Backstage with Julia (17 page)

Read Backstage with Julia Online

Authors: Nancy Verde Barr

When it came to food, her curiosity was especially inexhaustible. She planned lunch and dinner parties around local or visiting chefs and cooked the meal alongside them, not only because she found it such fun but because she learned from them. "That's fascinating. Show me how you did that," she'd encourage whenever she saw a technique that was new to her. Playful bickering and differences of culinary opinion aside, she adored working with Jacques Pépin, her dear friend and the ultimate master chef, because the good-natured competition kept her mind agile.

She did not reserve her interest in techniques for chefs. Philip Barr has a most unusual way of eating a fresh pear. He begins by inserting a sharp paring knife straight downward, parallel and close to the stem, until he feels the tip of the knife touch the core. He then removes the knife and makes additional cuts around the stem until he can lift a neat circle of pear out of the top. Then he turns the pear over and slips the knife into the blossom end, angling it out slightly to reach beyond the wider bottom core. He continues making incisions around the core at the blossom end until it is free of the flesh and he can push it out. Then he turns the pear right side up and makes neat horizontal cuts, leaving him with perfect, 1/2-inch-thick, donut-shaped slices. When Julia saw him do this sitting at her kitchen table, she was fascinated. She picked another pear out of the fruit bowl and handed it to Philip. "Here. Do it again. More slowly."

I marveled at her curiosity, and I teased her about it. Once when we were making a simple salad in her kitchen and I said, "We are now going to consider the forty-two or so possible ways to trim and wash a head of lettuce," she came right back at me with, "There are fifty-four ways and I think we should try them all." Mostly I envied it, and I once asked her if she had always had such a keen interest in so many things.

"Not at all," she responded. "It was Paul who taught me to really look at everything around me. When I met him, he thought I was a scatterbrain. And I was." I might think that she was exaggerating, but Paul's assessment of Julia's lack of attention to detail is forever stored in the archives of the Schlesinger Library. Shortly after meeting her, he described her to his brother Charlie in a letter: "Her mind is potentially good but she's an extremely sloppy thinker." Paul made it his mission to correct that, and he obviously did a bang-up job. When he introduced her to the joys of the table, particularly the French table, she found her passion, and with it a sense of direction. With intense curiosity and dogged determination, she spent the rest of her life perfecting her culinary knowledge.

"[Cooking] takes all of your intelligence and all your dexterity," Julia said in a 1984 interview, and she always gave it her all. She wanted to know exactly how things worked, why they didn't, and how many ways they could be made to work. She delved into the origins and uses of ingredients the way Einstein studied relativity. She attacked questions of technique scientifically through research, multiple rounds of testing, and querying authorities.

Those of us who worked with her, especially when she was developing recipes for her cookbooks, became part of the research team. We shared her enthusiasm, but I don't recall that any of us were prepared to approach all subjects with Julia's thoroughness. Hard-boiled eggs come to mind. HB eggs, in Julia-speak, are not something we think of as particularly difficult. Most cooks can and have made them, yet Julia felt they warranted extensive, exhaustive research. To prick or not to prick, how much water, how long to cook to avoid that "dolefully discolored, badly cooked yolk" with its telltale green-hued ring, how to peel, and how to store were all issues to which Julia wanted definitive answers. She tested several methods, contacted a number of authorities, and liked the method suggested to her by the Georgia Egg Board. It was fail-safe but fussy, and few of us were as excited about it as Julia was. First the eggs must be pricked a quarter inch deep in the thick end, then covered with an exact amount of water depending on the number of eggs, brought just to the boil, immediately removed from the heat, covered with the pan lid, and left to sit for

precisely

seventeen minutes. When the time is up, the eggs are transferred to a bowl of ice water and chilled for two minutes, then, six at a time, returned to boiling water for ten seconds, and finally put back in the bowl of ice water to chill for fifteen or twenty minutes before peeling. They were perfect HB eggs and a perfect pain to doâfor everyone but Julia.

