B0041VYHGW EBOK (61 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

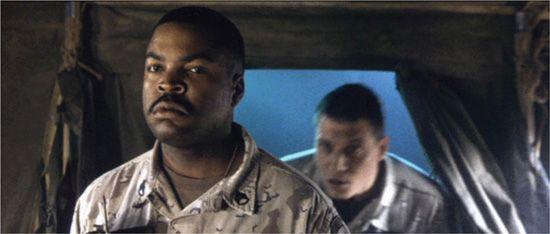

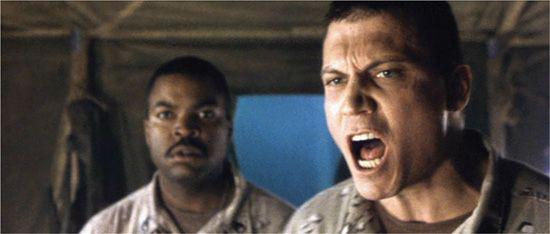

4.149 Confirming Elgin’s warning, the superior officer bursts into the background.

4.150 The officer comes forward, which is always a powerful way to command the viewer’s attention. He moves aggressively into close-up, ramping up the conflict as he demands to know where the men got alcohol.

The

Dying Swan

and

Three Kings

examples also illustrate the power of

frontality.

In explaining one five-minute shot in his film

Adam’s Rib,

George Cukor signaled this. He remarked how the defense attorney was positioned to focus our attention on her client, who’s reciting the reasons she shot her husband

(

4.151

).

Katharine Hepburn “had her back to the camera almost the whole time, but that had a meaning: she indicated to the audience that they should look at Judy Holliday. We did that whole thing without a cut.”

4.151 In

Adam’s Rib,

the wife who has shot her husband is given the greatest emphasis by three-point lighting, her animated gestures, and her frontal positioning. Interestingly, the exact center of the frame is occupied by a nurse in the background, but Cukor keeps her out of focus and unmoving so that she won’t distract from Judy Holliday’s performance.

All other things being equal, the viewer expects that more story information will come from a character’s face than from a character’s back. The viewer’s attention will thus usually pass over figures that are turned away and fasten on figures that are positioned frontally. A more distant view can exploit frontality, too. In Hou Hsiao-hsien’s

City of Sadness,

depth staging centers the Japanese woman coming to visit the hospital, and a burst of bright fabric also draws attention to her

(

4.152

).

Just as important, the other characters are turned away from us. It’s characteristic of Hou’s style to employ long shots with small changes in figure movement. The subdued, delicate effect of his scenes depends on our seeing characters’ faces in relation to others’ bodies and the overall setting.

4.152 Although she is farther from the camera, the woman visiting the hospital in

City of Sadness

draws our eye partly because she is the only one facing front.

Frontality can change over time to guide our attention to various parts of the shot. We’ve already seen alternating frontality at work in our

L’Avventura

scene, when Sandro and Claudia turn to and away from us (

4.110

,

4.111

). When actors are in dialogue, a director may allow frontality to highlight one moment of one actor’s performance, then give another performer more prominence

(

4.153

,

4.154

).

This device reminds us that mise-en-scene can borrow devices from theatrical staging.

4.153 In a conversation in

The Bad and the Beautiful,

our attention fastens on the studio executive on the right because the other two characters are turned away from us …

4.154 … but when the producer turns to the camera, his centered position and frontal posture emphasize him.

A flash of frontality can be very powerful. In the opening scene of

Rebel Without a Cause,

three teenagers are being held at the police station

(

4.155

).

They don’t know one another yet. When Jim sees that Plato is shivering, he drunkenly comes forward to offer Plato his sport coat

(

4.156

,

4.157

).

Jim’s frontality, forward movement, bright white shirt, and central placement emphasize his gesture. Just as Plato takes the coat, Judy turns and notices Jim for the first time

(

4.158

).

Like Claudia’s sudden turn to the camera in our

L’Avventura

example, this sudden revelation spikes our interest. It prepares us for the somewhat tense romance that will develop between them in later scenes. Overall, the scene’s setting, lighting, costume, and staging cooperate to develop the drama.

4.155 Mise-en-scene in the widescreen frame in

Rebel Without a Cause.

4.156 Jim comes forward, drawing our attention and arousing expectations of a dramatic exchange.

4.157 Jim offers Plato his jacket, his action centered and his brightly lit white shirt making him the dominant player. Judy remains a secondary center of interest, segregated by the office window but highlighted by her bright red coat.

4.158 Judy turns abruptly, and her face’s frontal position signals her interest in Jim.