B0041VYHGW EBOK (131 page)

Authors: David Bordwell,Kristin Thompson

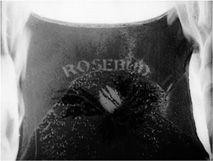

8.22 … moves down to center on Kane’s sled.

8.23 Another forward camera movement brings the sled into close-up.

After our glimpse of the sled, however, the film reverses the pattern. A series of shots linked by dissolves leads us back outside Xanadu, the camera travels down to the “No Trespassing” sign again, and we are left to wonder whether this discovery really provides a resolution to the mystery about Kane’s character. Now the beginning and the ending echo each other explicitly.

Our study of

Citizen Kane

’s organization in

Chapter 3

also showed that Thompson’s search was, from the standpoint of narration, a complex one. At one level, our knowledge is restricted principally to what Kane’s acquaintances know. Within the flashbacks, the style reinforces this restriction by avoiding crosscutting or other techniques that would move toward a more unrestricted range of knowledge. Many of the flashback scenes are shot in fairly static long takes, strictly confining us to what participants in the scene could witness. When the youthful Kane confronts Thatcher during the

Inquirer

crusade, Welles could have cut away to the reporter in Cuba sending Kane a telegram or could have shown a montage sequence of a day in the life of the paper. Instead, because this is Thatcher’s tale, Welles handles the scene in a long take showing Kane and Thatcher in a face-to-face standoff, which is then capped by a close-up of Kane’s cocky response.

We have also seen that Kane’s narrative requires us to take each narrator’s version as objective within his or her limited knowledge. Welles reinforces this by avoiding shots that suggest optical or mental subjectivity. (Contrast Hitchcock’s optical point-of-view angles in

The Birds

and

Rear Window,

pp. 224

–225 and

244

–

245

.)

Welles also uses deep-focus cinematography that yields an external perspective on the action. The shot in which Kane’s mother signs her son over to Thatcher is a good example. Several shots precede this one, introducing the young Kane. Then there is a cut to what at first seems a simple long shot of the boy

(

8.24

).

But the camera tracks back to reveal a window, with Kane’s mother appearing at the left and calling to him

(

8.25

).

Then the camera continues to track back, following the adults as they walk to another room

(

8.26

).

Mrs. Kane and Thatcher sit at a table in the foreground to sign the papers, while Kane’s father remains standing farther away at the left, and the boy plays in the distance

(

8.27

).

8.24 A progressively deeper shot in

Citizen Kane

begins as a long shot of the young Kane …

8.25 … becomes an interior view as the camera reveals a window …

8.26 … and moves backward with Mrs. Kane …

8.27 … keeping the boy in extreme long shot throughout the rest of the scene.

Welles eliminates cutting here. The shot becomes a complex unit unto itself, like the opening of

Touch of Evil

discussed on

pp. 216

–

217

. Most Hollywood directors would have handled this scene in shot/reverse shot, but Welles keeps all of the implications of the action simultaneously before us. The boy, who is the subject of the discussion, remains framed in the distant window through the whole scene; his game leads us to believe that he is unaware of what his mother is doing.

The tensions between the father and the mother are conveyed not only by the fact that she excludes him from the discussion at the table but also by the overlapping sound. His objections to signing his son away to a guardian mix in with the dialogue in the foreground, and even the boy’s shouts (ironically, “The Union Forever!”) can be heard in the distance. The framing also emphasizes the mother in much of the scene. This is her only appearance in the film. Her severity and clamped-down emotions help motivate the many events that follow from her action here. We have had little introduction to the situation prior to this scene, but the combination of sound, cinematography, and mise-en-scene conveys the complicated action with an overall objectivity.

Every director directs our attention, but Welles does so in unusual ways.

Citizen Kane

offers a good example of how a director can choose between alternatives. In the scenes that give up cutting, Welles cues our attention by using deep-space mise-en-scene (figure behavior, lighting, placement in space) and sound. We can watch expressions because the actors play frontally (

8.27

). In addition, the framing emphasizes certain figures by putting them in the foreground or in dead center

(

8.28

).

And, of course, our attention bounces from one character to another as they speak lines. Even if Welles avoids the classical Hollywood shot/reverse shot in such scenes, he still uses film techniques to prompt us to make the correct assumptions and inferences about the story’s progression.

8.28 Depth and centering in

Citizen Kane.

Citizen Kane

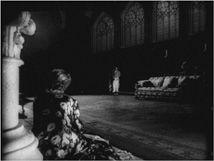

’s narration also embeds the narrators’ objective but restricted versions within broader contexts. Thompson’s investigation links the various tales, so we learn substantially what he learns. Yet he must not become the protagonist of the film, for that would remove Kane from the center of interest. Welles makes a crucial stylistic choice here. By the use of low-key selective lighting and patterns of staging and framing, Thompson is made virtually unidentifiable. His back is to us, he is tucked into the corner of the frame, and he is usually in darkness. The stylistic handling makes him the neutral investigator, less a character than a channel for information.

More broadly still, we have seen that the film encloses Thompson’s search and each narrator’s recollection within a more omniscient narration. Our discussion of the opening shots of Xanadu is relevant here: film style is used to convey a high degree of non-character-centered knowledge. But when we enter Kane’s death chamber, the style also suggests the narration’s ability to plumb characters’ minds. We see shots of snow covering the frame (for example,

8.29

), which hint at a subjective vision. Later in the film, the camera movements occasionally remind us of the broader range of narrational knowledge, as in the first version of Susan’s opera premiere, shown during Leland’s story in segment 6. There the camera moves to reveal something neither Leland nor Susan could know about

(

8.30

–

8.32

).

The final sequence, which at least partially solves the mystery of “Rosebud,” also uses a vast camera movement to give us an omniscient perspective. The camera cranes over objects from Kane’s collection, moving forward in space but backward through Kane’s life to concentrate on his earliest memento, the sled. A salient technique again conforms to pattern by giving us knowledge no character will ever possess.