Arrest-Proof Yourself (11 page)

Read Arrest-Proof Yourself Online

Authors: Dale C. Carson,Wes Denham

Tags: #Political Freedom & Security, #Law Enforcement, #General, #Arrest, #Political Science, #Self-Help, #Law, #Practical Guides, #Detention of persons

SO WHO’S IN CHARGE? NOBODY!

The horror of the electronic plantation is that nobody’s in charge. Local judges can’t do anything because they have no jurisdiction beyond the state line and none whatsoever over the federal government, which maintains the NCIC arrest database. The U.S. Congress, which does have jurisdiction, gives privacy issues more hot air than action. Europe strictly guards data privacy; the United States does not.

Here’s another problem. Most lawyers and judges who work in the state criminal justice systems are paper people (in the federal court system, documents are filed electronically). For good and necessary reasons (anyone can say they didn’t get a fax or e-mail) judges and court officers do not send documents electronically, but have them served by certified mail or by human process servers. This is the only method so far devised that ensures that people actually receive summonses, complaints, subpoenas, court orders, etc. Most lawyers and judges view computers as glorified typewriters to be pounded by underlings. They are amazingly uninformed about the problems caused by electronic records releases and their use in discriminating against people with arrests but no convictions—and this includes records of false arrests and bad arrests.

Here’s something else you need to know that should raise goose bumps of fear. Felony arrests, in many states, can be based solely on the testimony of a credible witness. You say, so what? What’s so bad about that?

Imagine one day that your next-door neighbor or your ex-girlfriend or your ex-wife or your ex-boyfriend or your ex-husband who hates your guts calls the cops. He or she says, “Officer, that man threatened me. He beat me and said he was going to shoot me!

Help!

”

You’re innocent. You don’t like this person, and may have had some sharp words with him or her, but you never touched the person and never made a threat of bodily harm. Nonetheless, you can get arrested, fingerprinted, and dumped into the electronic plantation for life while the cops investigate what’s going on. Police are aware that people will lie and make false accusations in order to get their enemies arrested, but cops often err on the side of caution and arrest the person named anyway.

This actually happened to my coauthor. A guy who hates him wrote an anonymous letter to the sheriff’s office accusing him of various nefarious deeds. The cops were all over him for

two entire weeks

. Fortunately, as his attorney, I did the talking to the cops, so he was able to avoid interrogation and arrest. As for the poison dwarf who wrote the “anonymous” letter, we sued him.

There’s another demon at work here—bureaucratic convenience. Government agencies hate to hire clerks and dedicate office space to fulfilling document requests. They

really

hate records requests from the media, which can give any agency and administrator instant media burn for screwups. And they

really, really

hate records requests accompanied by Freedom of Information Act and Sunshine Law litigation (with attendant media scorching of all and sundry).

The bureaucratic solution? The light bulb that goes off in every administrator’s head?

Dump the whole thing onto the Web!

That’s right, put those expensive computer geeks to work. Digitize everything in every file folder. Then dump the whole shebang, now neatly organized into relational databases, into the black hole that is the Internet. This allows schools, colleges, cops, and private and public sector employers to check up on you 24/7 with a click of the computer mouse. It also allows government employees to do what they do best—get the heck out of the office by 4:59 P.M. as God intended.

But let us not unduly excoriate our bureaucratic friends. They get no direction from elected officials who, even if they are aware of the problem, couldn’t care less. People who have been arrested but not prosecuted or convicted are not a constituency anyone cares about.

CAN I HAVE YOUR SOCIAL?

Who has not heard a chirpy feminine voice on the phone or over the counter asking for your social security number? Hospital patients might as well have the number tattooed on their heads, since they get asked for it a dozen times a day. Pending perfection of universally accessible fingerprint and DNA identification systems, the social security number has become the de facto universal ID. With this magic number anyone can access an astonishing amount of information about you. The use of this number has created a multi-billion-dollar criminal enterprise called identity theft.

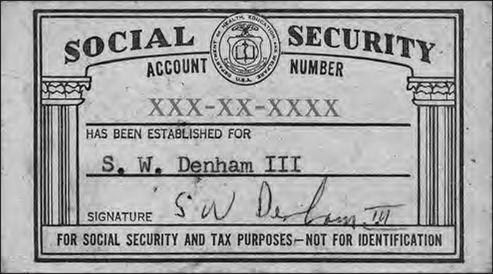

It wasn’t supposed to be this way. Look at the illustration of my coauthor’s social security card (the number has been omitted to keep him out of any more trouble than he’s already in). Can you read that last line, printed in uppercase by the government of the United States of America? It says, “NOT FOR IDENTIFICATION.” This card was issued in the 1960s. Ah, those were innocent years!

WHAT ABOUT MY RIGHT TO PRIVACY?

The short answer is you don’t have a

right

to privacy. You have some federal court opinions that assert that the nation’s founders kinda, sorta

intended

that you should have a right of privacy. Alas, these worthy 18th-century gentlemen forgot to actually write anything on the subject in the Constitution and Bill of Rights. Congress and state legislatures are all in favor of rights of privacy, but somehow they keep forgetting to pass bills into law.

Even if privacy laws restricting arrest records get passed, they mean nothing unless enforced. Heck, the right to vote regardless of race, creed, or color is quite clearly written in the Constitution, but until I was a teenager in the 1960s, Southern governors and legislators had difficulty understanding the concept. The sudden appearance of thousands of federal employees with uniforms, helmets, and guns brought about a rapid increase in the understanding of standard English among the Southern lawmaking elite. Here’s the bottom line: until privacy rights are enacted into law, and the law is elaborated into rules of criminal and civil procedure, and these laws and rules are upheld by judges and enforced by government employees wearing guns, you don’t have privacy rights.

