B0041VYHGW EBOK (20 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

1.51 … thus losing the sense of actors simultaneously reacting to each other.

1.52 As Rose, the heroine of

Titanic,

feels the exhilaration of “flying” on the ship’s prow, the strongly horizontal composition emphasizes her outstretched arms as wings against a wide horizon.

1.53 In the video version, nearly all sense of the horizontal composition has disappeared.

1.54

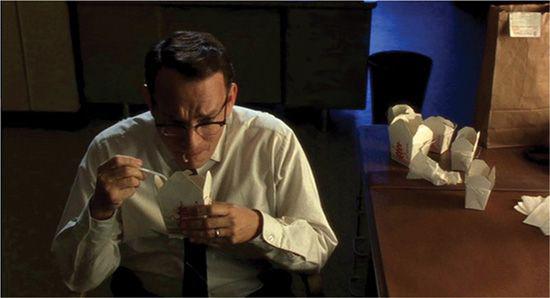

Catch Me If You Can:

As with many modern wide-screen films, the essential information on screen left would fit within a traditional television frame. Still, cropping this image would lose a secondary piece of information—the pile of take-out food cartons that implies that Agent Hanratty has been at his desk for days.

“Not until seeing

[North by Northwest]

again on the big screen did I realize conclusively what a gigantic difference screen size does make…. This may be yet another reason why younger people have a hard time with older pictures: they’ve only seen them on the tube, and that reduces films’ mystery and mythic impact.”— Peter Bogdanovich, director,

The Last Picture Show

and

Mask

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

We explore another peril of watching films on video—logos superimposed on films—in “Bugs: the secret history.”

“What about a mobile version of every film? Maybe in the future there will be four versions—film, TV, DVD, and mobile. No one knows yet.”

— Arvind Ethan David, managing director of multimedia company Slingshot

Today most cable and DVD versions of films are

letterboxed.

Dark bands at the top and bottom of the screen approximate the film’s theatrical proportions. The great majority of filmmakers approve of this, but Stanley Kubrick preferred that video versions of some of his films be shown “full frame.” This is why we’ve reproduced the shots from

The Shining

(

2.7

,

2.8

) full-frame, even though nobody who watched the movie in a theater saw so much headroom. Almost no commercial theaters can show films full-frame today, but Jean-Luc Godard usually composes his shots for that format; you couldn’t letterbox

1.55

without undermining the composition. In these instances, distribution and theatrical exhibition initially constrained the filmmakers’ choices, but video versions expanded them.

1.55 A very dense shot from the climax of Godard’s

Detective.

Although Godard’s films are sometimes cropped for theater screenings and DVD versions, the compositions show to best advantage in the older, squarer format.

The introduction of widescreen TV sets has created a new problem for film images. The screens of traditional sets had a 4:3 ratio, partly because a lot of programming either consisted of old films or was shot on film. Widescreen TVs may be fine for recent films, but older material can suffer—including TV shows originally made to fit standard sets. A widescreen TV image has an aspect ratio of 16:9. If we multiply a 4:3 ratio by three, we get 12:9. So the widescreen image is a third wider than the standard one. Some sets have controls to adjust the ratio and allow black bands on the sides to provide “windowboxing,” the vertical equivalent of letterboxing. But if there’s no windowboxing, the picture is stretched horizontally, so that people and objects look squashed

(

1.56

).

Many viewers do not know how to change the ratio, and some video monitors make it difficult to correct the problem.

1.56

Angel Face

as rendered on an incorrectly set widescreen television monitor.

Even product placement offers some artistic opportunities. We’re usually distracted when a Toyota truck or a box of Frosted Flakes pops up on the screen, but

Back to the Future

cleverly integrates brands into its story. Marty McFly is catapulted from 1985 to 1955. Trapped in a period when diet soda didn’t exist, he asks for a Pepsi Free at a soda fountain, but the counterman says that it’s not free—he’ll have to pay for it. Later, buying a bottle of Pepsi from a vending machine, Marty tries frantically to twist off the cap, but his father-to-be George McFly casually pops it off at the machine’s built-in opener. Pepsi soft drinks weave through the movie, reasserting Marty’s comic inability to adjust to his parents’ era—and perhaps stirring some nostalgia in viewers who remember how bits of everyday life have changed since their youth.

