Backstage with Julia (22 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

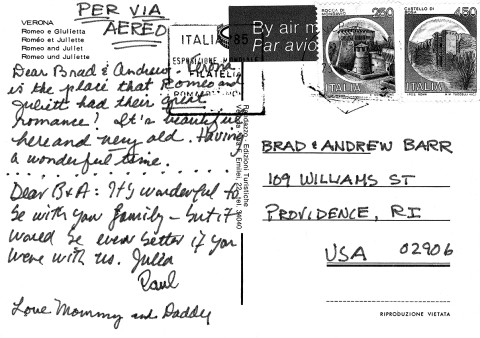

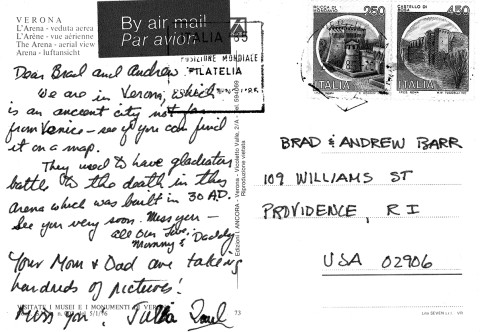

It was more than a mutual passion for food that made me think that Julia would like Nan, Dagmar, and Walter. They all shared deep California rootsâroots that foster a can-do spirit common in many people who trace their heritage to a pioneering spirit. Throughout the trip, whenever a change of plans or spontaneous suggestion came up, it was impossible to tell whether it was Nan, the Sullivans, or Julia who first said, "Why not?"

Walter, who had a way of making such things happen, arranged for us to have balconied rooms at the posh Hotel Danieli directly on the Venice lagoon. Philip and I stayed in a room next to Paul and Julia's, and on our first evening, before we left to go out for dinner, Philip and Julia stood side by side on adjoining balconies to absorb the glorious sites of Venice. It was dusk, and they were standing there just as the multitude of glittering lights came awake along the length of the canal.

"Isn't that magical," Philip said to Julia. "We're so lucky to be here."

"It has nothing to do with luck," she responded. "We work very hard and we've earned this."

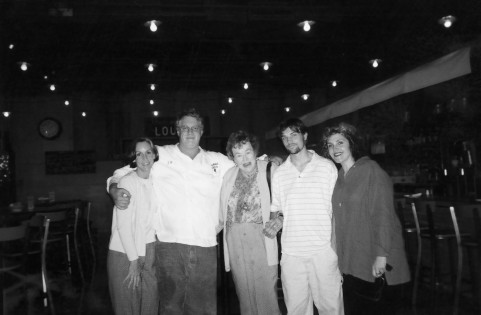

As I suspected, the Sullivans, their friend Ron, Nan, and the Childs took to each other like pasta and

ragù

. One night at dinner, the subject of "crunchily undercooked vegetables," as Julia called them, came up. Italians cook their vegetables until they are cookedâcompletely, through to the center. American chefs, on the other hand, were in the throes of the notion that a quick dip in boiling water or a flash in a hot sauté pan was sufficient cooking. The color stayed bright, but the vegetables were crunchy. "I like my vegetables raw or cooked," Julia said, "but that in-between ridiculousness is inedible. I won't eat them." Dagmar was just as disdainful as Julia was about improperly cooked food, and our discussion of certain chefs' lack of classic technique inspired Dagmar to give a most amusing example. Many years earlier, her father had ordered dinner in the elegant dining room of San Francisco's Huntington Hotel. He chose lamb, and the waiter asked him how he would like it cooked.

The Marquis de Pins directed his very regal visage at him and replied, "As it should be."

Julia loved the story, and at every opportunity she saw for the phrase, she pounded the table lightly with her fist and said, "As it should be," and immediately made that expression a common phrase in the trip's vernacular. At one of Venice's better restaurants, the waiter kept our bottle of white wine off to the side of the dining room and was supposedly keeping an eye on our glasses so he could refill them when necessary. But we were consuming the wine faster than he was keeping watch, and finally Julia said to Walter, "Walter, the wine is pouring like glue." Walter broke into his charming, infectious grin and left the table. Within minutes, waiters placed two bottles of wine in ice-filled buckets by our table, and Julia planted her fist on the table, grinned at Walter, and said, "As it should be!"

At every turn of that trip, Walter was our hero. He was just one of those fun-loving men who delighted in surprising those around him. One night we ate dinner at a small but popular trattoria, Da Ivo. The food was traditional Tuscan, not Venetian, but we were all ready for a change of menu. It was situated directly on the canal, and we sat by a window where we could watch the occasional gondola glide by.

"You know," Julia said, gesturing toward the boat, "that's something we haven't done. We should, though." We all agreed and went back to our meal. With the check paid, we rose and headed to exit at the front of the restaurant. But Walter stopped us.