Whenever our work called for them, we anxiously looked at each other, hoping someone else would do them. If Julia was out of the kitchen, whoever picked the short straw was always tempted to cook them according to his or her own favorite method. The one time she caught me using my technique instead of hers, she didn't tell me to stop, didn't insist I use hers. She cautioned me with one of her favorite warnings: "When all else fails, read the recipe."

Turkey received the same thorough research as HB eggs. At some point in the eighties, high-heat roasting became the in technique. Magazines and cookbooks devoted a considerable number of pages to the procedure, purporting to tell the reader "everything you ever wanted to know about roasting"âunless you were Julia Child.

"I think we should test all these methods," she said to me over the phone one day in July. "Would you get five turkeys and roast them five different ways? I'll do the same and we'll compare results." She was particularly interested in the best way to roast poultry since there is always the problem of having the dark meat fully cooked without the white meat drying out.

So for several days, as the temperature stubbornly hovered at record-high levels, I cooked turkeys in my un-air-conditioned summer homeâone after the other, because I had only one oven. I roasted one at a moderate 325°F, another at a frightening 500°F. I started turkeys three, four, and five at one temperature and finished them at another. Julia called me midway through her testing.

"Well, the 500°F turkey smoked up the whole house!" she reported. "And the oven was a horrid mess. The meat was juicy but I think a bit tough. I'm going to try it again and reduce the heat after the initial browning. Maybe add some water to the pan. What did you think?"

What I thought was that no one should roast anything when the oven and the kitchen are at the same temperature! In the end, she continued to cook her turkeys as she had always done, at a steady 325°F, but she was satisfied in knowing exactly what each method would produce. Meanwhile, I couldn't get anyone in my family to eat roasted turkey for months. At Thanksgiving, they begged for roast beef.

Cooking, when approached Julia's way, was without question the serious discipline she said it was. It required time, thoroughness, and impeccable attention to detail. We worked hard, and she worked hard right alongside us. She could have given us a list of chores and taken off to lounge in her roomâwho would have called it bad form? But she loved nothing more than being in the thick of all that chopping, sautéing, whisking, and testing. And that's where the fun came in, because Julia was Julia.

Multitasker that she was, when we were working at her Cambridge home, she'd put the kitchen phone on speaker and deal with necessary business at the same time she was cooking. When someone called, she'd introduce the phone person to the kitchen peopleâ"Now say hello to Nancy, Marian, and Liz"âand she'd expect us to engage the faceless voice in conversation. When the voice belonged to one of her favorites, we'd be privy to delightful exchanges such as her sign-off to Cuisinart founder Carl Sontheimer, "Give yourself a big, wet sloppy kiss for me," and his to her, "An even wetter, sloppier one back to you."

When she wanted a more private conversation, she didn't leave the kitchen. She'd sit on the stool in the corner and pick up the receiver. The one-sided conversations we heard were no less engaging. When her friend and lawyer Bob Johnson was in the hospital, Julia called him often. One day as Susy Davidson and I cooked, Julia sat on the stool, picked up the phone, and dialed the hospital. "Robert Johnson's room, please," we heard, and then, after a pause, "Hi, Bob, it's Julia." There was another very brief pause and then Julia said she was sorry to have disturbed the person. She hung up, dialed again, told the answering party that she had been given the wrong room, and again asked to speak to Bob. This time she knew right away that the person who answered was not Bob because she immediately said she was extremely sorry and called the hospital switchboard a third time. Amazingly, the mix-up occurred again, but this time we heard her say, "Well, I'm awfully sorry that I have bothered you again. I was trying to reach a friend who is there also. But tell me, how are

you

?" She spoke to the unknown patient for at least five minutes, and Susy and I had to leave the room to prevent our giggling from disturbing the call.