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

Jean-Luc Godard’s films present special challenges to the projectionist and DVD producer, as we show in “Godard comes in many shapes and sizes.”

The art of film depends on technology, from the earliest experiments in apparent motion to the most recent computer programs. It also depends on people who use that technology, who come together to make films, distribute them, and show them. As long as a film is aimed at a public, however small, it enters into the social dynamic of production, distribution, and exhibition. Out of technology and work processes, filmmakers create an experience for audiences. Along the way, they inevitably make choices about form and style. What options are available to them? How might filmmakers organize the film as a whole? How might they draw on the techniques of the medium? The next two parts of this book survey the possibilities.

WHERE TO GO FROM HERE

Collateral

Our case study of

Collateral

’s production derives in part from the making-of supplement, “City of Night: The Making of

Collateral.

” This 39-minute documentary covers the decisions about filming on HD-video, about lighting the interior of the taxi, and about the three-movement musical track that accompanies the climax. This and some short films on the actors rehearsing and on the special effects of the final sequence appear in the two-disc DVD set (Dream Works Home Entertainment #91734; this DVD was issued only in a letterboxed version).

Jay Holben’s

American Cinematographer

article “Hell on Wheels” (

pp. 40

–51 in the August 2004 issue) deals in greater detail with the cameras used in the production and with the lighting. David Goldsmith describes the original version of the script, set in New York City, in “

Collateral:

Stuart Beattie’s Character-Driven Thriller,”

Creative Screenwriting,

11, 4 (2004): 50–53. Two online articles that deal with the film’s filmmaking choices and style are Bryant Frazer’s “How DP Dion Beebe Adapted to HD for Michael Mann’s

Collateral,

” on the website of the International Cinematographers Guild (n.d.),

www.cameraguild.com/interviews/chat_beebe/beebe_collateral.html

, and Daniel Restuccio’s “Seeing in the Dark for

Collateral

: Director Michael Mann Re-invents Digital Filmmaking” (August 2004),

findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HNN/is_8_19/ai_ n6171215/pg_1

.

For about 80 years, writers on film have maintained that the reason we see movement in movies is due to “persistence of vision.” Today, no researcher into perception is likely to accept this explanation. Several optical processes are involved, but as we indicate on p. 000, the two most prominent are flicker fusion and apparent motion. More specifically, the stimuli in a film instantiate “short-range” apparent motion, in which small-scale changes in the display trigger activity in different parts of the visual cortex. Filmic motion takes place in our brain, not on our retina. For an explanation of these ideas, and a thorough critique of the traditional explanation, see Joseph and Barbara Anderson, “The Myth of Persistence of Vision Revisited,”

Journal of Film and Video,

45, 1 (Spring 1993): 3–12. It is available online at

www.uca.edu/org/ccsmi/ccsmi/classicwork/myth%20revisited.htm

.

André Bazin suggests that humankind dreamed of cinema long before it actually appeared: “The concept men had of it existed so to speak fully armed in their minds, as if in some platonic heaven” (

What Is Cinema?

vol. 1 [Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967],

p. 17

). Still, whatever its antecedents in ancient Greece and the Renaissance, the cinema became technically feasible only in the 19th century.

Motion pictures depended on many discoveries in various scientific and industrial fields: optics and lens making, the control of light (especially by means of arc lamps), chemistry (involving particularly the production of cellulose), steel production, precision machining, and other areas. The cinema machine is closely related to other machines of the period. For example, engineers in the 19th century designed machines that could intermittently unwind, advance, perforate, advance again, and wind up a strip of material at a constant rate. The drive apparatus on cameras and projectors is a late development of a technology that had already made feasible the sewing machine, the telegraph tape, and the machine gun. The 19-century origins of film, based on mechanical and chemical processes, are particularly evident today, since we’ve become accustomed to electronic and digital media.

On the history of film technology, see Barry Salt’s

Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis

(London: Starword, 1983); and Leo Enticknap,

Moving Image Technology: From Zoetrope to Digital

(London: Wallflower, 2005). Douglas Gomery has pioneered the economic history of film technology: For a survey, see Robert C. Allen and Douglas Gomery,

Film History: Theory and Practice

(New York: Knopf, 1985). The most comprehensive reference book on the subject is Ira Konigsberg,

The Complete Film Dictionary

(New York: Penguin, 1997). An entertaining appreciation of film technology is Nicholson Baker’s “The Projector,” in his

The Size of Thoughts

(New York: Vintage, 1994),

pp. 36

–50. Brian McKernan provides an overview of the introduction and development of digital technology in

Digital Cinema: The Revolution in Cinematography, Postproduction, and Distribution

(New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005).

