Atlantis and the Silver City (29 page)

Read Atlantis and the Silver City Online

Authors: Peter Daughtrey

(

IMAGE

40

B

)

(

IMAGES

40

A AND

40

B

)

Charts of the Algarve’s “Southwestern Alphabet” compared with a few of the discoveries of other ancient alphabets. Note that many characters are identical or very similar. They span many thousands of years between them, and they all predate the Phoenician alphabet shown on the right

. (Courtesy of Carlos Castelo.)

Pre-1600

B.C.

Yet another of Carlos’s charts demonstrates the startling similarity between the ancient Iberian characters and those found from the Minoan civilization on Crete. I suggested earlier that the Minoan civilization could have sprung from resurgent remnants of Atlantis. The presence on Crete of remnants of this ancient alphabet, which seems to have originated in the area of the Atlantis homeland, would certainly support this theory and might explain why the Minoans were so adept at maritime activities. Plato said that Atlantis ruled through the whole of the Mediterranean as far as Egypt. It would therefore have included Crete and Santorini.

Samples with some characters matching those from the Algarve and Moroccan script (ancient Libyan) have been discovered on the Canary Islands of Hierro and Grand Canary by Dr. René Verneau.

92

Elena Wishaw pointed out the similarity of ancient letters she had found in and around Niebla and Seville to ancient Libyan and Viking runes. When she was conducting her research in the 1920s, the Algarve specimens had not yet come to light, but many of the letters tabulated in her book are the same as, or similar to, the Algarve script.

Scandinavian and German Runes

An assistant in an Algarve museum told me how a visitor from Ireland, confronted by an example on display there, exclaimed in astonishment that at first he thought he was looking at ancient Irish. I have not been able to trace any old Irish script that is sufficiently similar, but Dublin became a Viking city and he may well have been confusing the characters with Viking runes.

Dr. Roger Coghill, who devotes a chapter to the script on his CD “The Atlantis Effect,” points out that Viking runes, known as “the younger Futharc,” comprise sixteen characters, four of which are the same as the Algarve script.

93

He also perceptively observes that the runes are less sophisticated, probably so they can all be created by chiseling straight lines; there are no curves or circles. The Viking script was preceded by “the German Futharc,” which had twenty-four characters. Perhaps the Germans and Scandinavians were reinventing remnants or memories of the original in a form that could easily be carved.

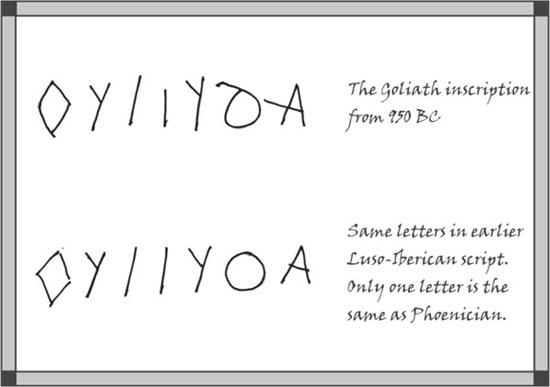

950

B.C.

Over the years, I have put together several vital pieces of exclusive evidence. Unless you were interested in—and familiar with—the Algarve script, you would not have noticed their significance. The first appeared in a news item in the world press in November 2005. I saved a half-page editorial from the English

Daily Mail

dated November 12, written by Julie Wheldon, the newspaper’s science correspondent. The headline was

GOLIATH, THE PROOF.

The article was accompanied by a photograph of a seven-character inscription on a shard of pottery found by Israeli archaeologists at a site in southern Israel. The site is thought to have been a Philistine city named Gath. According to the Bible, this was the home of Goliath, the Philistine giant, famously slain by David using just a stone propelled from a slingshot. After extensive research, the excavation director, Professor Aren Maeir, concluded that the letters related to the name Aylattes, which is thought to be the Philistine name for Goliath. The latter is an Israeli version. The find was in the right place and dated back to the correct period: 950

B.C.

Maeir consequently claimed it was the first real evidence proving that there was a “historic kernel to the biblical tale.”

It was a fascinating story, and it is easy to appreciate why the

Daily Mail

devoted half a page to it. What particularly intrigued me, though, was that I immediately recognized the letters as being identical to those in the old Algarve script.

The article pointed out that the Philistines are believed to have ended up in Israel about 1200

B.C.

, complete with their own language and culture.

On analysis, I discovered that several of the letters on the pottery shard are not in the Phoenician alphabet, yet they are in the Algarve script. So the extra Iberian characters already existed. What were they doing in Israel? How did the Philistines come by the script? This is critical, indisputable evidence and supports Carlos Castelo’s conclusions. (

SEE IMAGE

41,

NEXT PAGE

.)

As the inscription has been identified by the archaeologists as being of an older Proto-Canaanite script predating Phoenician, logically the identical Algarve script is older too. Interestingly, the Phoenician alphabet is also thought to have developed from an old Proto-Canaanite language—in existence around 1050

B

.

C

.

(

IMAGE

41)

The characters on the “Goliath” shard, compared with the ancient Algarve “Southwestern Script.”

