B0041VYHGW EBOK (141 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Some of the most basic types of films line up as distinct alternatives. We commonly distinguish documentary from fiction, experimental films from mainstream fare, and animation from live-action filmmaking. In all these cases, we make assumptions about how the material to be filmed was chosen or arranged, how the filming was done, and how the filmmakers intended the finished work to affect the spectator.

Chapter 3

, on narrative form, drew its examples principally from fictional, live-action cinema. Now we’ll explore these other important types of films.

Before we see a film, we nearly always have some sense whether it is a documentary or a piece of fiction. Moviegoers entering theaters to view

March of the Penguins

expected to see real birds in nature, not wisecracking caricatures like the penguins in

Madagascar.

What justifies our assumption that a film is a documentary? For one thing, a documentary typically comes to us identified as such—by its title, publicity, press coverage, word of mouth, and subject matter. This labeling leads us to expect that the persons, places, and events shown to us exist and that the information presented about them will be trustworthy.

Every documentary claims to present factual information about the world, but the ways in which this can be done are just as varied as for fiction films. In some cases, the filmmakers are able to record events as they actually occur. For example, in making

Primary,

an account of John Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey campaigning for the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination, the camera operator and sound recordist were able to closely follow the candidates through crowds at rallies (

5.134

). But a documentary may convey information in other ways as well. The filmmaker might supply charts, maps, or other visual aids. In addition, the documentary filmmaker may stage certain events for the camera to record.

It’s worth pausing on this last point. Some viewers tend to suspect that a documentary is unreliable if it manipulates the events that are filmed. It is true that, very often, the documentary filmmaker records an event without scripting or staging it. For example, in interviewing an eyewitness, the documentarist typically controls where the camera is placed, what is in focus, and so on; the filmmaker likewise controls the final editing of the images. But the filmmaker doesn’t tell the witness what to say or how to act. The filmmaker may also have no choice about setting or lighting.

Still, both viewers and filmmakers regard some staging as legitimate in a documentary if the staging serves the larger purpose of presenting information. Suppose you are filming a farmer’s daily routines. You might ask him or her to walk toward a field in order to frame a shot showing the whole farm. Similarly, the cameraman who is the central figure in Dziga Vertov’s documentary

Man with a Movie Camera

is clearly performing for Vertov’s camera

(

10.1

).

10.1 Although the central figure of

Man with a Movie Camera

is a real cinematographer, his actions were staged.

“There are lots of in-between stages from shooting to public projection—developing, printing, editing, commentary, sound effects, music. At each stage the effect of the shot can be changed but the basic content must be in the shot to begin with.”

— Joris Ivens, documentary filmmaker

In some cases, staging may intensify the documentary value of the film. Humphrey Jennings made

Fires Were Started

during the German bombardment of London in World War II. Unable to film during the air raids, Jennings found a group of bombed-out buildings and set them afire. He then filmed the fire patrol battling the blaze

(

10.2

).

Although the event was staged, the actual firefighters who took part judged it an authentic depiction of the challenges they faced under real bombing. Similarly, after Allied troops liberated the Auschwitz concentration camp near the end of World War II, a newsreel cameraman assembled a group of children and had them roll up their sleeves to display the prisoner numbers tattooed on their arms. This staging of an action arguably enhanced the film’s reliability.

10.2 A staged blaze in

Fires Were Started.

Staging events for the camera, then, need not consign the film to the realm of fiction. Regardless of the details of its production, the documentary film asks us to assume that it presents trustworthy information about its subject. Even if the filmmaker asks the farmer to wait a moment while the camera operator frames the shot, the film suggests that the farmer’s morning visit to the field is part of the day’s routine, and it’s this suggestion that is set forth as reliable.

As a type of film, documentaries present themselves as factually trustworthy. Still, any one documentary may not prove reliable. Throughout film history, many documentaries have been challenged as inaccurate. One controversy involved Michael Moore’s

Roger and Me.

