B0041VYHGW EBOK (35 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Now consider the plot of Howard Hawks’s

The Big Sleep.

The film begins with the detective Philip Marlowe visiting General Sternwood, who wants to hire him. We learn about the case as he does. Throughout the rest of the film, Marlowe is present in every scene. With hardly any exceptions, we don’t see or hear anything that he can’t see and hear. The narration is thus

restricted

to what Marlowe knows.

Each alternative offers certain advantages.

The Birth of a Nation

seeks to present a panoramic vision of a period in American history (seen through peculiarly racist spectacles). Omniscient narration is thus essential to creating the sense of many destinies intertwined with the fate of the country. Had Griffith restricted narration the way

The Big Sleep

does, we would have learned story information solely through one character—say, Ben Cameron. We could not witness the prologue scene, or the scenes in Lincoln’s office, or most of the battle episodes, or the scene of Lincoln’s assassination, since Ben is present at none of these events. The plot would now concentrate on one man’s experience of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Similarly,

The Big Sleep

derives functional advantages from its restricted narration. By limiting us to Marlowe’s range of knowledge, the film can create curiosity and surprise. Restricted narration is important to mystery films, since the films engage our interest by hiding certain important causes. Confining the plot to an investigator’s range of knowledge plausibly motivates concealing other story information.

The Big Sleep

could have been less restricted by, say, alternating scenes of Marlowe’s investigation with scenes that show the gambling boss, Eddie Mars, planning his crimes, but this would have given away some of the mystery. In each of the two films, the narration’s range of knowledge functions to elicit particular reactions from the viewer.

“In the first section

[of Reservoir Dogs],

up until Mr. Orange shoots Mr. Blonde, the characters have far more information about what’s going on than you have—and they have conflicting information. Then the Mr. Orange sequence happens and that’s a great leveller. You start getting caught up with exactly what’s going on, and in the third part, when you go back into the warehouse for the climax you are totally ahead of everybody—you know far more than any one of the characters.”— Quentin Tarantino, director

Unrestricted and restricted narration aren’t watertight categories but rather are two ends of a continuum. Range is a matter of degree. A film may present a broader range of knowledge than does

The Big Sleep

and still not attain the omniscience of

The Birth of a Nation.

In

North by Northwest,

for instance, the early scenes confine us pretty much to what Roger Thornhill sees and knows. After he flees from the United Nations building, however, the plot moves to Washington, where the members of the U.S. Intelligence Agency discuss the situation. Here the viewer learns something that Roger Thornhill will not learn for some time: the man he seeks, George Kaplan, does not exist. Thereafter, we have a greater range of knowledge than Roger does. In at least one important respect, we also know more than the Agency’s staff: we know exactly how the mix-up took place. But we still do not know many other things that the narration could have divulged in the scene in Washington. For instance, the Agency’s staff do not identify the real agent they have working under Van Damm’s nose. In this way, any film may oscillate between restricted and unrestricted presentation of story information.

Across a whole film, narration is never completely unrestricted. There is always something we are not told, even if it is only how the story will end. Usually, we think of a typical unrestricted narration as operating in the way that it does in

The Birth of a Nation:

the plot shifts constantly from character to character to change our source of information.

Similarly, a completely restricted narration is not common. Even if the plot is built around a single character, the narration usually includes a few scenes that the character is not present to witness. Though

Tootsie

’s narration remains almost entirely attached to actor Michael Dorsey, a few shots show his acquaintances shopping or watching him on television.

The plot’s range of story information creates a

hierarchy of knowledge.

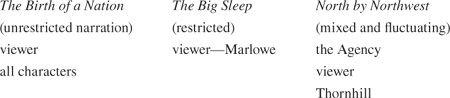

At any given moment, we can ask if the viewer knows more than, less than, or as much as the characters do. For instance, here’s how hierarchies would look for the three films we have been discussing. The higher someone is on the scale, the greater his or her range of knowledge:

An easy way to analyze the range of narration is to ask,

Who knows what when?

The spectator must be included among the “whos,” not only because we may get more knowledge than any one character but also because we may get knowledge that

no

character possesses. We shall see this happen at the end of

Citizen Kane.

