Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse (50 page)

Read Assassination: The Royal Family's 1000-Year Curse Online

Authors: David Maislish

Tags: #Europe, #Biography & Autobiography, #Royalty, #Great Britain, #History

The other man was Victoria’s Scottish servant, John Brown, who saw to every need in her private life. He treated Victoria like a woman, rather than as a queen. The relationship was unpopular with the Royal Family and with the public, but it helped to drag Victoria back to some semblance of normality.

Victoria lost the support of Disraeli when he was replaced as Prime Minister by Gladstone, whose rapport with the Queen was uncomfortable because of his awkward manner and his lengthy speeches to her. Unfortunately, the Prince of Wales was not able to comfort his mother. She blamed him for the death of Albert, writing in a letter: “I never can, or shall, look at him without a shudder”.

Then, in 1871, Edward fell ill with typhoid, and Victoria hurried to his side. For a time Edward’s life was in the balance, but he recovered. Victoria attended the Thanksgiving Service at St Paul’s Cathedral, and the waiting crowds cheered her as she made her way through the city.

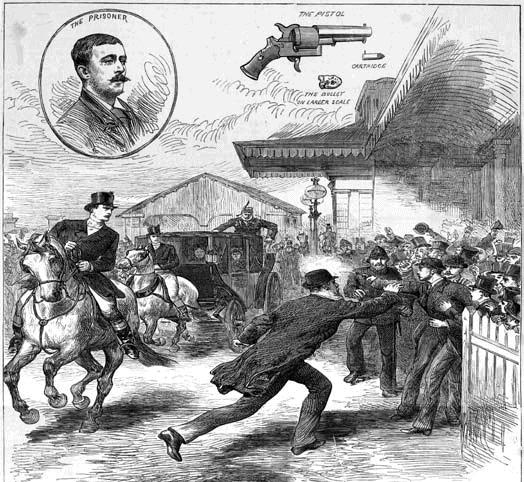

Two days later, as Victoria was entering the grounds of Buckingham Palace in her carriage, she was accosted by a young man who waved a pistol at her demanding the release of Irish prisoners. The man was Arthur O’Connor. John Brown seized O’Connor, who was taken away.

At his trial, O’Connor insisted on pleading guilty, despite his counsel producing several doctors who testified that he was insane. The jury found O’Connor to be “perfectly sane when he pleaded guilty to the indictment and perfectly sane now”. He was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment and 20 strokes of the whip. The Queen complained to Gladstone that O’Connor would be on the streets again within months, so a proposal was made and O’Connor agreed to go and live in Australia instead of the whipping. A year later he returned to England and was committed to Hanwell Asylum. Released after 18 months, he went back to Australia.

Now Victoria had been seen once more by her people, and there was sympathy because of the recent confrontation. The reconciliation with her subjects was complete. Although she continued to dress in black and to mourn for her beloved Albert, Victoria returned to public life. In 1874, it all became so much easier when Disraeli was once more appointed Prime Minister.

Then there was a bonus. The rulers of the Mughal dynasty had governed most of India, and they had used the titles ‘

Badshah

’ and ‘

Samrat

’, both of which translate to ‘Emperor’. They were deposed by the East India Company (which had been authorised by Britain to administer India), and the company steadily increased its area of control – when General Napier conquered Sindh, he reported his victory in the famous one word message and pun:

Pecavi

, Latin for ‘I have sinned’.

Although there were many grievances, the Indian Mutiny was sparked when the army introduced a new rifle cartridge that had to be bitten open. It was widely believed that the cartridges were greased with lard (pork fat) that was regarded as unclean by Muslim soldiers, or with tallow (beef fat) that was sacrilege to the Hindu soldiers – the instruction to bite the cartridges caused outrage. The East India Company put down the mutiny, but was then dissolved, and India became a British possession. Disraeli took the opportunity to revive the former rulers’ designation, and he presented Victoria with the title: ‘Empress of India’.

Victoria joined the Emperors of Russia, Austria and Germany, equal in rank. More importantly, it raised Victoria to the level her oldest daughter would attain when she became Empress of Germany eight years later; and it was now Germany rather than Prussia. Bismark, the Prime Minister of Prussia, had been determined to see to the unification of the German states under the leadership of Prussia, and to ensure that it would be an authoritarian regime. As a first step, Prussia invaded Schleswig, and agreed to Austria taking Holstein. Prussia then seized Holstein. Austria declared war, but was quickly defeated, and in the resultant treaty Prussia annexed Frankfurt, Hanover, Hesse-Kassel and Nassau.

