Armageddon (42 page)

“He [Hitler] was incapable of realising that he no longer commanded the army which he had had in 1939 or 1940,” said General Hasso von Manteuffel, the brilliant little forty-seven-year-old Prussian who had risen swiftly to command Fifth Panzer Army. Von Manteuffel was adored by his men, as a commander who always led from the front. Once, in a battle on the Eastern Front, a young tank officer heard a knock on his turret hatch, and thought it was Soviet shrapnel. Instead, it was von Manteuffel’s stick, as the general personally brought his tanks new orders. Now, von Manteuffel wrote of the chasm between Hitler’s ambition and his army’s capabilities: “It was not that his soldiers now lacked determination or drive; what they lacked were weapons and equipment of every sort.” Von Manteuffel also considered the German infantry ill trained. Lieutenant Rolf-Helmut Schröder, adjutant of the 18th Volksgrenadiers, agreed. He felt confident of the quality of his unit’s officers, but not of the men: “some were very inexperienced—and paid the price.” Schröder held the Waffen SS in high respect, yet he was irked by the manner in which they were always given the best available equipment, at the expense of the Wehrmacht. His own unit was issued with new assault rifles before the Ardennes, only to have them withdrawn a few days later, with the explanation that such weapons were solely for SS use.

Von Manteuffel and his fellow generals were disconcerted by Hitler’s appearance when they reported to him for a personal briefing at his headquarters near Ziegenburg in Hesse on 11 December: “a stooped figure with a pale and puffy face, hunched in his chair, his hands trembling, his left arm subject to a violent twitching which he did his best to conceal, a sick man apparently borne down by the burden of his responsibility. When he walked he dragged one leg behind him . . . he talked in a low and hesitant voice.”

Yet many rank-and-file German soldiers showed themselves more willing to believe in the Ardennes offensive than their commanders. Autumn Mist—the plan’s new codename—revived briefly, but in surprising measure, flagging hopes: “Our soldiers still believed, in the mass, in Adolf Hitler,” wrote von Manteuffel. “Somehow or other, they thought, he would once again turn the trick, either with the promised miracle weapons and the new U-boats or some other way. It was their job to gain him time.” Colonel Gerhard Lemcke, commanding the 89th Volksgrenadiers, said: “My comrades and I entered the battle with great confidence.”

The Allies’ failure to anticipate Hitler’s assault was the most notorious intelligence disaster of the war. It derived chiefly from over-confidence. For years, thanks to the fabulous Ultra decoding operation, German deployments and intentions had become known to the Combined Chiefs of Staff before orders had even reached German forward positions. American and British commanders had come to take for granted their extraordinary secret knowledge and even—in Montgomery’s case—sometimes to profess that this stemmed from personal insight, rather than from his privileged view of the enemy’s hand. Allied intelligence officers puzzled somewhat about the whereabouts of some German forces. An Allied summary of 13 December pondered “how long Sixth [SS] Panzer Army can remain isolated from the battle . . . There is much the enemy can gain by holding his hand with these formidable formations, and much to lose by committing them prematurely.”

But “orbat” intelligence about German unit deployments had diminished as the Germans withdrew across Europe, because they made more use of telephone landlines, impervious to interception. Moreover, Hitler imposed the strictest security on the build-up for Autumn Mist, including wireless silence. Allied air reconnaissance, anyway hampered by the winter weather, was unable to penetrate the great green canopy of the Ardennes forests, beneath which the panzers were gathering. German tank officers were ordered to adopt infantry uniform when reconnoitering the assault sector, though precious little prior inspection of the American lines was permitted at all. In a gesture reminiscent of Napoleon’s wars, the hooves of horses bringing guns forward were muffled with straw. Men were issued with charcoal for cooking, to prevent woodsmoke from betraying their presence.

The Allies’ most conspicuous error was to expect rational strategic behaviour from their enemy. There were clear pointers from intercepted communications, not least those of the Japanese ambassador in Berlin, that an offensive was brewing. There was much logistical evidence from Ultra of German accumulations of ammunition and fuel behind the quiet Ardennes sector, while these commodities were in desperately short supply in other, heavily engaged areas. Yet such pointers were ignored, because a German offensive seemed futile. Eisenhower, Bradley, Montgomery and their staffs made the same calculation as Germany’s generals. Yet during five years of war the Allies had been granted plentiful opportunities to recognize Hitler’s appetite for gigantic follies against the advice of his commanders. Five months earlier, the Anglo-Americans had profited from one of the greatest of these. The Führer had refused to allow a phased withdrawal in the west and insisted that Army Group B should fight in Normandy until it was largely destroyed. Yet in the winter of 1944 some Allied staff officers even suspected that his control of events was slipping. Hobart Gay, Patton’s Chief of Staff at Third Army, wrote in his diary on 16 November that he believed Hitler was no longer in charge of Germany.

