B0041VYHGW EBOK (176 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

11.80 The questioning of Randall Adams, staged so that its status as a reenactment is unmistakable.

Then the film’s plot flashes back to explain events leading up to Adams’s arrest, concentrating on the police investigation (

segments 4

–11). In the course of this, David Harris names Randall Adams as the killer (8), and Adams is arrested and interrogated (10). Eventually, the confusion about the make of the car is cleared up, though Morris hints that the police investigation was muddled (11). These sequences are interrupted by two more reenactments of Adams’s questioning and two reenactments of the death of Officer Woods.

The longest stretch of the film (segments 12–24) centers on Randall Adams’s confrontation with the courts. After his lawyers and the judge are introduced (12–13), we’re given two conflicting versions of events—Adams’s and Harris’s (14–15). Three surprise witnesses identify Adams as the shooter (16–19), although some of the testimony is undercut by a woman who claims that two witnesses bragged to her about trying to earn a reward (18). Once more, at certain moments, the crime is reenacted. The jury finds Adams guilty (20), and he’s sentenced to death (21–22). The legal maneuvers that follow put Adams in prison for life without parole (23–24).

The film has answered one question posed at the outset: now we know how Randall Adams got to prison. But what of David Harris, who is also serving time? The final large section of the film continues the story after the trial, concentrating on Harris’s criminal career. Harris is arrested for other crimes (25), and then Morris inserts a sequence (26) designed to suggest his guilt in the Woods case. The surprise eyewitnesses are shown to be unreliable and confused, and as having things to hide. Most tellingly, Harris explains, “Of course I picked out Randall Adams.” In the next sequence, a detective in Harris’s hometown of Vidor explains how Harris invaded a man’s home, violently abducted his girlfriend, and fatally shot the man (27). Harris, now revealed as a polite, easygoing sociopath, reflects on his childhood, when his brother drowned and his father seemed to become more distant (29). But whatever sympathy he might arouse is undercut by his final acknowledgment, captured by Morris on audiotape, that Randall Adams is innocent (30). A title explains that Adams is still serving his life sentence, while Harris is on death row (31).

“I wanted to make a film about how truth was difficult to know, not impossible to know.”

— Errol Morris, director

In outline, then, this is a straightforward tale of crime and injustice. The film’s explicit meaning was compelling enough to trigger a new inquiry into the case, and Adams was freed in 1989. But Morris’s film is more than a brief for the defense. It demands a great deal of the viewer; it does not spell out its message in the manner of most documentaries. We tend to side with Randall Adams and to distrust the police, prosecutors, and “eyewitnesses” aligned against him, but Morris does not explicitly favor Adams and criticize the others. The film’s form and style shape our sympathies rather subtly. At another level, the film denies the viewer many of the usual aids for determining what happened on that night in 1976. Instead, it asks us to heighten our attention, to concentrate on details, and to weigh the incompatible information we are given. Morris’s detective story asks us to reflect on the obstacles to arriving at the truth about any crime.

The film’s materials are for the most part the stuff of any true-crime report. Morris uses talking-head interviews, newspaper headlines, maps, archival photos, and other documents to present information about the crime. He also includes reenactments of key events, signaled as such. Nonetheless, other documentary conventions are missing. There is no voice-over narrator explaining the situation, and no captions identify the speakers or provide dates. The reenactments don’t carry the “Dramatization” caption seen in television documentaries. As a result, we’re forced to evaluate what we see and hear without help. This extra responsibility is intensified by a framing that is rare in most documentary interviews: several of the speakers look straight out at the camera

(

11.81

).

This somewhat unnerving direct address (which is even more prominent in other films by Morris) puts us in the position of detectives, forcing us to judge each person’s testimony. Moreover, the use of paper documents is fairly cryptic: the film doesn’t always specify their source, and the extreme close-ups often show only fragments of text. (One shot of a news article frames these partial phrases: “… ved to be a 1973 … earing Texas licens … with the letters H …”) And Philip Glass’s repetitive score is hardly conventional documentary music, especially for a true-crime story. With its mournful, unresolved harmonies and nervously oscillating figures, the music arouses tension, but it also creates an eerie distance from the action: it throbs on, unchanged whether it accompanies an empty city landscape or a violent murder.

