B0041VYHGW EBOK (32 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

It’s not accidental that all of the traits that Indiana Jones displays in the opening scene are relevant to later scenes in

Raiders.

In general, a character is given traits that will play causal roles in the overall story action. The second scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s

The Man Who Knew Too Much

(1934) shows that the heroine, Jill, is an excellent shot with a rifle. For much of the film, this trait seems irrelevant to the action, but in the last scene, Jill is able to shoot one of the villains when a police marksman cannot do it. This skill with a rifle is a trait that helps make up a character named Jill, and it serves a particular narrative function.

Not all causes and effects in narratives originate with characters. In the socalled disaster movies, an earthquake or tidal wave may precipitate a series of actions on the parts of the characters. The same principle holds when the shark in

Jaws

terrorizes a community. Still, once these natural occurrences set the situation up, human desires and goals usually enter the action to develop the narrative. A man escaping from a flood may be placed in the situation of having to decide whether to rescue his worst enemy. In

Jaws,

the townspeople pursue a variety of strategies to deal with the shark, propelling the plot as they do so.

In general, the spectator actively seeks to connect events by means of cause and effect. Given an incident, we tend to imagine what might have caused it or what it might in turn cause. That is, we look for causal motivation. We have mentioned an instance of this in

Chapter 2

: In the scene from

My Man Godfrey,

a scavenger hunt serves as a cause that justifies the presence of a beggar at a society ball (see

p. 68

).

Causal motivation often involves the planting of information in advance of a scene, as we saw in the kitchen scene of

The Shining

(

2.7

,

2.8

). In

L.A. Confidential,

the idealistic detective Exley confides in his cynical colleague Vincennes that the murder of his father had driven him to enter law enforcement. He had privately named the unknown killer “Rollo Tomasi,” a name that he has turned into an emblem of all unpunished evil. This conversation initially seems like a simple bit of psychological insight. Yet later, when the corrupt police chief Smith shoots Vincennes, the latter mutters “Rollo Tomasi” with his last breath. When the puzzled Smith asks Exley who Rollo Tomasi is, Exley’s earlier conversation with Vincennes motivates his shocked realization that the dead Vincennes has given him a clue to his killer. Near the end, when Exley is about to shoot Smith, he says that the chief is Rollo Tomasi. Thus an apparently minor detail returns as a major causal and thematic motif. And perhaps the unusual name, Rollo Tomasi, functions to help the audience remember this motif.

Most of what we have said about causality pertains to the plot’s direct presentation of causes and effects. In

The Man Who Knew Too Much,

Jill is shown to be a good shot, and because of this, she can save her daughter. But the plot can also lead us to

infer

causes and effects, and thus build up a total story. The detective film furnishes the best example of how we actively construct the story.

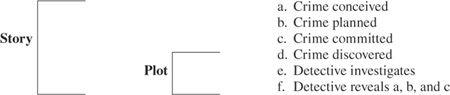

A murder has been committed. That is, we know an effect but not the causes—the killer, the motive, and perhaps also the method. The mystery tale thus depends strongly on curiosity—on our desire to know events that have occurred before the events that the plot presents to us. It’s the detective’s job to disclose, at the end, the missing causes—to name the killer, explain the motive, and reveal the method. That is, in the detective film, the climax of the plot (the action we see) is a revelation of prior incidents in the story (events we did not see). We can diagram this:

Although this pattern is most common in detective narratives, any film’s plot can withhold causes and thus arouse our curiosity. Horror and science fiction films often leave us temporarily in the dark about what forces lurk behind certain events. Not until three-quarters of the way through

Alien

do we learn that the science officer Ash is a robot conspiring to protect the alien. In

Caché,

a married couple receive an anonymous videotape recording their daily lives. The film’s plot shows them trying to discover who made it and why it was made. In general, whenever any film creates a mystery, it suppresses certain story causes and presents only effects in the plot.

The plot may also present causes but withhold story

effects,

prompting suspense and uncertainty in the viewer. After Hannibal Lecter’s attack on his guards in the Tennessee prison in

The Silence of the Lambs,

the police search of the building raises the possibility that a body lying on top of an elevator is the wounded Lecter. After an extended suspense scene, we learn that he has switched clothes with a dead guard and escaped.

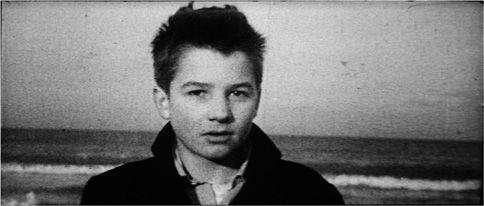

A plot’s withholding of effects can provide a vivid ending. A famous example occurs in the final moments of François Truffaut’s

The 400 Blows.

The boy Antoine Doinel, having escaped from a reformatory, runs along the seashore. The camera zooms in on his face, and the frame freezes

(

3.8

).

The plot does not reveal if he is captured and brought back, leaving us to speculate on what might happen in Antoine’s future.

3.8 The final image of

The 400 Blows

leaves Antoine’s future uncertain.

