B0041VYHGW EBOK (138 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

Other conventions follow from this one. Our reaction to the monster may be guided by other characters who react to it in the properly horrified way. In

Cat People

(1942), a mysterious woman can, apparently, turn into a panther. Our revulsion and fear are confirmed by the reaction of the woman’s husband and his coworker

(

9.14

).

In contrast, we know that

E.T.

is not a horror film because, although the alien is unnatural, he is not threatening, and the children do not react to him as if he is.

9.14 A shadow and a character’s reaction suggest an offscreen menace in

Cat People.

The horror plot will often start with the monster’s attack on normal life. In response, the other characters must discover that the monster is at large and try to destroy it. (In some cases, as when a character is possessed by demons, others may seek to rescue him or her.) This plot can be developed in various ways—by having the monster launch a series of attacks, by having people in authority resist believing that the monster exists, or by blocking the characters’ efforts to destroy it. In

The Exorcist,

for example, the characters only gradually discover that Regan is possessed; after they realize this, they still must struggle to drive the demon out.

The genre’s characteristic themes also stem from the intended response. If the monster horrifies us because it violates the laws of nature we know, the genre is well suited to suggest the limits of human knowledge. It is probably significant that the skeptical authorities who must be convinced of the monster’s existence are often scientists. In other cases, the scientists themselves unintentionally unleash monsters through their risky experiments. A common convention of this type of plot has the characters concluding that there are some things that humans are not meant to know. Another common thematic pattern of the horror film plays on fears about the environment, as when nuclear accidents and other human-made disasters create mutant monsters like the giant ants in

Them!

Not surprisingly, the iconography of the horror film includes settings where monsters might be expected to lurk. The old dark house where a group of potential victims gather was popularized by

The Cat and the Canary

in 1927 and has been used recently for

The Haunting

(1999) and

The Others

(2001;

9.15

). Cemeteries can yield the walking dead; scientists’ laboratories, the artificial human (as in

Frankenstein

). Filmmakers have played off these conventions cleverly, as when Hitchcock juxtaposed a mundane motel with a sinister, decaying mansion in

Psycho,

or when George Romero had humans battle zombies in a shopping mall in

Dawn of the Dead.

The slasher subgenre has made superhuman killers invade everyday settings such as summer camps and suburban neighborhoods.

9.15 An ominous high-angle framing in

The Others,

as the heroine hears a mysterious sound in the room above.

Heavy makeup is unusually prominent in the iconography of horror. A furry face and hands can signal transformation into a werewolf, while shriveled skin indicates a mummy. Some actors have specialized in transforming themselves into many frightening figures. Lon Chaney, who played the original Phantom in

The Phantom of the Opera

(1925), was known as “the man of a thousand faces.” Boris Karloff’s makeup as Frankenstein’s monster in

Frankenstein

(1930) rendered him so unrecognizable that the credits of his next film informed viewers that it featured the same actor. More recently, computer special effects have supplemented makeup in transforming actors into monsters.

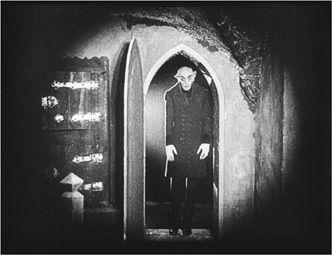

Like the Western, the horror film emerged in the era of silent moviemaking. Some of the most important early works in the genre were German—notably,

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

(1920) and

Nosferatu

(1922), the first adaptation of the novel

Dracula.

The angular performances, heavy makeup, and distorted settings characteristic of German Expressionist cinema conveyed an ominous, supernatural atmosphere

(

9.16

).

9.16 In

Nosferatu,

Max Schreck’s makeup and acting make his Count Orlock eerily like a rat or a bat.

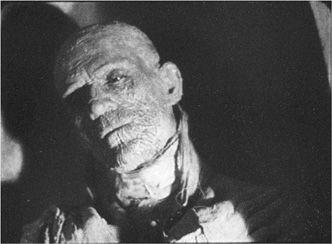

Because a horror film can create its emotional impact with makeup and other low-technology special effects, the horror genre has long been favored by low-budget filmmakers. During the 1930s, a secondary Hollywood studio, Universal, launched a cycle of horror films.

