Atlantis and the Silver City (24 page)

Read Atlantis and the Silver City Online

Authors: Peter Daughtrey

The stairways on each of the main complex of three were precisely aligned with the rise and fall of the sun on the summer solstice. Like the Egyptians, Guanches were sun worshippers. The archaeologist carried out test excavations on a ceremonial platform between two of them and confirmed that it had been built from stone blocks, gravel, and earth. The platforms on the tops of the pyramids were perfectly flat and consisted of gravel.

Heyerdahl was convinced they were the work of pre-European explorers, constructed in the same way as those found in South America and Mesopotamia.

No one knows for how long the Guanches inhabited the Canaries, but the popular theory is that they came from North Africa. Strangely, though, it is recorded that when the Spanish arrived, the locals did not possess boats. As a result, the various islands existed autonomously. Unless they had been dumped on the island by others, they must once have been capable of sea travel, but they had regressed and/or forgotten how to build boats. Maybe this was the result of the horrors of being stricken by huge tsunamis—resulting from the Algarve quakes—that had destroyed any boats they had and devastated low-lying areas? Perhaps they were just too terrified to put out to sea afterward?

If they were part of the Atlantis Empire, in the wake of the disaster striking their homeland they could suddenly have been left to fend for themselves without their knowledgeable ruling mentors. They were, however, intelligent; it would be surprising if they had not been able to work out how to build some sort of primitive seagoing vessel. Before the rise in sea levels, the islands would have been larger, and it has been postulated that some of them could have been joined together at some point in history. Any sudden sinking of land and rise in sea levels could also have contributed to the surviving inhabitants’ trepidation about venturing forth and braving the waves.

Sadly, as in South America, the Spaniards were not concerned with preserving the history of conquered lands, and the Guanches’ early history remains a mystery. Who knows what was destroyed by the religious

zealots amongst the Spaniards? A few examples of a long-forgotten script have survived and, significantly, a good percentage of the symbols are the same as those found in the Algarve, such as on the gravestone mentioned in Chapter One.

The Guanches resisted the Spanish for decades before succumbing. Those not put to the sword eventually intermarried with Spaniards, who were much taken by the extremely attractive Guanche women; but the odd throwback to the original gene pool can still be seen.

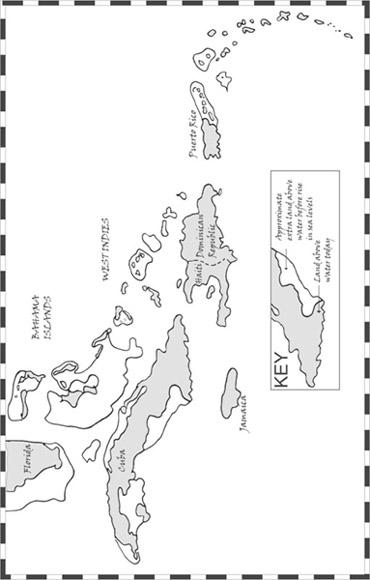

Leaving the Canaries, we may have charted a course north to Madeira, or possibly taken the Canary current, like Columbus, direct to the Caribbean.

The island of Madeira was uninhabited when discovered by the Portuguese around 1418

A.D.

Some people believe it was alluded to in various earlier Greek tales; but, apart from the following story about the Carthaginians, my researches suggest that no signs of earlier habitation have ever been found. It is an extremely precipitous island, with high mountains. One of the surprises for tourists is the ingenuity of the current Portuguese inhabitants in constructing terraces for cultivation on slopes steep enough to panic a mountain goat.

Classical writers have often described journeys by individuals to various legendary isles in the Atlantic Ocean. One account, generally associated with Madeira, is that by Pseudo-Aristotle. An impostor of the famous Aristotle, he was possibly one of his pupils. In one work,

On Marvelous Things Heard

, he refers to a “desert island” in the Atlantic outside the “Pillars of Hercules,” a few days’ voyage away.

71

According to him, it was discovered by Carthaginians, who established a colony there. They were so taken by it that they adopted the same tactics against any other nationality venturing too close as for those trying to navigate the Straits of Gibraltar: their boats were sunk and the occupants caught and summarily killed.