Our examples suggest the powerful effects that narration can achieve by manipulating the range of story information. Restricted narration tends to create greater curiosity and surprise for the viewer. For instance, if a character is exploring a sinister house, and we see and hear no more than the character does, a sudden revelation of a hand thrusting out from a doorway will startle us.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Cloverfield

uses an unusually restricted narration, confining itself to film shot by the main characters. See our analysis, “A behemoth from the Dead Zone,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=1844

.

In contrast, as Hitchcock pointed out, a degree of unrestricted narration helps build suspense. He explained it this way to François Truffaut:

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but prior to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions this innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb beneath you and it’s about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense. The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. (François Truffaut,

Hitchcock

[New York: Simon & Schuster, 1967],

p. 52

)

Hitchcock put his theory into practice. In

Psycho,

Lila Crane explores the Bates mansion in much the same way as our hypothetical character is doing above. There are isolated moments of surprise as she discovers odd information about Norman and his mother. But the overall effect of the sequence is built on suspense because we know, as Lila does not, that Mrs. Bates is in the house. (Actually, as in

North by Northwest,

our knowledge isn’t completely accurate, but during Lila’s investigation, we believe it to be.) As in Hitchcock’s anecdote, our superior range of knowledge creates suspense because we can anticipate events that the character cannot.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

We present a more detailed discussion of the distinction between perceptual and mental subjectivity in narration in “Categorical coherence: A closer look at character subjectivity.”

A film’s narration manipulates not only the range of knowledge but also the depth of our knowledge. Here we are referring to how deeply the plot plunges into a character’s psychological states. Just as there is a spectrum between restricted and unrestricted narration, there is a continuum between objectivity and subjectivity.

A plot might confine us wholly to information about what characters say and do: their external behavior. Here the narration is relatively

objective.

Or a film’s plot may give us access to what characters see and hear. We might see shots taken from a character’s optical standpoint, the

point-of-view shot

. For instance, in

North by Northwest,

point-of-view editing is used as we see Roger Thornhill crawl up to Van Damm’s window

(

3.15

–

3.17

).

Or we might hear sounds as the character would hear them, what sound recordists call

sound perspective.

Visual or auditory point of view offers a degree of subjectivity, one we might call

perceptual subjectivity.

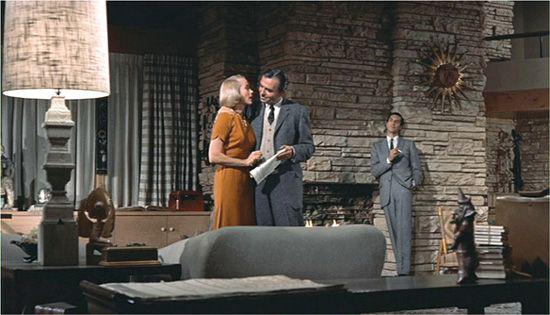

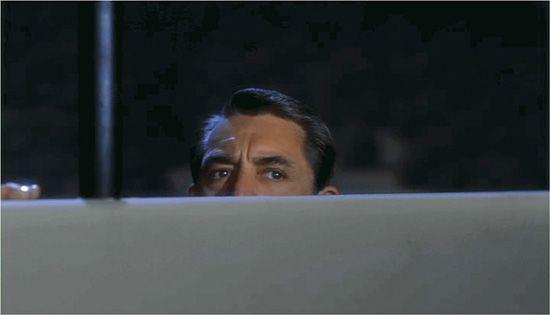

3.15 In

North by Northwest,

Roger Thornhill looks in Van Damm’s window (objective narration).

3.16 A shot from Roger’s point of view follows (perceptual subjectivity).

3.17 This is followed by another shot of Roger looking (objectivity again).

There is the possibility of still greater depth if the plot plunges into the character’s mind. We can call this

mental subjectivity.

We might hear an internal voice reporting the character’s thoughts, or we might see the character’s inner images, representing memory, fantasy, dreams, or hallucinations. In

Slumdog Millionaire,

the hero is a contestant on a quiz show, but his concentration is often interrupted by brief shots of his memories, particularly one image of the woman he loves

(

3.18

–

3.19

).

Here Jamal’s memory motivates flashbacks to earlier story events.