B004R9Q09U EBOK (21 page)

Authors: Alex Wright

While history has remembered Bacon as one of the forebears of the scientific method, he did not envision himself as a “scientist” (the term did not yet exist). Rather, Bacon thought of himself as a natural philosopher, or even as a “magician.” In the medieval sense of the term, a magician was not a conjurer or sleight-of-hand artist but an explorer of the phenomenal world, devoted to exploiting the laws of nature for practical use. Bacon practiced alchemy and saw no conflict between practicing magic and looking for empirical methods. “Toward the effecting of works,” he wrote, “all that man can do is put together or part asunder natural bodies. The rest is done by Nature working within.”

24

In this sense, magic is just another word for science. Elsewhere, Bacon wrote that “[t]he aim of magic is to recall natural philosophy from the vanity of speculations to the importance of experiments.” The duty of a philosopher, as Bacon saw it, was not to reject magical traditions out of hand but to delve into them with fresh eyes and a critical perspective. “For although such things lie buried deep beneath a mass of falsehood and fable, yet they should be looked into for it may be that in some of them some natural operation lies at the bottom.”

25

By invoking the power of observation to sift nature’s truth from the “vanity of speculations,” Bacon forged a new path of understanding the natural world, based not on faith in a divine truth but on the power of individual perception. He rejected monastic scholasticism as a form of mysticism that placed undue faith in divine revelation, preferring instead to trust the individual’s powers of observation; Bacon belonged squarely to the Age of Reason. In 1620, Bacon introduced his most famous formulation of this new way of knowing in his greatest work, the

Novum Organum

.

26

Here he proposed nothing less than restructuring the enterprise of scholarship. The book laid the philosophical foundations for a process that would later become known as the scientific method, a radical departure from the scholasticism that sought pathways to truth through esoteric practices and belief in disembodied ideals. Bacon believed in the capacity of direct perceptual observation to reveal God’s truth, rejecting appeals to external authorities like classical authors or even the scriptures. “I have taken all knowledge to be my province,” he wrote—with no small

display of authorial hubris—staking out an ambitious philosophical agenda in the form of a six-part approach to investigating the natural world.

The title page opens with a grand illustration depicting the words of the title rising above two ships sailing between the pillars of Hercules, symbolizing the limits of human knowledge in the ancient world. By invoking “the pillars of fate set in the path of knowledge,” Bacon signaled his ambition to explore an entirely new kind of knowledge.

The book is an intellectual tour de force, a sweeping foray into a new mode of reasoning that would ultimately fulfill Bacon’s ambition and reshape the trajectory of Western scholarship. Bacon proposed a new method of reason based on induction—reasoning from direction observation—and relying on an idealized system of scholarly collaboration that viewed knowledge as a cumulative enterprise. In other words, he favored networked communication between scholars over received top-down hierarchical modes of understanding, be they classical or ecclesiastical. “I do not endeavor either by triumphs of confutation, or pleadings of antiquity, or assumption of authority, or even by veil of obscurity, to invest these inventions of mine with any majesty,” he wrote. Instead, he aspired to “present these things naked and open, that my errors can be marked and set aside before the mass of knowledge be further infected by them; and it will be easy also for others to continue and carry on my labours.”

27

His vision of research as a collaborative process, subject to trial and error—rather than as the revelation of divine truths—marks the earliest expression of what we now recognize as the scientific method.

For all his belief in collaborative networks of scholarship, however, Bacon was no populist. He frequently voiced undisguised contempt for the common man, believing that the great uneducated masses posed a severe threat to the integrity of scholarship. Paradoxically, Bacon at once advocated the democratization of scholarship while espousing intellectual elitism. He believed that in order to achieve trustworthy results, scholars had to work to overcome the inherent human limitations that keep the majority of the population in the figurative dark. Bacon described these barriers to understand

ing as “idols,” which he described as “the profoundest fallacies of the mind of Man” that spring “from a corrupt and crookedly-set predisposition of the mind.… For the mind of man … is rather like an enchanted glass, full of superstitions, apparitions, and impostures.

28

Bacon’s idols include:

•

Idols of the Cave.

The problem of subjectivity. Each of us inhabits “a cave or den of his own, which refracts and discolors the light of nature.” Our personal biases will always taint our perceptions. We might today say that the chemist sees chemistry in all things; the student of literature looks for narratives; the computer programmer looks for operable rules. Relying on our individual faculties alone can only lead us to imperfect, idiosyncratic versions of reality.

•

Idols of the Tribe

. The problem of human limitations. These are the inborn perceptual constraints of our human “tribe.” He wrote, “human understanding is like a false mirror, which, receiving rays irregularly, distorts and discolors the nature of things by mingling its own nature with it.” We cannot, for example, perceive the full spectrum of colors and sounds; but through the careful application of logical reasoning we can begin to compensate for our sensory limitations.

•

Idols of the Marketplace

. The problem of socially constructed meaning. Our understanding will always be warped by the vagaries of human language. “It is by discourse that men associate, and words are imposed according to the apprehension of the vulgar. And therefore the ill and unfit choice of words wonderfully obstructs the understanding.” Words are imperfect vessels, pale approximations of direct experience.

•

Idols of the Theater

. The problem of belief. Mythologies, religious stories, or ideological convictions present enormous obstacles to understanding, like “so many stage plays, representing worlds of their own creation after an unreal and scenic fashion.”

Only by renouncing received wisdom and superstitious beliefs, and refusing to take anything on faith, can we cultivate any hope of seeing things as they are.