Interestingly, Pseudo-Aristotle reported that the island did have inhabitants but the Carthaginians had massacred them. He also said, however, that the island had large rivers but, despite reasonable rainfall, the mountainous landscape means that these are noticeably absent on Madeira today.

It was subject to volcanic activity up to around 6,500 years ago (4500

B.C.

).

72

If Plato’s figures were correct, that is 5,000 years after Atlantis was destroyed. When the sea levels were 100 to 120 meters lower, part of

Madeira from the Ponta de Sao Lourenço extended a significant distance above water toward another small group of uninhabited islands called Islas Desertas. So we appear to have at least one submerged area, much flatter than the rest of the island and perhaps more suited to habitation and cultivation.

Another ancient account was brought to my attention by Roger Coghill.

73

He had found it in the writings of the Sicilian Diodorus Siculus, who is probably better known for his account of the legendary Amazons, which also contains some illuminating comments referring to possible survivors from Atlantis. “There was once in the western parts of Libya, on the bounds of the inhabited world, a race ruled by women who practiced the arts of war.” He goes on to relate how the Amazons conquered a race called the Atlantoi, described by him as “most civilized men,” living in a prosperous country with great cities—and much given to astrology. He continues that in mythology, that country, along the shores of the ocean, was the birthplace of the gods. Does that sound familiar?

About a decade ago, a stone-lined grave was uncovered in the Algarve while a country road close to Silves was being repaired. It contained the skeleton of a woman warrior complete with spear. Elena Wishaw had a small cup in her museum in Niebla that was decorated with a picture of a woman warrior fighting two male warriors. All very intriguing, but, that aside, Diodorus talks of an island a number of days’ voyage to the west of the Libyan coast. For readers familiar with Madeira, his description of part of the island and its climate will strike a chord. “Its land is fruitful, much of it mountainous and not a little being a level plain of surpassing beauty. Through it flow navigable rivers which are used for irrigation, and the island contains many parks planted with trees of every variety and gardens in great multitudes which are traversed by sweet water; on it also are private villas of costly construction, and throughout the gardens banqueting houses have been constructed in a setting of flowers, and in them the inhabitants pass their time during the summer season.… There is excellent hunting of every manner of beast and wild animal.… And speaking generally, the climate of this island is so altogether mild that it produces in abundance the fruits of the trees and the other seasonal fruits of the year, so that it would appear

that the island, because of its exceptional felicity, were a dwelling place of gods and not of men.”

Today, Madeira is justifiably promoted as “The Garden Isle,” and “hotels” could be substituted for “banqueting houses” in the above account. The diversity of the trees, shrubs, and flowers that currently grow there is partly the result of the Portuguese discoverers, who dropped seeds off on their way back from the New World. There would not, however, be such a huge variety flourishing there without the extremely equable climate. The rivers allegedly encountered by the Carthaginians and described by Diodorus may have flowed on the now-submerged area; there is plenty of water on the island, but the land is too precipitous for many rivers to flow. When touring there a few years ago, to leave a small road tunnel we had to drive under a cascade of water. No need to find coins for a car wash there.

Strabo, the Greek writer already mentioned in an earlier chapter, quotes an earlier account from Poseidonius, another ancient chronicler, of practically the same legend Diodorus detailed, and says that the land was known to have changed its level there.

There is another, much smaller island a few hours’ boat trip away: Porto Santo. Its claim to fame is that a few years before Columbus sailed to discover America, he married the daughter of its Portuguese governor and lived there for a while. Intriguingly, his father-in-law was head of the “Order of Christ” in Portugal—a society previously called the Knights Templar, which changed its name in a ploy to be spared by the Portuguese king when the pope decreed that all members of the order be simultaneously murdered throughout Europe.

At the time, toward the end of the fifteenth century, the Order of Christ specialized in navigation. Henry the Navigator, the famous Portuguese (he was, in fact, half English) prince who instigated the great “Age of Discoveries,” was also a head of the order. It has long been speculated that Columbus obtained old maps from the order that showed the Atlantic and the Americas. Henry’s brother was also a cartographer and dealer in maps in Portugal’s capital, Lisbon.

The Turkish admiral Piri Reis added handwritten notes to his famous map discussed in the last chapter. One such note asserted that Columbus had obtained a book indicating that the Atlantic ended in a coast with

islands in front. Columbus’s own journal covering the first epic voyage indicates that he and Martin Pinzón, the captain of the caravel

Pinta

and his second-in-command, regularly consulted a chart passed back and forth between the boats. Apparently, the chart had islands marked on it.

Taking leave of his uncle, the young prince in the tale at the beginning of this chapter would have left Madeira and headed for the group of islands known as the Azores. These approach the halfway point between Europe and the Americas. It is thought that in ancient times they comprised more islands and that the existing ones were much larger. Today there are nine major islands.

The Piri Reis map shows sixteen islands, plus another one conveniently located midway between them and Madeira. The remnants of this could, perhaps, be the deserted Ilhas (islands) Selvagens. The current Azores islands were claimed for the Portuguese in 1427 when they were discovered by Diogo da Silves. None of them is of any great size. The largest, São Miguel, is about forty by ten miles and has boiling-hot springs. When we visited some twenty years ago, in the area around the springs a tourist attraction had been provided in the form of regularly lowering a large pot full of meat and vegetables into a narrow silo in the ground. On its removal a few hours later … dinner was ready, cooked by the intense underground heat.

There is no real evidence of previous habitation, but a hoard of Carthaginian coins was discovered in a black pot near the foundations of a destroyed building. More intriguingly, a stone statue of a horse and rider pointing to the west was found on the island of Corvo. Unfortunately, it was inadvertently broken by the men sent by the Portuguese king to retrieve it.

This statue was reported to have had an indecipherable inscription on the base. Confusion reigns over a statement in the same report that the inhabitants called the statue “Catés.” It does not clarify whether these inhabitants were on the island when it was discovered or were the recent new immigrants from Portugal. “Catés” resembles the Inca-Quechua word “Cati,” meaning “go that way” or “follow.” It is not a Portuguese word. Either the statue was imported there, or a civilization had developed a sophisticated culture with artisan skills. Sculpting such a statue would have required metal tools, and that meant mining, smelting, and casting. And what of the development of an alphabet for that inscription on the base?

This is the most volatile area of the entire Atlantic seabed, unique in that it is the meeting point of three continental plates: the North American, the European, and the African. It is from here that the fault line extends across to, and in front of, southwest Iberia.

Evidence from numerous geological expeditions indicates that areas of it had at some stage risen by as much as a thousand meters, exposing it above sea level. Then, many thousands of years later, it subsided by an incredible

six

thousand meters. Dr. René Malaise of the Riks Museum in Stockholm commented in 1957 that a colleague—Dr. R. W. Kolbe—had found evidence from a Swedish deep-sea expedition ten years earlier that indicated recent subsidence in the mid-Atlantic Ridge area; samples taken showed fossilized land plants and freshwater organisms. Earlier evidence was revealed in the U.S. Geological Survey of Deep Core Soundings in 1936, undertaken by Charles S. Piggot. It found heavy deposits of ash on underwater slopes dated to twelve thousand years ago. Commenting on this in 1944, Swedish oceanographer Hans Petterson wrote: “The topmost of the two volcanic strata is found above the topmost glacial stratum, which indicates that this volcanic catastrophe or catastrophes occurred in postglacial times. … It can, therefore, not be ruled out that the mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the samples originated, was above sea level up to about ten thousand years ago and did not subside to its present depth until later.” That at least parts of this area were above water for a considerable time seems incontrovertible. It could have been as one island or separate islands of which the Azores are remnants.

One possibility that cannot be discounted is that the Phoenicians and, later, the Carthaginians developed a port or base there to assist their trade with South America, as suggested in Chapter Three. Even earlier, the Minoans may have exploited the islands as a stopover point. It is obvious that, like Madeira and the homeland back in Iberia, any earlier civilization would have been subjected to particularly violent seismic activity. Habitation would inevitably have centered on the low-lying agricultural areas and the coast, the very regions that would have been inundated. Fierce fires, landslides, and volcanoes would have obliterated any settlements in the mountains. It is not surprising that when rediscovered by the Portuguese, the land was empty of humans.