B004R9Q09U EBOK (23 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

Well into the eighteenth century, most European households owned at most a single book, often a popular devotional text like the

Book of Hours

. Merchants might keep a small private bookshelf with a few volumes, while scholars and clergy might maintain slightly larger private libraries. There was no such thing as a public library. For all the expansion of publishing, most people could not afford many books; they were still expensive commodities. In such a constrained market, the idea of a book culled from other books held out a tantalizing value proposition.

As printed books continued to proliferate across Europe, authors and publishers started to expand their ambitions. By the eighteenth

century a few scholars, inspired in part by Bacon’s quest for a unifying philosophical framework, had started to pursue the idea of a great “universal” encyclopedia. History’s greatest encyclopedist was Denis Diderot, a Frenchman who adopted Bacon’s classification as the foundation for his monumental

Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers

(“Encyclopedia or Dictionary of the Sciences, the Arts, and the Professions”), published in a succession of volumes from 1751 to 1772. A massive collection of 72,000 articles written by 160 eminent contributors (including notables like Voltaire, Rousseau, and Buffon), Diderot created a compendium of knowledge unrivaled in any previously published work.

The new encyclopedia was more than just a collection of previously published scholarship. Diderot took the unprecedented step of trying to capture folk knowledge from common tradespeople, devoting an enormous portion of the encyclopedia to knowledge about everyday topics like cloth dying, metalwork, and glassware, with entries accompanied by detailed illustrations explaining the intricacies of the trades. The encyclopedia gave folk knowledge roughly equal billing with the traditional domains of literary inquiry: scripture, scholarship, and politics. While publishing this kind of “how-to” information may seem unremarkable today, in the aristocratic literacy culture of eighteenth-century France such a mingling of high and low cultures constituted a blunt political statement. By granting craft knowledge a status equivalent to the high written culture of statecraft, scholarship, and religion, Diderot took a epistemological step toward revolution. At the time, most lower-class people remained illiterate, and whatever trade knowledge they held still passed primarily through the close-knit social networks of family traditions, apprenticeships, and trade guilds. Almost none of that information had ever been recorded, and even if it had, it certainly would have held little or no interest for the powdered-wig habitués of Parisian literary salons. In according tradespeople such respect, Diderot was sounding a clarion call in favor of the common worker.

Today, we may find it difficult to imagine how the act of publishing information about cloth dying could possibly foment political upheaval. In eighteenth-century France, however, Diderot’s work

caused enormous consternation among the privileged classes. Pope Clement XIII castigated the work. King George III of England and Louis XV of France also condemned it, anticipating the political consequences of providing the common folk with such easy access to knowledge that had previously been sealed away. In 1759 the French government ordered Diderot’s publisher to cease publication, seizing 6,000 volumes, which they deposited (appropriately enough) inside the Bastille.

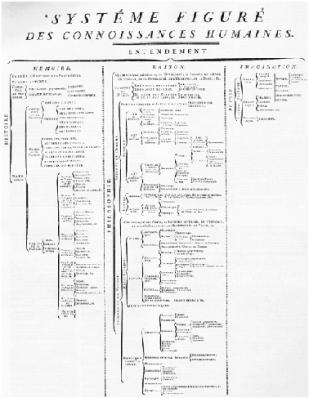

Outline of Diderot’

s Encyclopédie.

Diderot died 10 years before the revolution of 1789, but his credentials as an Enlightenment encyclopedist would serve his family well in the bloody aftermath. When his son-in-law was imprisoned during the revolution and branded an aristocrat, Diderot’s daughter pleaded with the revolutionary committee, citing her father’s populist literary pedigree. On learning of the prisoner’s connection to the great encyclopedist, the committee immediately set him free.

9

Diderot’s

Encyclopédie

provides an object lesson in the power of printed texts to disrupt old political and religious hierarchies. In synthesizing information that had previously been dispersed in local oral traditions and craft networks, he created a new system that challenged old aristocratic assumptions about the boundaries of scholarship. Just as the networked movement of the French Revolution was powered in large part by the free flow of documents through the revolutionary social network, Diderot drew on the networks of folk expertise to craft a new kind of book that presented an epistemological challenge to the aristocracy.

Today, the encyclopedia is reemerging as a disruptive information technology. In recent years the Wikipedia project—a Web-based encyclopedia that allows anyone to publish and edit entries—has sparked a fervent debate in scholarly circles. With more than three million entries in more than 100 languages, it is already far larger than any other encyclopedia ever created. Wikipedia’s success has sparked a heated controversy in traditional academic and publishing circles. Questions of authority and credibility inevitably swirl around it. Critics argue that Wikipedia’s lack of quality controls leaves it vulnerable to bias and manipulation, while its defenders insist that openness and transparency ensure fairness and ultimately will allow the

system to regulate itself. There also seems to be a deeper tension at work, between traditional forms of top-down editorial authority and the bottom-up ethos of the Web. Like Diderot’s

Encyclopédie

, the Wikipedia is stirring tensions between established interests—academic scholars and publishers—and a rising populist sentiment. While Wikipedia is unlikely to spell the demise of traditional scholarship, it serves as a telling example of the power of “books about books” to challenge existing institutional systems. The Web, like the printing press, seems poised to augur long-term social and political transformations whose effects we are only beginning to anticipate. And once again, the humble encyclopedia may prove the most revolutionary “book” of all.