The next issue for Bismark was that Crown Prince Frederick and his wife Victoria (Queen Victoria’s oldest child) were admirers of Britain’s constitutional monarchy and parliamentary system, so Bismark separated them from their son, the future Kaiser, to ensure that he would be brought up to believe in divine right and autocratic rule.

After victory in the Franco-Prussian war (provoked by Bismark), Prussia acquired Alsace and Lorraine. Eager to share in the victory, 25 German states, duchies and cities joined Prussia in the German Federation of which the King of Prussia was to be the Emperor. Bismark became Chancellor of the new empire, and as a strict Lutheran he introduced anti-Catholic legislation, which was followed by anti-socialist laws and severe curtailment of the freedom of the press.

Emperor William I died, but his successor Frederick’s reign lasted only three months. He was succeeded by his son William II, the Kaiser. However, the strong personalities of the Kaiser and Bismark led to conflict, and in 1890 the Kaiser demanded Bismark’s resignation. By then he had accomplished his aims. Before leaving office, Bismark predicted a war from Moscow to the Pyrenees and from the North Sea to Palermo. He wrongly thought it would be about Bulgaria (“a little country … far from being an object of adequate importance”) rather than Serbia, but correctly added that “At the end of the conflict we should scarcely know why we had fought.”

At home, Victoria had to deal with further tragedies. Her daughter, Alice, died in 1878 on the seventeenth anniversary of Albert’s death. In the following year, Waldemar, youngest son of Victoria’s first child, Princess Victoria, died; a poorly boy, he suffered from haemophilia. Then a turn for the better when Queen Victoria’s seventh child, Arthur, married Princess Louise of Prussia – Victoria joined the celebrations.

In 1880, Gladstone was reappointed Prime Minister when the Liberal Party took office. Two years later Disraeli died. Victoria had grown to detest Gladstone with his moralising sermons. She longed for Disraeli and his ambitions for the Empire. There was nothing she could do about it; Victoria was on her own, but now she could cope with the situation.

On 2nd March 1882, Victoria travelled by carriage to Windsor Railway Station. A large crowd was waiting to cheer the Queen as she arrived. Suddenly a man ran forward, raised a pistol and shot at Victoria. Yet again, the assassin missed. Scotsman Roderick MacLean was tried for treason. He had already spent time in various lunatic asylums. MacLean suffered from delusions of persecution combined with extreme anti-royalist views. It seems that he was angry because he had sent a poem to the Queen, and had received only a curt reply. Doctors produced by both the prosecution and the defence gave evidence that MacLean was insane. The jury took only five minutes to agree. MacLean was found ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’, and was sent for life to the new Broadmoor Hospital for the criminally insane.

Now Victoria had had enough. How could these people be found not guilty? “Insane he may have been, but not guilty he was most certainly not, as I saw him fire the pistol myself”, she complained bitterly. She was not impressed by the proposition that not knowing right from wrong, MacLean could not have formed a criminal intent. In accordance with Victoria’s demand, the law was changed so that in future the verdict

McClean’s assassination attempt

McClean’s assassination attemptwould be ‘guilty but insane’. The accused was still locked up in an asylum, but the verdict satisfied the Queen. The form of verdict would not be changed back to ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’ until 1964.

As time went by, Victoria became increasingly exasperated with Gladstone and his high moral tone and devotion to the rehabilitation of prostitutes. It was not only Gladstone’s manner, Victoria believed his policies were damaging to Britain. After the massacre of the British mission in Afghanistan was avenged by the capture of Kandahar, Gladstone gave it back. In Cape Colony in southern Africa, the Boers (Dutch for ‘farmers’) crossed the Vaal River and proclaimed the Republic of Transvaal, later adding the Orange Free-State (north of the Orange River; named after the House of Orange). Gladstone abandoned Britain’s claims to the territory, a decision that Victoria opposed not just because it diminished the Empire, but because she believed that the Boers would mistreat the native Africans.

There was a crisis when General Gordon was besieged in Khartoum. Despite Victoria’s urging, Gladstone delayed sending reinforcements. When he finally did so, they arrived two days too late; Gordon had been killed, his head paraded along the streets on a pike. Victoria and the British public blamed Gladstone, and he was forced from power. He was soon back, and this time it was his programme of home rule for Ireland that enraged Victoria. She could not abide rewarding agitators, she saw it as the first step in the destruction of the Empire.

After Gladstone left office for the last time, Victoria’s relationships with his successors, Lord Rosebery and Lord Salisbury, were much easier; but it would never be as it was with Melbourne and Disraeli.