For comprehensive surveys of the major “content providers” today, see Benjamin M. Compaine and Douglas Gomery,

Who Owns the Media? Competition and Concentration in the Mass Media Industry

(Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2000); Barry R. Litman,

The Motion Picture Mega-Industry

(Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 1998); and Edward S. Herman and Robert W. McChesney,

The Global Media: The New Missionaries of Global Capitalism

(London: Cassell, 1997).

Edward J. Epstein offers an excellent overview of the major distributors’ activities in

The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood

(New York: Random House, 2005). Douglas Gomery’s

The Hollywood Studio System: A History

(London: British Film Institute, 2005) traces the history of the distributors, showing their roots in vertically integrated studios, which controlled production and exhibition as well.

On moviegoing, see Bruce A. Austin,

Immediate Seating: A Look at Movie Audiences

(Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1988); Gregory A. Waller, ed.,

Moviegoing in America: A Sourcebook in the History of Film Exhibition

(Oxford: Blackwell, 2002); and Richard Maltby, Melvyn Stokes, and Robert C. Allen, eds.,

Going to the Movies: Hollywood and the Social Experience of Cinema

(Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2007). Douglas Gomery’s

Shared Pleasures: A History of Moviegoing in America

(Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992) offers a history of U.S. exhibition.

A very good survey of production is Stephen Asch and Edward Pincus’s

The Filmmaker’s Handbook

(New York: Plume, 1999). For the producer, see Paul N. Lazarus III,

The Film Producer

(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991) and Lynda Obst’s acerbic memoir,

Hello, He Lied

(New York: Broadway, 1996). Art Linson, producer of

The Untouchables

and

Fight Club,

has written two entertaining books about his role:

A Pound of Flesh: Perilous Tales of How to Produce Movies in Hollywood

(New York: Grove Press, 1993) and

What Just Happened? Bitter Hollywood Tales from the Front Line

(New York: Bloomsbury, 2002). The details of organizing preparation and shooting are explained in Alain Silver and Elizabeth Ward’s

The Film Director’s Team: A Practical Guide for Production Managers, Assistant Directors, and All Filmmakers

(Los Angeles: Silman James, 1992). For a survey of directing, see Tom Kingdon,

Total Directing: Integrating Camera and Performance in Film and Television

(Beverly Hills, CA: Silman-James, 2004). Many “making-of” books include examples of storyboards; see also Steven D. Katz,

Film Directing Shot by Shot

(Studio City, CA: Wiese, 1991). On setting and production design, see Ward Preston,

What an Art Director Does

(Los Angeles: Silman-James, 1994). Norman Hollyn’s

The Film Editing Room Handbook

(Los Angeles: Lone Eagle, 1999) offers a detailed account of image and sound editing procedures. Computer-based methods are discussed in Gael Chandler,

Cut by Cut: Editing Your Film or Video

(Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese, 2004). A wide range of job titles, from Assistant Director to Mouth/Beak Replacement Coordinator, is explained by the workers themselves in Barbara Baker,

Let the Credits Roll: Interviews with Film Crew

(Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2003).

Several books explain how independent films are financed, produced, and sold. The most wide-ranging are David Rosen and Peter Hamilton,

Off-Hollywood: The Making and Marketing of Independent Films

(New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990), and Gregory Goodell,

Independent Feature Film Production: A Complete Guide from Concept Through Distribution,

2d ed. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998). Billy Frolick’s

What I Really Want to Do Is Direct

(New York: Plume, 1997) follows seven film-school graduates trying to make low-budget features. Christine Vachon, producer of

Boys Don’t Cry

and

Far from Heaven,

shares her insights in

Shooting to Kill

(New York: Avon, 1998). See also Mark Polish, Michael Polish, and Jonathan Sheldon,

The Declaration of Independent Filmmaking: An Insider’s Guide to Making Movies Outside of Hollywood

(Orlando, FL: Harcourt, 2005).

