behavior on or off the stage.

The demonstration continued smoothly, with all of us now nodding our thanks in Paul's direction for his periodic time reminders. When Julia got to the sweet almond Pithiviers, she put the filling ingredientsâsugar, butter, egg, almonds, dark rum, and vanilla and almond extractsâinto the food processor and pulsed them into a paste.

"This has to be well chilled before we put it into the shell to bake," she told the audience as she handed me the bowl. I, in turn, passed it to Brett Frechette, one of the teachers at my cooking school. She was one of the best, a perfectionist. When I handed her the processor bowl, she looked in and whispered to me, "It's separated." I looked down, and sure enough, liquid was seeping out of the paste. It had been mixed too quickly for the flavorings to be absorbed.

"She can't use it like this," Brett said. I looked back to Julia to see if I could return the paste to her for fixing, but she was already on to the next recipe. And I didn't think I should I disturb her by removing the processor from the set.

"The blender," Brett and I whispered at the same time, looking at the brand-new donated Waring blender sitting on one of the workstations. The workstations were long, folding tables that we had swathed in green checked banquet cloths that draped to the floor. Brett grabbed the blender and scooted under the table near an electrical source. I gathered the ingredients and slipped them down to Brett, who turned them into a perfect, firm almond paste to replace the unusable, oozing one. The only person who seemed aware of the quiet whirring emanating from beneath the table was Liz, who smiled at me knowingly from her perch.

The theme for the next night's demonstration was filling and wrapping. The first recipe was an elaborate creation of artichoke bottoms stuffed with mushroom duxelles, topped with poached eggs, napped with béarnaise sauce, and served on a platter with large, homemade croutons. Whew! Then there would be a whole three-pound fish, cleaned and scaled but with head on, cloaked in brioche dough and bakedâFish en Cloak. The grand finaleâand it was grandâwas to be the construction of Mlle. Charlotte Malakoff en Cage, a most elaborate rum-soaked génoise, layered and frosted with a whipped-cream chocolate-hazelnut filling, and haloed with the thoroughly tested, perfectly spun caramel dome. That recipe alone covered five pages, and at the end was Julia's simple, understated instruction to "shatter the dome and cut the cake as usual."