Causes and their effects are basic to narrative, but they take place in time. Here again our story–plot distinction helps clarify how time shapes our understanding of narrative action.

As we watch a film, we construct story time on the basis of what the plot presents. For example, the plot may present events out of chronological order. In

Citizen Kane,

we see a man’s death before we see his youth, and we must build up a chronological version of his life. Even if events are shown in chronological order, most plots don’t show every detail from beginning to end. We assume that the characters spend uneventful time sleeping, traveling from place to place, eating, and the like, but the story duration containing irrelevant action has simply been skipped over. Another possibility is to have the plot present the same story event more than once, as when a character recalls a traumatic incident. In John Woo’s

The Killer,

an accident in the opening scene blinds a singer, and later we see the same event again and again as the protagonist regretfully thinks back to it.

Such options mean that in constructing the film’s story out of its plot, the viewer is engaged in trying to put events in chronological

order

and to assign them some

duration

and

frequency.

We can look at each of these temporal factors separately.

We are quite accustomed to films that present events out of story

order

. A flashback is simply a portion of a story that the plot presents out of chronological order. In

Edward Scissorhands,

we first see the Winona Ryder character as an old woman telling her granddaughter a bedtime story. Most of the film then shows events that occurred when she was a high school girl. Such reordering doesn’t confuse us because we mentally rearrange the events into the order in which they would logically have to occur: childhood comes before adulthood. From the plot order, we infer the story order. If story events can be thought of as ABCD, then the plot that uses a flashback presents something like BACD. Similarly, a flash-forward—that is, moving from present to future then back to the present—would also be an instance of how plot can shuffle story order. A flash-forward could be represented as ABDC.

One common pattern for reordering story events is an alternation of past and present in the plot. In the first half of Terence Davies’

Distant Voices, Still Lives,

we see scenes set in the present during a young woman’s wedding day. These alternate with flashbacks to a time when her family lived under the sway of an abusive, mentally disturbed father. Interestingly, the flashback scenes are arranged out of chronological story order: childhood episodes alternate with scenes of adolescence, further cueing the spectator to assemble a linear story.

Sometimes a fairly simple reordering of scenes can create complicated effects. The plot of Quentin Tarantino’s

Pulp Fiction

begins with a couple deciding to rob the diner in which they’re eating breakfast. This scene takes place fairly late in the story, but the viewer doesn’t learn this until near the end of the film, when the robbery interrupts a dialogue involving other, more central, characters eating breakfast in the same diner. Just by pulling a scene out of order and placing it at the start, Tarantino creates a surprise. At another point in

Pulp Fiction,

a hired killer is shot to death. But he reappears alive in subsequent scenes, which show him and his partner trying to dispose of a dead body. Tarantino has shifted a block of scenes from the middle of the story (before the man was killed) to the end of the plot. By coming at the film’s conclusion, these portions receive an emphasis they wouldn’t have if they had remained in their chronological story order.

The plot of

North by Northwest

presents four crowded days and nights in the life of Roger Thornhill. But the story stretches back far before that, since information about the past is revealed in the course of the plot. The story events include Roger’s past marriages, the U.S. Intelligence Agency’s plot to create a false agent named George Kaplan, and the villain Van Damm’s series of smuggling activities.

In general, a film’s plot selects certain stretches of story

duration

. This could involve concentrating on a short, relatively cohesive time span, as

North by Northwest

does. Or it could involve highlighting significant stretches of time from a period of many years, as

Citizen Kane

does when it shows us the protagonist in his youth, skips over some time to show him as a young man, skips over more time to show him middle-aged, and so forth. The sum of all these slices of

story

duration yields an overall

plot

duration.

But we need one more distinction. Watching a movie takes time—20 minutes or two hours or eight hours (as in Hans Jürgen Syberberg’s

Our Hitler: A Film from Germany

). There is thus a third duration involved in a narrative film, which we can call

screen

duration. The relationships among story duration, plot duration, and screen duration are complex (see

“Where to Go from Here”

for further discussion), but for our purposes, we can say this: the filmmaker can manipulate screen duration independently of the overall story duration and plot duration. For example,

North by Northwest

has an overall story duration of several years (including all relevant prior events), an overall plot duration of four days and nights, and a screen duration of about 136 minutes.

Just as plot duration selects from story duration, so screen duration selects from overall plot duration. In

North by Northwest,

only portions of the film’s four days and nights are shown to us. An interesting counterexample is

Twelve Angry Men,

the story of a jury deliberating a murder case. The 95 minutes of the movie approximate the same stretch of time in its characters’ lives.

At a more specific level, the plot can use screen duration to override story time. For example, screen duration can

expand

story duration. A famous instance is that of the raising of the bridges in Sergei Eisenstein’s

October.

Here an event that takes only a few moments in the story is stretched out to several minutes of screen time by means of the technique of film editing. As a result, this action gains a tremendous emphasis. The plot can also use screen duration to compress story time, as when a process taking hours or days is condensed into a rapid series of shots. These examples suggest that film techniques play a central role in creating screen duration. We shall consider this in more detail in

Chapters 5

and

6

.