Dracula

(1931),

Frankenstein

(1931), and

The Mummy

(1932;

9.17

) proved enormously popular and helped the studio become a major company. A decade later, RKO’s B-picture unit under Val Lewton produced a cycle of literate, somber films on minuscule budgets. Lewton’s directors proceeded by hints, keeping the monster offscreen and cloaking the sets in darkness. In

Cat People,

for instance, we never see the heroine transform herself into a panther, and we only glimpse the creature in certain scenes. The film achieves its effects through shadows, offscreen sound, and character reaction (

9.14

).

9.17 A tiny gleam reflected in Boris Karloff’s eye signals the moment when the monster revives in

The Mummy.

“Our formula is simple. A love story, three scenes of suggested horror and one of actual violence. Fadeout. It’s all over in less than 70 minutes.”

— Val Lewton, producer,

Cat People

In later decades, other low-budget filmmakers were drawn to the genre. Horror became a staple of 1960s U.S. independent production, with many films targeted at the teenage market. Similarly, George Romero’s

Night of the Living Dead

(1968) was budgeted at only $114,000, but its success on college campuses made it hugely profitable.

The Blair Witch Project

(1999), shot for a reputed $35,000, found an even bigger audience internationally. Low-budget horror remains a profitable genre, with

Cabin Fever

and the

Saw

and

Hostel

franchises drawing large audiences in theaters and on DVD.

During the 1970s, the genre acquired a new respectability, chiefly because of the prestige of

Rosemary’s Baby

(1968) and

The Exorcist

(1973). These films innovated by presenting violent and disgusting actions with unprecedented explicitness. When the possessed Regan vomited in the face of the priest bending over her, a new standard for horrific imagery was set.

The big-budget horror film entered into a period of popularity that has not yet ended. Many major Hollywood directors have worked in the genre, and several horror films—from

Jaws

(1975) and

Carrie

(1976) to

The Sixth Sense

(1999) and

The Mummy

(1999)—have become huge hits. The genre’s iconography pervades contemporary culture, decorating lunch boxes and theme park rides. Horror classics have been remade (

Cat People, Dracula

), and the genre conventions have been parodied (

Young Frankenstein, Beetlejuice

).

The horror film has sustained an audience for over 30 years, and its longevity has set scholars looking for cultural explanations. Many critics suggest that the 1970s subgenre of family horror films, such as

The Exorcist

and

Poltergeist,

reflects social concerns about the breakup of American families. Others suggest that the genre’s questioning of normality and traditional categories is in tune with both the post-Vietnam and the post–Cold War eras: viewers may be uncertain of their fundamental beliefs about the world and their place in it. The continuing popularity of the teen-oriented slasher films from the 1980s to the present might reflect young people’s fascination with and simultaneous anxieties about sexuality and violence. Fans are also drawn by the sophisticated special effects and makeup, so filmmakers compete to show ever gorier and more grotesque imagery. For all these reasons, horror-film conventions grew so pervasive that parodies such as the

Scary Movie

franchise and

Shaun of the Dead

became as popular as the films they mocked. Through genre mixing and the give-and-take between audience tastes and filmmakers’ ambitions, the horror film has displayed that balance of convention and innovation basic to any genre.

“[Producer Arthur Freed] came to me and said, ‘What are you going to do with it?’ I said, ‘Well, Arthur, I don’t know yet. But I do know I’ve gotta be singing and it’s gotta be raining.’ There was no rain in that picture up to then.”

— Gene Kelly, actor/choreographer, on

Singin’ in the Rain

If the Western was largely based on the subject matter of the American frontier, and the horror film on the emotional effect on the spectator, the musical came into being in response to a technical innovation. Though there had been occasional attempts to synchronize live vocal and musical accompaniment to scenes of singing and dancing during the silent era, the notion of basing a film on a series of musical numbers did not emerge until the late 1920s with the successful introduction of recorded sound tracks. One of the earliest features to include the human voice extensively was

The Jazz Singer

(1927), which contained almost no recorded dialogue but had several songs.

At first, many musicals were

revues,

programs of numbers with little or no narrative linkage between them. Such revue musicals aided in selling these early sound films in foreign-language markets, where spectators could enjoy the performances even if they could not understand the dialogue and lyrics. As subtitles and dubbing solved the problem of the language barrier, musicals featured more complicated story lines. Filmmakers devised plots that could motivate the introduction of musical numbers.