In

How I Made a Hundred Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime

(New York: Random House, 1990), Roger Corman reviews his career in exploitation cinema. A sample passage: “In the first half of 1957 I capitalized on the sensational headlines following the Russians’ launch of their Sputnik satellite…. I shot

War of the Satellites

in a little under ten days. No one even knew what the satellite was supposed to look like. It was whatever I said it should look like” (

pp. 44

–45). Corman also supplies the introduction to Lloyd Kaufman’s

All I Needed to Know about Filmmaking I Learned from the Toxic Avenger: The Shocking True Story of Troma Studios

(New York: Berkeley, 1998), which details the making of such Troma classics as

The Class of Nuke ’Em High

and

Chopper Chicks in Zombietown.

See as well the interviews collected in Philip Gaines and David J. Rhodes,

Micro-Budget Hollywood: Budgeting

(

and Making

)

Feature Films for $50,000 to $500,000

(Los Angeles: Silman-James, 1995).

John Pierson, a producer, distributor, and festival scout, traces how

Clerks; She’s Gotta Have It; sex, lies, and videotape;

and other low-budget films found success in

Spike, Mike, Slackers, and Dykes

(New York: Hyperion Press, 1995). Emanuel Levy’s

Cinema of Outsiders: The Rise of American Independent Film

(New York: New York University Press, 1999) provides a historical survey. The early history of an important distributor of independent films, Miramax, is examined in Alissa Perren, “sex, lies and marketing: Miramax and the Development of the Quality Indie Blockbuster,”

Film Quarterly

55, 2 (Winter 2001–2002): 30–39.

We can learn a great deal about production from careful case studies. See Rudy Behlmer,

America’s Favorite Movies: Behind the Scenes

(New York: Ungar, 1982); Aljean Harmetz,

The Making of “The Wizard of Oz”

(New York: Limelight, 1984); John Sayles,

Thinking in Pictures: The Making of the Movie “Matewan”

(Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987); Ronald Haver, “

A Star Is Born”: The Making of the 1954 Movie and Its 1985 Restoration

(New York: Knopf, 1988); Stephen Rebello,

Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of “Psycho”

(New York: Dembuer, 1990); Paul M. Sammon,

Future Noir: The Making of “Blade Runner”

(New York: HarperPrism, 1996); and Dan Auiler, “

Vertigo”: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic

(New York: St. Martin’s, 1998). John Gregory Dunne’s

Monster: Living off the Big Screen

(New York: Vintage, 1997) is a memoir of eight years spent rewriting the script that became

Up Close and Personal.

Many of Spike Lee’s productions have been documented with published journals and production notes; see, for example,

“Do The Right Thing”: A Spike Lee Joint

(New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989). For the independent scene, Vachon’s

Shooting to Kill,

mentioned above, documents the making of Todd Haynes’s

Velvet Goldmine.

Collections of interviews with filmmakers have become common in recent decades. We will mention interviews with designers, cinematographers, editors, sound technicians, and others in the chapters on individual film techniques. The director, however, supervises the entire process of filmmaking, so we list here some of the best interview books: Peter Bogdanovich,

Who the Devil Made It

(New York: Knopf, 1997); Mike Goodrich,

Directing

(Crans Prés-Céligny, 2002); Jeremy Kagan,

Directors Close Up

(Boston: Focal Press, 2000); Andrew Sarris, ed.,

Interviews with Film Directors

(Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967); and Gerald Duchovnay,

Film Voices: Interviews from Post Script

(Albany: SUNY Press, 2004). Paul Cronin has collected the writings of Alexander Mackendrick in

On Filmmaking

(London: Faber & Faber, 2004). Mackendrick was a fine director and a superb teacher, and the book offers incisive advice on all phases of production, from screenwriting (“Use coincidence to get characters into trouble, not out of trouble”) to editing (“The geography of the scene must be immediately apparent to the audience”). See also Laurent Tirard,

Moviemakers’ Master Class: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors

(New York: Faber & Faber, 2002). Some important directors have written books on their craft, including Edward Dmytryk,

On Screen Directing

(Boston: Focal Press, 1984); David Mamet,

On Directing Film

(New York: Penguin, 1992); Sidney Lumet,

Making Movies

(New York, Knopf, 1995); and Mike Figgis,

Digital Filmmaking

(New York: Faber & Faber, 2007).