Working with Julia on her projects provided all the professional stimulation I thought I needed, but she was not about to let me make a career just being a Julia Child associate. Even during those periods when our work together was time-consuming and extensive, she encouraged me to continue with my own work. She suggested classes for me to take, introduced me to people I should know, and brought me out front onstage with her to give me exposure to her audiences. And, for which I am so very grateful, she encouraged me to write.

"It's publish or perish," she told me about a year after I began working for her. We were riding in the car on a long trip somewhere and talking about college. She told me that when she went to Smith she'd intended to be "a great novelist," but when she graduated and applied for a job at the

New Yorker

, "they had no interest in me whatsoever." After trying

Newsweek,

she finally got a job in public relations and advertising for the W. & J. Sloane furniture store in New York. Eventually, of course, she achieved success as a writer; cookbooks were her novels. And she was a fine writer, with a full, colorful vocabulary, meticulous attention to grammar and syntax, and an enviably natural way of expressing her thoughts. She was careful about her text and fluently descriptive with her recipes.

During that ride, after she told me her college story, I told her mine. I had also aspired to be a writer, althoughâtypical of the differences in our personalitiesâI'd never thought "great novelist," simply "writer." My aspirations were sideswiped not by the

New Yorker

but by a classmate in my junior year. We were in Mr. Taylor's creative writing class and one by one we had to read essays we wrote. When the boy sitting next to me read his, I had an epiphany, and not a good one.

He's a writer,

I said to myself.

I'm not.

That boy was Tom Griffin, who went on to be a noted playwright

(The Boys Next Door

,

Einstein and the Polar Bear)

. Had Julia been my friend back then, she would never have allowed me to give up my dream just because someone else was better at what I wanted to do.

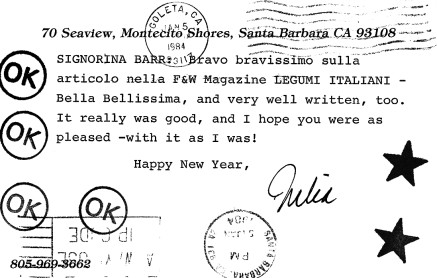

After that conversation, she began to encourage me to send articles to culinary magazines. I did, and when I proudly announced that I had sold my first one to

Food

&

Wine

magazine, she said to send more, to all the magazines.

Gourmet, Cook's Illustrated,

and

Bon Appétit

bought my articles, and as soon as the issues arrived at her door, she called or wrote to tell me how much she enjoyed what I had written.

When I told her of an idea I had for a book, she wrote back: "Glad you got through your last classes and that you are really in there writingâthat's the way to do it. Yes, for the bookâbut get lots done first so you'll have something to show, including a complete outline for all of it. The illustrations sound good and original. (We rewrote our Mastering I three or four timesâso never get discouraged whatever happens.)"

It was three years before I decided I was ready to propose the book. I got "lots of it done," as Julia suggested, included a "complete outline," and sent it to an agent in spite of the fact that many friends suggested I ask Julia to show it to her editor at Knopf, Judith Jones. But by the time I was ready to pitch my book, I had learned an important fact about Julia. She did not lend her name easily, did not write forewords or blurbs for other people's books. Unless she herself had tested every recipe in that book, she wasn't going to imply approval of it by having her name associated with it. Companies asked her constantly for endorsements, and she always said flat out, "No. How do you know that company will still be good in six months? If it goes downhill, my name goes with it."

So completely did I understand and respect that about her that I never considered asking her even to suggest to Judith that I might be able to write a book. Suppose I couldn't? Then Julia would be barreling down a hill with me. Since Julia's lawyer negotiated her contracts, she never used an agent and couldn't recommend one. Cookbook author Jean Anderson generously loaned me hers, Julie Fallowfield, and ironically, the first publishing house Julie pitched was Knopf. And it wound up being the only one she pitched, since Judith bought it. Julia was thrilled, not only that I had sold the book but that I would be working with Judith. "None better," she said as she opened a bottle of champagne to toast my success. That was the celebrating part of the book, the part before the actual dogged work of writing it.