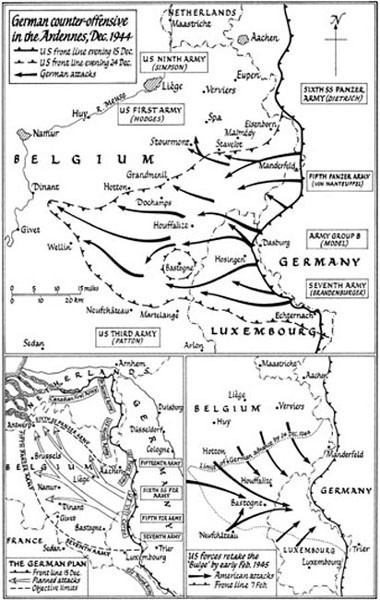

The outcome of all this wishful thinking at the highest level was that, when the Germans attacked on 16 December, the Allies were wholly unprepared. “Madness,” wrote Winston Churchill, “is . . . an affliction which in war carries with it the advantage of SURPRISE.” On the south of the front, the U.S. 6th Army Group had closed on the upper Rhine from Basle to the German border, save that the enemy still held out in the Colmar Pocket. Third Army had achieved some penetrations of the Siegfried Line, and was preparing a big new assault. First Army was close to the banks of the Roer, and preparing to attack its dams. Ninth Army and Montgomery’s 21st Army Group were still struggling in eastern Holland. SHAEF Intelligence estimated that the Germans possessed seventy-four nominal divisions in the west, equivalent to less than forty full-strength formations. The Allies mustered fifty-seven divisions.

The three German armies fell on the Americans some thirty miles south of the Roer sector upon which Bradley’s attention was focused. In the Ardennes three American infantry divisions—the 4th, 28th and 106th—were extended across a frontage of eighty miles, supported by the inexperienced 4th Armored. The 2nd and 99th Divisions faced the northern wing of the German assault. The 4th and 28th Infantry were weary and much depleted after their sorrows in the Hürtgen. The 106th was newly arrived and unpractised. The essential ingredients of a successful defence are obstacles covered by fire. Because the Americans were not expecting to be attacked, they had done little in the way of laying wire and minefields or digging deep bunkers. They occupied a few pillboxes inherited from the Germans, but had prepared no demolitions of bridges and culverts. The U.S. Army had traditionally paid little attention to defence, and in December 1944 saw little reason to do so. When American soldiers halted and entrenched, they did so only to pause between assaults. “Neither the 99th nor 106th divisions had dug in or made proper provision to meet an attack,” wrote Sergeant Forrest Pogue at V Corps after the battle began. “There is not the sort of all-night minelaying done by 2nd Division.” In some places, GIs even lacked good foxholes, because the frozen ground was impenetrable to entrenching tools, unless assisted by explosive charges.

Somewhat lackadaisical American patrolling, together with reports from local civilians, indicated heavy activity behind the German front, but this was not taken seriously. Noticing that most American units withdrew from outposts at night, the Germans exploited their absence. Even after the 106th Division heard tanks and vehicles moving on the night of 14 December, no one thought of investigating. The overriding enemy for every American soldier in Belgium and Luxembourg in the hours before the storm was not Germany, but the cold. It ate into men’s spirits as much as their bodies, seeped into every corner of foxholes and tents, ruined houses and vehicles, where fires flickered and sentries stamped their boots in the icy darkness. There was a very unAmerican shortage of antifreeze, which caused difficulties for soft-skinned vehicle drivers. Some men still lacked proper winter clothing. Many formations were suffering alarming casualties from trench foot. GIs explored desperate expedients. A buddy of Private Eugene Gagliardi in the 7th Armored Infantry Regiment tried to keep his hands warm with his Zippo lighter. “We couldn’t sleep, so we took our shoes off and took turns sticking our feet under the other guy’s armpit,” said Private First-Class Jack Pricket of the 393rd Infantry. Private “Red” Thompson desperately needed to wear his overcoat, but found that he could not run in it. He compromised by cutting off the bottom twelve inches of cloth, which cost him a reprimand from his disgusted platoon commander. A few hours later, officers had more urgent things to worry about.