11.81 A police detective gives his version of Adams’s interrogation.

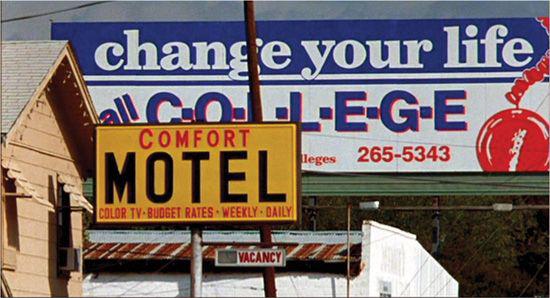

Other formal and stylistic qualities complicate the plot. For example, when an interviewee mentions a particular place, Morris tends to insert a quick shot of that locale

(

11.82

).

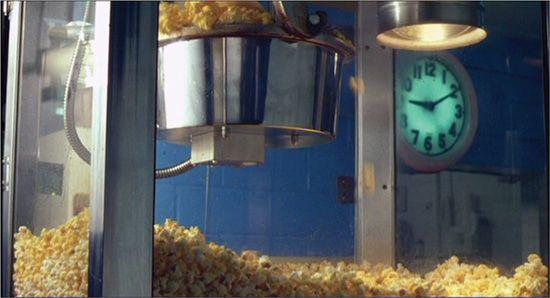

Such abrupt interruptions wouldn’t be used in a normal documentary, since they don’t really give us much extra information. It’s as if Morris wants to suggest the vast number of tiny pieces of information that an investigator must process. Similarly, during most reenactments, the participants’ faces aren’t shown. Instead, the scenes are built out of many close-ups: fingers resting on a steering wheel, a milkshake flying through the air in slow motion, the popcorn machine at a drive-in

(

11.83

).

Again, Morris stresses the apparently trivial details that can affect our sense of what really happened on the highway. Yet, carefully composed and lit in high-key, the details also become evocative motifs. Some inserts comment ironically on the situation (

11.82

). Others, such as the ever-present clocks and watches, indicate the ominous passing of time; even the slowly shattering flashlight and the milkshake dribbling onto the pavement suggest the life pumping out of the fatally wounded officer. Morris’s systematic withholding of information invites us to fill in parts of the story, and by amplifying apparently minor details he also invites us to build up implicit meanings.

11.83 The popcorn machine at the drive-in, filmed ominously in the foreground while the clock serves as the basis for David Harris’s testimony.

11.82 The motel where Adams stayed; in light of Adams’s fate, the billboard in the background becomes ironic.

Central to those meanings are our attitudes toward the people presented in the film. By and large, the plot is shaped to create sympathy for Randall Adams. He is the first person we see, and Morris immediately makes him appealing by letting him explain that he was grateful to find a good job immediately after coming to Dallas. “It’s as if I was meant to be here.” Morris presents him as a decent, hardworking man railroaded by the justice system. The interrogation of Adams is associated with filled ashtrays, making him seem nervous and vulnerable

(

11.84

),

as do the repeated close-ups of newspaper photos of his frightened eyes. When the accusers state their case, Morris keeps us on Adams’s side by letting him rebut them. In segment 9, Adams replies to Harris’s charge that he was the shooter; in segment 15, Adams presents his alibi in reply to Harris’s claims about the time frame of events. By the end, Adams becomes the authoritative commentator. In segment 28, after Harris has committed another murder, Adams reminds us that a life could have been saved if the Dallas police hadn’t released Harris. At this point, our sympathies for Adams are strong, and we understand why he reverses his initial judgment on Dallas: it’s now “hell on earth.”

11.84 While Harris the teenager is associated with popcorn, Adams the panicked victim is associated with an ashtray full of cigarettes.

Our acceptance of Adams’s account is subtly reinforced by the many reenactments of the murder. They are clearly set off as reconstructions by their use of techniques more closely associated with the fiction film, particularly film noir (

11.85

; also

10.6

). They also distinguish themselves from the restagings shown on true-crime television shows, which tend to include the faces of actors and which are usually shot in a loose, hand-held style suggesting that we are witnessing the real event.

11.85 An echo of film noir: in a reenactment, Officer Wood is shown approaching the car.