B0041VYHGW EBOK (19 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

1.43 In

Magnolia,

the figure 82 appears as coils in the rooftop hose.

As the Internet becomes a more common platform for distribution, we should expect variations in narrative form. Short-form storytelling is already at home online, in cartoons and comedy. Events like the festivals run by the 48 Hour Film Project also encourage the making of short films, especially given the assumption that most of the films will later be posted on the Internet. We’re likely to find movies designed specifically for mobile phones; television series like

24

are already creating “mobisodes” branching off the broadcast story line. The web is the logical place for interactive films that use hyperlinks to amplify or detour a line of action.

Marketing and merchandising can extend a theatrical film’s story in intriguing ways. The

Star Wars

novels and video games give the characters more adventures and expand spectators’ engagement with the movies. The

Memento

website hinted at ways to interpret the film. The

Matrix

video games supplied key information for the films’ plots, while the second movie in the trilogy sneaked in hints for winning the games. As a story world shifts from platform to platform, a multimedia saga is created, and viewers’ experiences will shift accordingly.

Matrix

viewers who’ve never played the games understand the story somewhat differently from those who have.

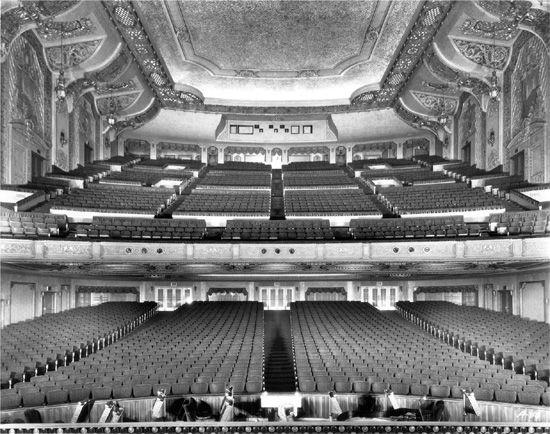

Style can be affected by distribution and exhibition, as is evident in image size. From the 1920s through the 1950s, films were designed to be shown in large venues

(

1.44

).

A typical urban movie house seated 1500 viewers and boasted a screen 50 feet wide. This scale gave the image great presence, and it allowed details to be seen easily. Directors could stage dialogue scenes showing several characters in the frame, all of whom would be prominent

(

1.45

).

In a theater of that time, a tight close-up would have had a powerful impact.

1.44 The interior of the Paramount Theater in Portland, Oregon, built in 1928. Capacity was 3000 seats, at a time when the city population was about 300,000. Note the elaborate decoration on the walls and ceilings, typical of the “picture palaces” of the era.

1.45 On the large screen of a picture palace, all the figures and faces in this shot from

The Thin Man

(1934) would have been quite visible.

“The Matrix

is entertainment for the age of media convergence, integrating multiple texts to create a narrative so large that it cannot be contained within a single medium.

”— Henry Jenkins, media analyst

CONNECT TO THE BLOG

For some pictures of a spectacularly restored movie palace, see “A tale of 2—make that 1 and 1/3 screens,” at

www.davidbordwell.net/blog/?p=3941

.

When television became popular in the 1950s, its image was rather unclear and very small, in some cases only 10 inches diagonally. Early TV shows tended to rely on close shots

(

1.46

),

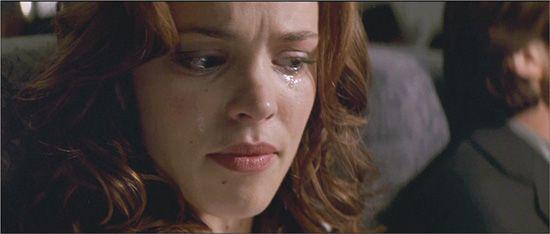

which could be read easily on the small monitor. In the 1960s and 1970s, movie attendance dropped and theaters became smaller. As screens shrank, filmmakers began to rely more on close-ups in the TV manner. This tendency has continued until today. Although modern multiplex screens can be fairly large, audiences have become accustomed to scenes that consist chiefly of big faces

(

1.47

).

Now that most films are viewed on video, and many will be watched on handheld devices, it seems likely that commercial films will continue to treat conversation scenes in tight close-ups. In this respect, technology and exhibition circumstances have created stylistic constraints. Yet some contemporary filmmakers have stuck to the older technique

(

1.48

),

in effect demanding that audiences view their films on a large theater screen.

1.46

Dragnet

(1953): Early television relied heavily on close-ups because of the small screen size.

1.47

Red Eye:

Extreme close-ups of actors’ faces are common in modern cinema, due partly to the fact that most viewing takes place on video formats.

1.48 In

Flowers of Shanghai,

director Hou Hsiao-hsien builds every scene out of full shots of several characters. The result loses information on a small display and is best seen on a theater screen.

There’s also the matter of image proportions, and here again, television exhibition exercised some influence. Since the mid-1950s, virtually all theaters have shown films on screens that were wider than the traditional TV monitor. For decades, when movies were shown on television, they were cropped, with certain areas simply left out

(

1.49

–

1.51

).

In response, some filmmakers composed their shots to include a “safe area,” placing the key action in a spot that could fit snugly on the television screen. This created subtle differences in a shot’s visual effects

(

1.52

,

1.53

).

Relying on the safe area often encouraged filmmakers to employ more

singles,

shots showing only one player. In a wide-screen frame, a single can compensate for the cropping that TV would demand

(

1.54

).

1.49 In Otto Preminger’s

Advise and Consent,

a single shot in the original …

1.50 … becomes a pair of shots in the television version …