Bacon’s idols constitute a sweeping rebuke of the old medieval mind-set, predicated as it was on “superstitious” belief in the Word of God or the classical ideal of Truth. Bacon argued that the pursuit of scientific truth must be derived from direct observation of phenomena and a process he famously dubbed “induction,” which requires meticulous observation and logical reasoning. In contrast to Aristotle’s top-down system of ideal forms stemming from disembodied conceptual hierarchies (his Great Chain of Being), Bacon proposed a radical new system through which hierarchies of meaning emerged from the bottom up, through the collective effort of scholars creating conceptual building blocks of observed phenomena.

Bacon took an active and hopeful view of human agency, believing that the pursuit of empirical knowledge was a vehicle for human salvation. “Let us hope,” he wrote, “that there may spring helps to man, and a line and race of inventions that may in some degree subdue and overcome the necessities and miseries of humanity.”

29

Ultimately, Bacon’s guiding philosophy was a steadfast conviction that “useful knowledge”—rather than the idealistic pursuit of Truth—would lead to humanity’s salvation.

Bacon’s pursuit of an empirical method would eventually lead him to formulate a new philosophical framework for classifying all of human knowledge. He postulated that all human intellectual pursuits revolve around three essential facilities: memory, reason, and imagination (or, in more familiar terms: history, philosophy, and poetry). Bacon hoped to expound on this framework in his great unfinished work

Instauratio Magna

. Nonetheless, this simple model would also prove to be one of Bacon’s enduring legacies, influencing the thinking of information scientists for centuries to come. As we will see in later chapters, Diderot would embrace Bacon’s scheme as the foundation for his great encyclopedia; Jefferson would later adopt it as the basis for organizing his own personal library, the foundation for the Library of Congress; and Melvil Dewey would acknowledge it as an influence on his decimal system.

For all of Bacon’s subsequent historical impact, in his day his work met with a largely muted reception. His chief patron, King James I, appraised his work with a royal backhanded compliment, noting that he found his lord chancellor’s work—like the peace of God—“passeth all understanding.” Bacon acknowledged the density of his work, likening his undertaking to guiding readers through a “labyrinth.” He never tried to sugarcoat the difficulty of finding a path to true understanding, an effort “presenting on every side so many ambiguities of way, such deceitful resemblances of objects and signs, natures so irregular in their lines, and so knotted and entangled,” that the steps of the true method “must be guided by a clue,” which Bacon envisioned as “a more perfect use and application of the human mind and intellect.”

30

On January 11, 1666, the great English diarist Samuel Pepys wrote of meeting with the well-known London bishop Dr. John Wilkins. Pepys had heard that Wilkins was working on an ambitious scheme to develop a “Universall [sic] Language,” a new way of cataloging human knowledge. Wilkins had invited Pepys to contribute his knowledge of naval matters to the project, and Pepys eagerly answered the call. So too did many other prominent members of the newfound Royal Society, under whose auspices Wilkins had undertaken his project. John Ray assisted “in framing his Tables of Plants, Quadrupeds, Birds, Fishes &c. for the User of the universal Character.” Other notable collaborators included botanist Robert Morison, naturalist Francis Willughby, and clergyman William Lloyd.

31

While the system would ultimately bear Wilkins’s name, it was largely a collaborative effort.

In 1668 Wilkins published his landmark

Essay Toward a Real Character and a Philosophical Language

. Weighing in at a prodigious 454 folio pages, the

Essay

is divided into four sections: an introduction, the tables of “Universal Philosophy” that comprise the bulk of the work, the grammar of a new philosophical language, and finally a section explicating how the character and language work together. In the Universal Philosophy, Wilkins proposes classifying the phenom

enal world into 40 basic categories, beginning with two top-level divisions—“General or universal notions,” and “Special” things—which are then divided into 40 categories (see

Appendix A

for a complete list of Wilkins’s categories). These categories are then subcategorized by “differences” and further by individual “species,” for a total of 4,194 possible classifications. The system works by generating four-letter names based on the rules of the classification: the first two letters corresponding to the genus, the third letter (always a consonant) identifying the difference, and the fourth letter (always a vowel) identifying the species. For example, the genus

Zi

signifies “beasts”; within which the difference

p

refers to “rapacious dog-like beasts” (including, for example, both wolves and dogs); within which the final signifier

a

identifies the particular species, “dog.” Thus,

zipa

means “dog.”

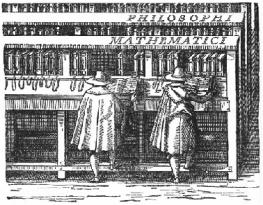

Two Dutch scholars in the library of the University of Leyden, circa 1610, from William Andrews’s

Curiosities of the Church: Studies of Curious Customs, Services and Records

(1891).

In an age of burgeoning secular scholarship, Wilkins believed the world desperately needed a new synthetic language capable of containing the growing surfeit of available data. He thought that the world’s old natural languages had degenerated, becoming “inartificial and confused,” and were poorly suited to accommodate the truth of God’s creation. Older languages, he believed, were fundamentally flawed because of their haphazard development, by “that Curse in the Confusion of Tongues” that left them bedeviled with redundant and imprecise meanings. Like Bacon, Wilkins believed that human comprehension was limited by our preconceived notions about things (cf. Bacon’s “Idols of the Marketplace”). To remedy the shortcomings of written languages, he set out to formulate a new system capable of describing such “natural truths as are to be found out by our own industry and experience,” untainted by existing linguistic biases. As Wilkins scholar Rhodri Lewis puts it, “Wilkins believed that it was possible accurately to map the order of thought (and therefore of the things which this represented), and that it was possible to devise a language which might represent this.”

32

To that end Wilkins set out to create a language “that should not signifie

words

, but

things

and

notions

.” His classification, he hoped, would provide “a sufficient enumeration of all such things and notions, as are to have names assigned to them, and withal so to contrive these according to their order, that the place of everything may contribute to a description of the nature of it.”

33