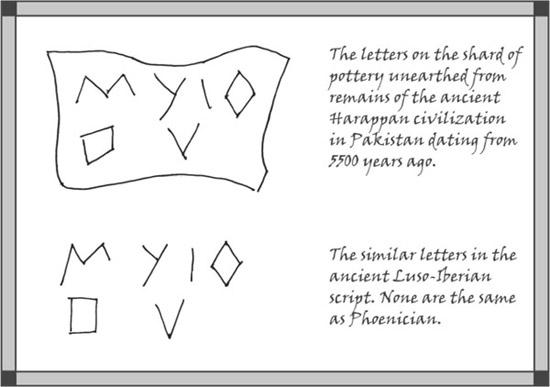

3500

B.C.

The other example is from a piece of broken pottery collected from a site in Pakistan or India. I originally spotted it on the BBC web site, where it was used to illustrate broken pottery brought up from the remains of an approximately 10,000

B.C.

submerged city off the coast of India in the Gulf of Cambay (as discussed in an earlier chapter). The discovery was made while surveying the area where an ancient large river mouth would have been above water before the final inundation at the end of the glacial period. (

SEE IMAGE

42,

NEXT PAGE

.)

The piece of pottery had a form of decoration that is too random to be artistic but strongly resembles the ancient Algarve script, the samples found by Mrs. Wishaw around Niebla, and ancient Libyan. Three of the five characters are the same, and the others are similar.

(

IMAGE

42)

A drawing of the 5,500-year-old piece of decorated pot unearthed in a Harappan city in Pakistan, compared with the same letters in the Algarve “Southwestern Script.” It dates from over 2,000 years before the Phoenicians even existed, and none of the letters are the same as the Phoenician alphabet

.

Further research on the BBC site revealed the same photograph popping up to illustrate finds made recently in a 3500

B.C.

Pakistani city from the Harappan civilization. I have not been able to ascertain which it relates to, although I suspect it is the latter, but in a way it doesn’t much matter. Both sites are far older than Phoenician, Greek, and even the accepted dates that historians stubbornly maintain for Egyptian civilization. This considerably extends the area of influence for this enigmatic alphabet. One cannot rule out that the pottery arrived at the site as a result of trade, but then that does not affect its age. Maybe the inscription reads “a souvenir from Atlantis” (tongue in cheek).

Some scholars have suggested that Phoenician was the model for scripts developed in such far-flung places as Southeast Asia, Tibet, Mongolia, and, particularly, the Brahmin script of India. The date of the pottery

shard shown on the BBC web site contradicts that and shifts the spotlight onto the Algarve script. The Phoenicians did not even exist then—yet the Algarve script bears distinct similarities to the inscription, so it was apparently known in the Indian subcontinent at that time.

Anyone who begins to research old civilizations and legends will quickly come across assertions that the whole world once spoke the same language and used the same alphabet. Bearing this out, far afield in the opposite direction from India, samples of the alphabet have been found in North America—the Grave Creek Tablet mentioned in the last chapter, for example. Elsewhere, the Spanish recorded a form of writing possessed by the Aymara Indians living on the shores of Lake Titicaca in South America. Some of the characters match others in the Southwestern Script.

94

Is there an echo here of the biblical account of the Tower of Babel, which begins by saying that originally the whole world had just one language and goes on to imply that this had enabled mortals to develop their civilizations and technology? Quoting from Genesis 11:1-9:

“But the Lord came down to see the city and the tower that the men were building. The Lord said: ‘If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. Come, let us go down and confuse their language so that they will not understand each other.’ So the Lord scattered them from there all over the earth, and they stopped building the city.”

Note that the Lord was not alone. He said “Come, let

us

go down.…” It also implies that man was becoming technologically advanced. The Tower of Babel is most likely a metaphor for this, and the biblical account, in a rather folksy way, hides the true nature of an event of truly disastrous proportions that almost annihilated that civilization just as it was acquiring the height of technology.

2500

B.C.

to 400

B.C.

Until a few years ago, most of the

herouns

discovered in the Algarve and engraved with the old script were scattered amongst local museums, with a few appropriated by others elsewhere in Portugal. Now a superb, purpose-built museum in a southern country town called Almodôvar has successfully gathered around twenty of them together. It is seen as a tourist attraction,

as several impressive

heroun

examples were found in that neighborhood. Unfortunately, the museum is adhering to the establishment view and, although they are all beautifully displayed, the samples are dated as being from the first millennium

B.C.

I questioned the museum authorities on this point, specifically asking on what evidence some original dates had been adjusted to more recent ones. I received no answers.

As many as forty letters, maybe more, have been identified in the local Algarve script; but, since it evolved over thousands of years, Carlos Castelo points out that many of the letters represent the same character, several times having evolved from one to the other. An example is a letter that looks like “Y,” which later became “X.”

The Phoenician alphabet has twenty-two characters, the Greek has twenty-four, and the Iberian sources vary from twenty-two to twenty-seven. Of the Algarve letters, eleven are the same as Greek and thirteen appear to be the same, or very similar, to Phoenician. If the local script had developed from Phoenician and Greek, why did the local people go to the trouble of developing so many new characters when they were already presented with completed alternatives? They certainly wouldn’t have done so for a few gravestones, and there is no evidence of its being used for more than that during the Phoenician era. The crude, uncraftsmanlike execution of the work suggests a relic language—largely forgotten, but perpetuated by a priestly class to impress its flocks for ceremonial purposes. In ancient times, the ability to read and write was often restricted to rulers and priests. It was used as an instrument of power and to inspire awe in the ordinary people.