The film presents, in sequences ranging from the heartrending to the absurd, the response of the people of Flint, Michigan, to a series of layoffs at General Motors plants during the 1980s. Much of the film shows inept efforts of the local government to revive the town’s economy. Ronald Reagan visits, a television evangelist holds a mass rally, and city officials launch expensive new building campaigns, including AutoWorld, an indoor theme park intended to lure tourists to Flint.

No one disputes that all these events took place. The controversy arose when critics claimed that

Roger and Me

leads the audience to believe that the events occurred in the

order

in which they are shown. Ronald Reagan came to Flint in 1980, the TV evangelist in 1982; AutoWorld opened in 1985. These events could not have been responses to the plant closings shown early in the film because the plant closings started in 1986. Moore altered the actual chronology, critics charged, in order to make the city government look foolish.

Moore’s defense is discussed in “Where to Go from Here” at the end of this chapter. The point for our purposes is that his critics accused his film of presenting unreliable information. Even if this charge were true, however,

Roger and Me

would not therefore turn into a fiction film. An unreliable documentary is still a documentary. Just as there are inaccurate and misleading news stories, so there are inaccurate and misleading documentaries.

A documentary may take a stand, state an opinion, or advocate a solution to a problem. As we’ll see shortly, documentaries often use rhetoric to persuade an audience. But, again, simply taking a stance does not turn the documentary into fiction. In order to persuade us, the filmmaker marshals evidence, and this evidence is put forth as being factual and reliable. A documentary may be strongly partisan, but as a documentary, it nonetheless presents itself as providing trustworthy information about its subject.

Like fiction films, documentaries fall into genres. One common documentary genre is the

compilation

film, produced by assembling images from archival sources.

The Atomic Cafe

compiles newsreel footage and instructional films to suggest how 1950s American culture reacted to the proliferation of nuclear weapons

(

10.3

).

The

interview,

or

talking-heads,

documentary records testimony about events or social movements.

Word Is Out

consists largely of interviews with lesbians and gay men discussing their lives.

10.3 Older documentary footage of protective gear incorporated into

The Atomic Cafe.

The

direct-cinema

documentary characteristically records an ongoing event as it happens, with minimal interference by the filmmaker. Direct cinema emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, when portable camera and sound equipment became available and allowed films such as

Primary

to follow an event as it unfolds. For this reason, such documentaries are also known as

cinéma-vérité,

French for “cinema-truth.” An example is

Hoop Dreams,

which traces two aspiring basketball players through high school and into college.

Another common type is the

nature

documentary, such as

Microcosmos,

which used magnifying lenses to explore the world of insects. The Imax format has spawned numerous nature documentaries, such as

Everest

and

Galapagos.

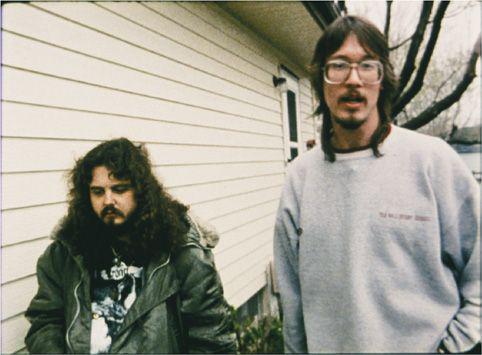

With increasingly unobtrusive, lightweight equipment becoming available, the

portrait

documentary has also become prominent in recent years. This type of film centers on scenes from the life of a compelling person. Terry Zwigoff recorded the eccentricities of underground cartoonist Robert Crumb and his family in

Crumb.

In

American Movie,

Chris Smith followed the difficulties of a Milwaukee film-maker struggling with budgetary problems and amateur actors to make a horror film

(

10.4

).

10.4 Filmmaker Mark Borchardt and his friend Mike (on left) freely discussed their lives and projects with Chris Smith for

American Movie.