Augustus (48 page)

Authors: Anthony Everitt

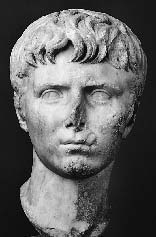

Augustus and Agrippa at the height of their powers. These marble busts were carved in the 20s

B.C.

They are realistic character studies that illustrate the two men’s different personalities—the one astute and calculating and the other energetic and determined.

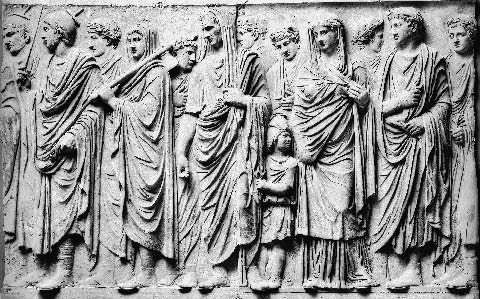

The tall man in the center of this relief has been identified as Agrippa. His head is veiled in his capacity as a priest attending a ritual sacrifice. In front of him walk two religious officials, the

flamines diales,

with their pointed hats, and a

lictor,

or ceremonial guard, carrying the

fasces,

an ax inside a bundle of rods. The little boy holding onto his toga may be either his son Gaius or Lucius. The boy is looking back toward his mother, Julia. The man walking behind her is probably Mark Antony’s son Iullus Antonius, later to become Julia’s lover. The stone carving comes from the

Ara Pacis Augustae,

or Altar of Augustan Peace. Inspired by the friezes on the Parthenon, it was dedicated in 9

B.C.

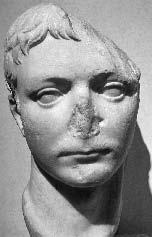

A contemporary portrait of Tiberius as a young man setting out on a distinguished career as soldier and public servant.

Young Gaius Caesar, Agrippa’s son by Augustus’ daughter Julia, whom the

princeps

adopted and groomed as his successor. The marble bust dates from about the time of his consulship in 1

B.C.

or during his eastern mission.

Agrippa’s last son, Agrippa Postumus, born after his father’s premature death in 12

B.C.

The contemporary sculptor has captured a sense of danger and intensity in his youthful subject.

This onyx cameo, the

Gemma Augustea,

is an example of mendacious art at its finest. Made in

A.D.

10 the seventy-three-year-old

princeps

is presented as a half-naked youth. He is seated next to a personification of Rome, beside whom stands Augustus’ grandson Germanicus. On the left Tiberius alights from a chariot. Beneath is a scene of defeated and humbled barbarians. The overall impression is of serenity and success. In fact, the mood at Rome was nervous and gloomy, for Augustus was just recovering from the greatest threat to his authority during his long reign, the loss of three legions destroyed in an ambush in Germany the previous year.

A fresco of an actor’s mask from a room in Augustus’ house on the Palatine Hill, which may have been his bedroom. The

princeps

enjoyed theater and, to judge by his last words, saw himself as a performer. He asked the people around his bedside: “Have I played my part in the farce of life well enough?”

This image of Augustus is a majestic statement in stone of his

imperium

and

auctoritas,

his power and authority. Probably made in

A.D.

15, the year after his death, it shows him as a beautiful young man, whose ageless features combine aspects of his actual appearance and the classic lineaments of the god Apollo, Augustus’ favorite in the Olympian pantheon. Found at his wife Livia’s villa at Prima Porta outside Rome.

XXI

GROWING THE EMPIRE

17–8

B.C.

As so often, it is as well to look below the surface of what the

princeps

said to what he exactly did. At bottom, he was an aggressive imperialist. Under his rule, Rome gained more new territory than in any comparable period in its previous history. His real position is set out in his official autobiography,

Res Gestae,

where he boasts: “I enlarged the territory of all provinces of the Roman People on whose borders were people who were not yet subject to our

imperium

.”

Public opinion expected nothing less of Rome’s ruler. Republican law had forbidden the Senate to declare war without provocation, without a casus belli, and indeed Rome (like Great Britain two millennia later) had acquired much of its eastern empire without altogether intending to do so. But now the idea that Rome had an imperial destiny was one of the ways by which the regime justified itself in the public mind.

Virgil writes of a Caesar “whose empire / shall reach to the Ocean’s limits, whose fame shall end in the stars”; Horace begs the goddess of luck to “guard our young swarm of warriors on the wing now / to spread the fear of Rome / into Arabia and the Red Sea coasts.”

The phrase “Ocean’s limits” reminds us how small and fuzzy at the edges was the Roman world. Accurate navigational equipment not having been invented, most explorers—usually they were traders—did not travel very far from the Mediterranean.

The Romans believed that the world’s landmass was a roughly circular disk consisting only of Europe and Asia, and that it was surrounded by a vast expanse of sea, Oceanus. They had no idea that the American and Australasian continents existed, nor that there was land beyond India. The landmass itself surrounded the Mediterranean Sea and Greece and Italy. The island of Britannia perched on its northwestern edge. The Roman empire took up a large part of the world as its inhabitants believed that world to be, and it was very tempting for its ambitious rulers to dream that they might one day conquer it all.

Maps were rare in the classical time; the first known world maps appeared in fifth-century Athens. Borrowing from Alexandrian models, the Romans, with their imperial responsibilities, recognized the practical importance of cartography. A world map was commissioned by Julius Caesar, probably as part of a triumphal monument he built on the Capitoline Hill, which showed him in a chariot with the world, in the form of a globe, at his feet.

Augustus commissioned his deputy, Agrippa, to work on a more detailed map, the

orbis terrarum

or “globe of the earth.” This showed hundreds of cities linked by Rome’s network of roads; it was based on reports sent in by Roman generals and governors, and by travelers. The result was a broadly recognizable picture, although distances and shapes became less and less accurate the farther places were from Rome.

The main purpose of the map was as an aid for imperial administrators, provincial governors, and military commanders; as a visual representation of the empire, it was also a powerful metaphor of Roman power. The map was painted or engraved on the wall of the Porticus Vipsania, a colonnade built by Agrippa’s sister, and was on permanent public display. Copies on papyrus or parchment were made for travelers, or information copied down.

As we have seen, Augustus and Agrippa spent many years abroad in different corners of the empire. Between 27 and 24

B.C.

, the

princeps

was in Gaul and Spain; between 22 and 19

B.C.

in Greece and Asia; and between 16 and 13

B.C.

in Gaul. Meanwhile, Agrippa spent 23 to 21

B.C.

in the east, 20 and 19 in Gaul and Spain, and 16 to 13

B.C.

in the east again. They spent their time quelling revolts, reforming or reviewing local administrations, and, above all, superintending the consolidation and expansion of the empire.

It is hard to tell whether the two men reacted to circumstances as they arose or pursued a long-term strategy. The impression is given of an orderly progression in the years that followed Actium from one priority to another. As we have seen, the eastern provinces and client kingdoms were reorganized. The frontier of Egypt was pushed southward and contact was made with the Ethiopians. An attempt was made to conquer the Arabian Peninsula, which failed. The negotiations with the Parthians were brought to a successful conclusion. Gaul and Spain were pacified.