Three hundred years after Gutenberg, the printing press had permanently altered Europe’s social, political, and intellectual landscape. Ever since Luther posted his theses on the church door, the spread of printing had left a trail of upheaval in its wake. Popular literacy put an enormous strain on old institutional hierarchies. The Vatican had lost its iron religious and political grip, the French government had fallen, and England and Scotland were feeling the first rumblings of the Industrial Revolution. Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, the printing press had provided the essential platform for the world’s first “document nation”

10

: the United States. The Gutenberg revolution had fomented widespread political upheaval around the world.

For scholars, the old monastic ways had fallen into disrepute, and learned readers struggled to develop new secular frameworks to contain the growing sprawl of published knowledge. Despite the best efforts of Renaissance philosophers and encyclopedists, the volume of printed information was outstripping the ability of any one system to keep up, as a burgeoning collection of books and manuscripts threatened to overwhelm all available ontologies. By the end of the eighteenth century, the problem would come to a head in the domain where it all began: taxonomy.

Ay, in the catalogue ye go for men;

As hounds, and greyhounds, mongrels, spaniels, curs,

Shoughs, water-rugs and demi-wolves, are clept

All by the name of dogs: the valued file

Distinguishes the swift, the slow, the subtle,

The housekeeper, the hunter, every one

According to the gift which bounteous nature

Hath in him closed.

Shakespeare,

Macbeth

In 1787 Thomas Jefferson took delivery in his Paris hotel of the complete skeleton, skin, and antlers of a 7-foot-tall American Moose. The moose had journeyed across the Atlantic, packed in salt, and then traveled overland from Le Havre to Paris in a horse-drawn wagon. By the time it arrived at Jefferson’s hotel, the animal was in sorry shape. Its skin was sagging, and its hair was falling out. But the thing would serve its purpose well enough. Jefferson, then in Paris as ambassador to France, arranged to have the decomposing quadruped placed on public display in the front entrance to his hotel.

1

Parisians flocked to see the strange spectacle. Jefferson hoped that one particular Parisian—the famous Comte de Buffon—would take note of his specimen.

With this curious stunt, the sage of Monticello cast his vote in a raging scientific debate then captivating Europe’s intellectual class. The problem of reconciling the New World with the Old, as we will see shortly, led to a wave of scientific conflicts that would reverberate for centuries. The moose marked Jefferson’s entrée into a taxonomic feud that would have lasting consequences for the future of science,

shaping the trajectory of worldwide information systems for centuries to come.

To understand the importance of Jefferson’s moose to the subsequent history of information science, we must step back 50 years to early eighteenth-century Sweden, where in 1735 a young botanist named Carolus Linnaeus published his landmark

Systema Naturae

, a treatise on the classification of plants. Pursuing his lifelong passion for plant life (as a child he had been nicknamed the “little botanist”), Linnaeus had pursued an ambitious program of collecting information about the plant world and proposing a new systematic framework for describing the natural world, based on his own private studies and on his firsthand experience documenting new plant life while working with the Royal Society of Science. From this project Linnaeus would emerge as the “father of taxonomy,” the first scientist to propose what we would now consider a modern biological classification system.

The eighteenth century was a period of intense research and discovery in the natural world, with scholars discovering thousands of new plants each year. The spread of printing and the rise of the scientific method had fueled a boom in scholarly publishing, as biologists (or “natural historians,” as they would have called themselves) found the means to share their findings with a growing audience of scholarly peers. Cataloging and sharing their observations, eighteenthcentury biologists began to create their own idiosyncratic systems to organize their findings. Absent a unifying conceptual framework, however, much of that work was effectively wasted. Scholars communicated with each other through a vast ad hoc network, publishing books and treatises as they discovered and cataloged new plants in a vast scientific free-for-all. Students of the natural world lived in a Babel of varying naming conventions, assigning Latin words to animal species almost entirely at random. Those names changed frequently as manuscripts changed hands. The hippopotamus—an animal that almost no Europeans had actually seen—went variously by the names river horse, sea horse, behemoth, river paard, and water elephant.

2

And those were just the English names.

The lack of a common classification system made it all but im

possible for scientists to build on each other’s work. Instead, each scientist labored in a kind of personal echo chamber. Recognizing the problem, philosophers over the years had proposed several attempts at universal classification systems. Joseph Pitton de Tournefot grouped 10,000 species into 689 natural genera. English naturalist John Ray sorted all known plant species into two groups—monocots and dicots. Some naturalists preferred to use Conrad Gesner’s sixteenth-century classification. But none of these systems ever caught on.

By the eighteenth century, publishers were turning out numerous works about the natural world. As naturalists clamored for attention from the growing public readership, the problem of classification was coming to a head. To make matters worse, a stream of fresh data was pouring in from the New World. Travelers were returning from the European colonies with reports of new plants and animals hitherto unheard of: corn, squash, beans, tobacco, tomatoes, cranberries, strange new animals like bison, and variations on existing species like the aforementioned moose. There was even a new “species” of New World human beings to contend with: Where did they fit into the tree of life? European naturalists struggled to make sense of the New World.

Linnaeus’s

Systema Naturae

articulated a simple but powerful system for classifying living things. The system turned on a nested hierarchy, consisting of top-level kingdoms, which in turn were divided into classes, orders, families, genera, and species. For example, within the plant kingdom he identified 24 classes, each grouped according to the characteristics of the plants’ stamens. Every class was subsequently divided into 65 orders, based primarily on the number and orientation of its pistils. Ultimately, his system would encompass more than 7,700 plant and 4,400 animal species.