"This way," he said, leading us instead toward the back. At that point in our trip, we were all ready to follow him anywhere. "Anywhere" in that case was into the kitchen, and one by oneâfirmly supported by a chef or dishwasher on each sideâwe stepped out the floor-length window next to the sink, down a few narrow stone steps, and into two waiting gondolas that glided us back to the hotel. It was probably one of the only times Julia was able to walk through a restaurant kitchen without having to stop and sign autographs. No one knew who she was. They may well have thought that Walter was the star, and for us he was.

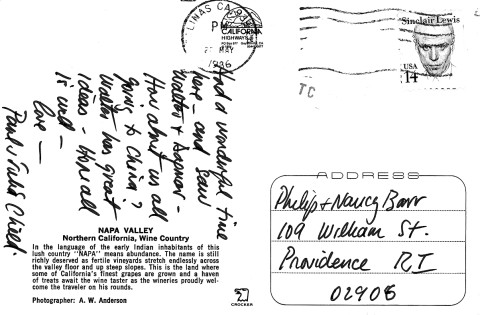

Our Venice trip was such a good time that the following year Julia suggested we join her, Paul, and the Pratts for another Venetian holiday. This time, Philip, the Sullivans, and I said, "Why not?" and that trip, as the one before, was magical. Shortly after we returned home, Julia visited the Sullivans in Napa Valley, and Julia and Walter decided on our next tripâto China. That trip never did happen, but they had a good time planning it.

No question, Julia had a sense of wanderlust. But more than that, she liked traveling abroad because it allowed her to move around out of the celebrity spotlight and just be the wife, friend, and tourist she could never be at home. I can't imagine what a weird feeling it must be to walk around knowing that practically everyone recognizes you. It gives a decidedly literal meaning to Shakespeare's "all the world's a stage." In a play that lasted almost four decades, Julia was always onstage, and she played her part with the understanding that fame is a two-way street. "I fell in love with the public, the public fell in love with me, and I tried to keep it that way," she said in an interview for the

New York Times

. Keeping it that way meant never eating an uninterrupted meal in a restaurant, never shopping for food or bathroom towels or underwear without being asked for her autograph, never having a private moment in a public place.

But in Europe she could be anonymous. Of course, occasionally American tourists recognized her, but so infrequently that it often came as a surprise. On our first trip to Venice, we were sitting at a table upstairs at Harry's Bar, looking over our menus.

"I wonder how the risotto is here," Julia asked.

Before any of us could comment, a voice from the next table said, "It's delicious. Do you want to try it, Julia?" Julia actually looked startled to hear her name come from somewhere other than our table. She turned around to see a young man holding out his own plate of risotto for her to try. She hesitated for a moment, and then she chose to be the Julia that audiences loved. She picked up her fork and dug right in.

Occasionally Julia disregarded her vow to love and be loved. When an American tourist followed her around in a Venice museum, trailed her out of the museum, then finally yelled at her back, "Is that you, Julia?" Julia flatly responded, "No," without stopping or turning. She ignored a fan at London's Heathrow Airport early in the morning after we flew in overnight from Boston and were standing at the end of a very long customs line. A most unattractive, large man was standing at the beginning of the line, and when he looked beyond the many curves in the queue and spotted Julia, he began to shout in an irritating voice, "Julia! Julia! Over here."

Julia looked at her feet and pretended not to hear, but he was relentless and continued to call her name. All up and down the line, heads were turning in our direction. I was used to strangers approaching her, but I realized that morning how absolutely grating it is to have someone call your name repeatedly across a crowded room. It was like being the object of a hazing.

"Stand in front of me so he can't see me," she said.

Was she kidding? Given the difference in our heights, it was impossible to block her, but I hoisted my carry-on onto my shoulder and did my best. It accomplished her goal: the man got the message and stopped yelling her name. If he ceased being a fan, I'm sure Julia couldn't have cared less. There

are

limits, and shouting across a crowded hall is one of them.

Those trips to Venice and the times we shared with family and friends, out of the spotlight, made me realize how very much Julia enjoyed being just one of the gang. That's not to say that she craved anonymity. She enjoyed her fame. Far from being one of those celebrities who only dare to appear on the streets concealed by wigs, strange hats, and oversized sunglasses, she strode about her world undisguised. Somehow, she maintained a balance in her life. No matter how many people recognized her, how many awards she received, or how many books she sold, she remained centered on her true self, not her celebrity persona. At culinary conferences, she always insisted on wearing a name tag, although the people at the registration desks told her she wouldn't need one. "I want one, just like everyone else," she'd say. In reality, of course, she was not like everyone else; she was famous. But she chose not to allow her fame to define who she wasâone of the reasons that Julia herself was more special than her fame ever was.