THE RIGHT TO BE LEFT ALONE

3

As legislatures and Congress force themselves to contemplate privacy rights, I’d like to respectfully suggest they consider another right—to be left alone. The major problem addressed by this book is this: arrest is tantamount to conviction. It doesn’t matter that, after you were arrested, your case was “nol prossed” (

nolle prosequi

, Latin for “not prosecuted”) or that you were acquitted. Outside the criminal justice system, few people pay attention to such distinctions. Even if you were acquitted, people figure you were

arrested

, weren’t you? You must have been doing

something

. In the computer age, that arrest will follow you forever, and become, in essence, a lifetime sentence of shame, lost opportunities, and underemployment.

There are two antithetical trends occurring in this country. The first is the encouragement of diversity. We should understand people of different skin colors, religions, sexual orientations, and social circumstances. We should be less judgmental and cut our fellow beings a little slack. Perhaps we should even decriminalize drug use and think of this as a lifestyle choice, etc.

The second trend, far less discussed, is the enforcement of conformity. Any divergence from a narrow range of behavior is now punished by lifetime incarceration on the social services plantation and the electronic plantation. Arrests, traffic violations, debt payments, notes taken by schoolteachers and counselors and employers, and even malicious gossip contained in law enforcement interviews is subject to being indelibly recorded on computer databases and accessed by way too many people.

These two trends, of diversity and conformity, are antithetical. Advances in surveillance and data transmission make the power to enforce conformity overwhelming, even if its dispersed nature makes it less talked about and more difficult to understand. In an age in which your whereabouts are continuously recordable from GPS chips in your car and cell phone (or, if you are in custody, from your ankle bracelet) and your comings and goings at home and work are recorded by neighborhood and employment security systems that note each time you open gates and doors, privacy is a fiction. Ex-spouses, prospective employers, litigants, personal enemies, and even blackmailers can access this information at any time, sometimes with a subpoena, often without.

In a world where nothing is ever forgotten, nothing is ever forgiven. There is no wiggle room for minor indiscretions. Having a run-in with the cops, getting a traffic ticket, being somewhere you’re not supposed to be—these should not carry the life sentence of a permanent record. Once you’re on the electronic plantation, every cop, every government employee, every human resources weenie, every wireless phone company, and every geek with a credit card and Internet access is your judge and critic. As for ex-wives? Let’s not even go there! Who can stand such scrutiny? In the Bible the Lord declares, “Judgment is mine.” He has a point.

The protection of privacy is advanced in Europe (where even release of employee work telephone extensions is a crime) but practically ignored here. “Privacy issues,” alas, are discussed in this country by academic types in the plummy tones of National Public Radio. The issue is an eye glazer. I’m an old cop and not an abstract thinker, so I’m going to stick to the nitty-gritty and propose what I call Dale’s Bill of Rights in language everybody understands.

DALE’S BILL OF RIGHTS

1. To have records of arrests not leading to convictions made permanently unavailable to anyone, including judges before sentencing, except law enforcement agencies. Let’s make “innocent until proven guilty” actually mean something.

2. To have records of GPS tracking devices, gate security systems, computer monitoring software, and employment telephone recordings made permanently unavailable to anyone except law enforcement agencies. Where you go, who you call, and what you do are your business.

3. To have any and all psychological tests, assessments, job interviews, school interviews, and admissions documents made permanently unavailable to anyone—period. Dissemination of this stuff just speeds your check-in to the social service plantation.

4. To be free from involuntary counseling, psychoanalysis, personality profiling, and use of mind-altering pharmaceuticals. So what if you’re a little weird? Stay free.

5. To be left alone. To not have government employees, ex-spouses, enemies, and Nosy Parkers able to know everything you do, day in and day out, world without end, amen. It’s your life. Maybe it’s glorious, maybe it’s grubby, but it’s yours and no one else’s, at least not without a court order!

Well and good, you say, but these plantation horrors could never happen to me. Think not? To illustrate how these situations can become real, read Scenario #1 on the next page. This fictional account illustrates how incarceration on the electronic plantation could happen not to a ghetto kid, barrio thug, or trailer trash redneck, but to a nice, hardworking, ordinary guy.

SCENARIO #1

SEÑOR CRANE GOES INSANE

Our hero is a 35-year-old construction crane operator who, thanks to an ability to swim long distances under water, ran into the surf in Santiago de Cuba and swam under a barrage of machine gun bullets from Cuba’s Guardia de la Costa. He arrived freezing but unharmed in the Guantánamo Naval Base, considered U.S. territory. Thanks to special immigration laws, he quickly became an American citizen and moved to a large southern city.

Here he was happy for steady work with good pay as a construction crane operator. Every day it was up the high crane with a lunchbox and a jar to pee in, then eight hours lifting loads, then home. He was proud of his safety record of never having dropped a load or caused an injury. He had married a “real American,” blonde and blue eyed, and had helped put her through college and law school. She had made partner in a large law firm, and now they lived in a style that allowed him to drive a luxury car that astounded his truck-driving coworkers. He had twin daughters of whom he was foolishly fond.

At first his wife liked the fact that he was big, strong, Latin, and a real working guy, unlike her other boyfriends. After 10 years of marriage, however, her attitude changed. At the last Christmas office party, he had had, as usual, nothing to say to the suits who drank scotch, gossiped about judges, and speculated about who juiced who in the last election. They couldn’t understand his accent, and anyway they were uninterested in construction. His wife said that he had embarrassed her, that he was a nobody, and that he was hurting her career.