There was a problem when it was time for the last child to leave home. Princess Beatrice decided to marry Prince Henry of Battenberg, and Victoria showed her displeasure by not speaking to her daughter for seven months, communicating with her by written messages. In the end, Victoria gave her consent to the marriage, but only on condition that Beatrice and her husband agreed to live with Victoria.

Queen Victoria was now an institution, cheered by her people wherever she went. Her Golden Jubilee in 1887 drew enormous crowds, with more than 50 kings and princes attending, as well as numerous queens and princesses.

The celebrations were unaffected by newspapers revealing details of the ‘Jubilee Plot’. It was claimed that a plot by Irish nationalists to blow up Westminster Abbey, killing the Queen and her ministers, had been discovered. Two Irishmen, Callan and Hankins, were charged with bringing dynamite into the country. They were not charged with anything more serious because they had missed their ship in New York, and only arrived in Liverpool on the day of the Westminster Abbey celebration – too late to carry out their mission.

At their trial, it emerged that a man called Francis Millen had organised the proposed assassination. It seems that Millen was a British spy who had encouraged the plot in order to draw Irish nationalists into the conspiracy so that they could be identified and imprisoned. Also, it was hoped to discredit the Home Rule movement. Callan and Hankins were sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment; Millen was allowed to escape to America. Presumably the bombing would not have been allowed to take place.

Ten years later it was the Diamond Jubilee, and the celebrations were repeated.

Although Britain had annexed the Boer South African Republic in 1877, the Boers regained their independence after the First Boer War in 1881. The discovery by the Boers of massive gold reserves changed everything. Thousands of men rushed from Britain’s Cape Colony to find work and fortune in the gold mining areas, so much so that they soon outnumbered male Boers by two to one. To preserve their control, the Boers limited the political and economic rights of the

uitlanders

(foreigners). Britain demanded that they be given full rights; the Boers refused. Really, the issue was the new wealth of the Boer territories that threatened to overwhelm Cape Colony and also challenged London’s position as the world gold trade centre. War looked inevitable, and the Boers launched a preemptive attack in 1899, starting the Second Boer War.

It was now that Victoria became increasingly frail, and in early 1901 it was clear that the end was approaching. The Queen’s surviving children and grandchildren rushed to her bedside. On 22nd January, at 12.15pm, she stretched her arms forward and called out “Bertie!”. It was her last word. At 6.30pm, aged 81, she died and was taken to lie beside Albert in the mausoleum at Frogmore House near Windsor. Once more with Albert, in accordance with her instructions she was dressed in white.

It had been, and still is, the longest female reign in history, the longest reign by any British monarch. She was also the oldest British monarch, having beaten George III by four days, although she was overtaken by Queen Elizabeth II in 2007.

Victoria’s family had extended across Europe. It would not stop them going to war against each other – far from it – but it was the most amazing set of royal connections in history; so many kings and queens in the same family. Nine children, forty-two grandchildren and eighty-five great-grandchildren. In fact, the first grandchild to die was Sigismund, who died in 1866; the last to die was Princess Alice, who died in 1981 – the same generation, but separated by 115 years.

There can have been few, if any, monarchs in the history of the world who had been the victim of so many assassination attempts. And they all failed.

Sophie Antoinette Juliane Duke Ernest Ferdinand Viktoria Mariane Leopold Franz of Saxe(2) married (1)

Coburg and Gotha Duke of Kent Prince Emich Duke Ernest II

of Saxe–Coburg and Gotha

Albert ====== VICTORIA Carl Feodora

Victoria

EDWARD VII Alice Alfred Helena Louise Arthur Leopold

1840-1901 married

Emperor

Frederick III of

Germany

1841-1910 married

Alexandra of

Denmark 1843-78 1844-1900 1846-1923 1848-1939 1850-1942 1853-84

married Duke of married married Duke Edinburgh* Prince Duke of

Louis IV married

of Marie

Christian Argyll of

Duke of Duke of

Connaught Albany married Louise married Helena

Beatrice 1858-96 married

Prince

Henry

of

Battenberg

Kaiser

William II of Germany

+

Albert Victor

+ + + + + + +

Charlotte

GEORGE V Elisabeth Marie Albert Queen

of Romania

Arthur Charles

Victoria Eugenie (Ena) Queen of Spain

Henry Louise Irene Victoria Helena Patricia Leopold

+ + + + + +

Sigismund Victoria Ernest Alexandra Marie Maurice

+ + + + +

Viktoria Maud Freidrich Beatrice Harold Queen of Norway

+ + +

Waldemar Alexander Alix

Empress of Russia

+ +

Sophie Queen of Greece

Margaret

* later Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha