B0041VYHGW EBOK (177 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

The reenactments present different versions of the crime in accord with different witnesses’ recollections. By presenting contradictory versions of what happened that night, Morris may seem to be suggesting that everyone involved saw things from his or her own perspective, and so there is no final fact of the matter. But the overall progression of the film leads us to a likely conclusion: that David Harris, on his own, killed Wood. Rather than suggesting that truth is relative, the incompatible reconstructions dramatize the conflicting testimony. Like jurors or courtroom spectators, we have to decide on the most plausible version, and the plot develops the reenactments in a strongly suggestive pattern.

In the segments devoted to the police investigation, the restagings emphasize matters of procedure. Did Officer Turko identify the car correctly? No, the police detectives eventually decide; but both before and after they arrive at this conclusion, Morris shows us two different cars, making the options visually concrete. Another question is just as important: Did Turko back up Officer Wood according to procedure, or did she remain in the car? Morris dramatizes both possibilities, but he leads us to infer that she probably was inside the car drinking her milkshake, since in the crime scene sketch, spilled chocolate liquid was found near the car. It is a matter of probabilities, and we can never be certain; but on the evidence we are given, we infer that she probably did not back up Wood.

The reenactments of Officer Wood’s murder in the investigation section have concentrated on police procedure, but during the trial section, the reenactments suggest different versions of what was happening in the killer’s car. Was David Harris ducking down in the front seat? Was Adams’s bushy silhouette confused with a fur-lined coat collar? When the surprise witnesses are introduced, Morris shows reenactments that present their cars passing the murder scene. Again, the reconstructions present the alternatives neutrally, but some become more plausible than others, especially once the eyewitnesses are rebutted by other testimony or betrayed by their own evasive answers.

The last reenactment, presented in the section devoted to David Harris, shows how Harris could have committed the murder, and significantly, it is accompanied by his voice-over commentary virtually confessing to it. Now, after many other reenactments, this one is presented as most worthy of our belief. Morris carefully refrains from saying explicitly that Harris was the killer. But the development of the reconstructions, eliminating the most questionable versions and focusing more and more on the identity of the driver, pushes us toward accepting this as the likeliest account.

As in any narrative film, then, the manner of storytelling, the play with narration and knowledge, shapes our attitudes toward the characters. By letting Adams comment on other characters, and by arranging the reenactments so as to point eventually toward David Harris’s guilt, the film aligns us with Randall Adams, the innocent victim. Correspondingly, Morris uses other stylistic devices to make us mistrust the forces set against Adams. The film doesn’t present the Dallas law officers as brutal villains; all are soft-spoken and articulate, and Judge Metcalfe comes across as calm and patient. But the editing gives Adams’s account prominence and allows him to answer their charges, so we are inclined to appraise their words cautiously.

Most overtly critical of the authorities are two nearly comic digressions close to the sort of associational form exploited by Bruce Conner in

A Movie

(

pp. 365

–370). Judge Metcalfe recalls that he grew up with a great respect for law and order because his father was present when FBI agents shot the gangster John Dillinger

(

11.86

).

Morris cuts to a scene from a Hollywood crime movie that presents Dillinger’s death

(

11.87

).

Metcalfe also supplies background trivia about the woman who betrayed Dillinger, and when he says she was sent back to her native Romania, Morris cuts to a map of Bucharest (a moment of self-parody, since he has used maps many times in the course of the film). A parallel montage appears during the remarks of one eyewitness, who says she always imagined herself as a girl detective, as in 1950s TV shows. Morris lets her voice-over commentary run during a clip from a B-film in which a young woman helps a detective capture a crook. These sequences encourage us to see Adams’s adversaries as holding a conception of crimefighting derived from popular movies.

11.86 Judge Metcalfe recalls the death of Dillinger …

11.87 … and Morris cuts to a B-movie scene showing the outlaw’s death, as if to recall an earlier attempt at the sort of reenactments in

The Thin Blue Line.

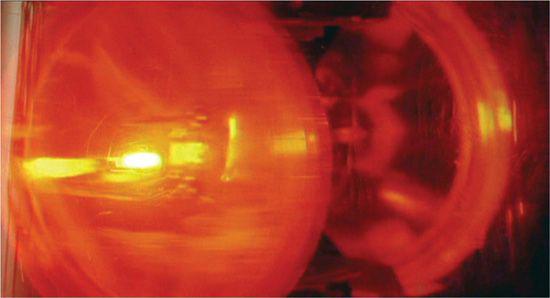

The color motifs that evoke police authority and duplicity are subtler. The first few shots of the film show skyscrapers and other structures, each with a single blinking red light

(

11.88

).

After a cut to Randall Adams beginning his tale, the screen goes dark, and we see the rotating red light of a police car, an image that will recur elsewhere in the film

(

11.89

),

before cutting to David Harris’s account of how he came to Dallas. The motif of redness links Dallas and the police as forces aligned against Adams, and it suggests an explanation for why in the opening title credit, the word

Blue

is lettered in red

(

11.90

).

The film’s title is taken from Judge Metcalfe’s reference to the prosecutor’s summation, in which he called the police the “thin blue line” between civilization and anarchy. By coloring the line red, Morris not only evokes bloodshed, but he links the police blue to the ominous blinking red lights of the opening.

11.88 Dallas cityscapes with blinking red lights.

11.89 The motif is reiterated in frequent shots of rotating police-car lights.

11.90 The film’s opening title announces the red motif.

The motif expands further into Judge Metcalfe’s account of the death of Dillinger, who was betrayed by the notorious “woman in red.” Metcalfe claims that in fact she wasn’t actually wearing red; her orange dress merely looked red in a certain light. David Harris, throughout his interviews in the film, is shown wearing an orange prison uniform, suggesting that he is another figure of betrayal and perhaps hinting at his relationship to the red of the police-car light. As a documentarist, Morris probably didn’t dictate what outfit Harris wore, but he did create other images that emphasize the color motif, and he did decide to retain Metcalfe’s (fairly irrelevant) remarks about the woman in red. Like many documentarists, Morris highlighted certain aspects of existing footage to bring out thematic implications.

The story of Randall Adams’s unjust imprisonment is presented as an intersection of several people’s lives. Instead of simplifying the case for the sake of clarity, Morris treats it as a point where many stories crisscross—the private lives of the eyewitnesses, the professional rivalries among lawyers, the Dillinger tale, TV crime dramas, scenes from the drive-in movie Adams and Harris attended. Any crime, the film suggests, will consist of this tangle of threads. Any crime will seem buried in an avalanche of details (license numbers, car makes, spilled milkshakes, TV schedules), and it will engender many alternative scenarios about what really happened.

The Thin Blue Line

builds these aspects of an investigation into its very structure and style. The narration grants each version of the shooting its time onscreen, but it finally guides us to eliminate the implausible ones. It dwells on trivial details, but finally discards certain ones as less important. And it shows that a crime’s complex mass of testimony and evidence can be sorted out. The film presents itself as both an account of what really happened on that Texas highway and a meditation on how persistent inquirers can eventually arrive at truth.

Meet Me in St. Louis

1944. MGM. Directed by Vincente Minnelli. Script by Irving Brecher and Fred F. Finklehoffe, from the book by Sally Benson. Photographed by George Folsey. Edited by Albert Akst. Music by Hugh Martin and Ralph Blane. With Judy Garland, Margaret O’Brien, Mary Astor, Lucille Bremer, Leon Ames, Tom Drake.

Just over halfway through

Meet Me in St. Louis,

Alonzo Smith announces to his assembled family that he has been transferred to a new job in New York City. “I’ve got the future to think about—the future for all of us. I’ve got to worry about where the money’s coming from,” he tells the dismayed group. These ideas of family and future, central to the form and style of the film, also create an ideological framework within which the film gains meaning and impact.