On the evening of the 15th, the Germans who were to make the assault received a bottle of schnapps and a hot dinner apiece. There were peaches in rice for the engineers of 12th Volksgrenadier Division, “a feast for us,” in the words of Private Helmut Stiegeler. Then they began to advance in “goose march” formation—single file—in silence through the darkness. Light reflected off the snow enabled each man to see those in front of him quite clearly. There were spasmodic halts, as officers checked the route. “The villages through which we marched lay peaceful in the December night,” wrote Stiegeler. “Perhaps a dog barked here and there, or people were talking and looking at the passing soldiers. Out of an imperfectly blacked-out window a vague light shone out. With all these sights, most of our thoughts were of home in the warm houses with our families.” Suddenly, a glow spread across the night sky. The Germans had switched on searchlights, deployed skywards to guide the advance of 3rd Parachute Division, traversing paths cleared by the engineers. A short, sharp, furious German bombardment began to play upon the American positions. At 0530, the armour and infantry attacked.

As the first column of German tanks emerged from the trees near Losheim, the local American outpost commander called for artillery fire. Nothing happened. The defenders’ guns and mortars were, in many sectors, unready to fire effectively in front of their own positions. When the Germans closed in, they encountered pockets of brave and dogged resistance. But their spearheads were able to pierce the line in many places. There were far too few American soldiers to man a continuous line. On the 394th Infantry’s front, anti-tank guns had been positioned for a week, but their gunners had not bothered to emplace them. As German shells started falling, the crews fled into the infantry lines. Two anti-tank men tore the cover off a K Company foxhole, and were promptly shot by its occupants. Soldiers of the 394th’s B Company watched a German medical orderly work steadily at tending his unit’s wounded in front of their positions. He glanced up only once, to shake his fist at the Americans. Soon afterwards, the company’s survivors attached a white undershirt to a machine-gun cleaning rod and waved it aloft. Firing stopped, and they were herded to the rear as prisoners.

The 28th and 106th Divisions, in the centre of the front, held most of their positions on the first day largely because the Germans were content to bypass them and clear up later. The 28th Division, however, inflicted some sharp reverses on poor-quality German infantry formations. The attackers’ difficulties were increased by the fact that, in the interests of security, some units had been forbidden to carry out reconnaissance. “I never took part in an attack which was worse prepared,” said Colonel Wilhelm Osterhold of 12th Volksgrenadier Division. Some of his men cut the telephone wires to their own artillery, mistaking them for American booby-trap cables. This communications breakdown caused German shells to start falling among the Volksgrenadiers, inflicting serious casualties and stalling the regiment’s advance.

From the outset, there was a remarkable gulf between the performance of German armoured and infantry formations. The panzers, and especially the SS, attacked with their familiar energy and aggression. The infantry displayed a lack of enthusiasm, skill and training which shocked their own officers and contributed importantly to the German failure. This was emphatically not the Wehrmacht of 1940. Officers’ narratives resemble to a marked degree the tales of woe familiar in Allied accounts of offensive operations.

The forward American positions were bound to fall sooner or later, once the panzers had crashed through gaps in the line. A directive from Sixth SS Panzer Army emphasized the importance of such tactics, before the offensive began: “Watch for every opportunity to make flanking movements. Bypass enemy strongpoints and large towns.” This indeed the Germans did, seeping through the front wherever they encountered weakness, leaving isolated defenders to be mopped up by the following waves.

Private Donald Doubek’s platoon of the 106th Division had moved into the line on 15 December, with little idea where they were going or what they were supposed to do. They were ordered to dump their greatcoats and packs in a hamlet named Eigelscheid. Early next morning they found themselves being shelled and were ordered to fall back, which further confused and dismayed them. They took up defensive positions in the south-west corner of the village of Winterspelt, and lay awake all night listening to distant firing and watching flares go up. There were explosions nearby. Ray Ahrens, their scout, scuttled hastily through the door of a neighbouring house and found himself in a toilet. He stayed there for a while, feeling safer. The shelling became more intense next morning, 17 December. Their company commander was killed. His replacement told the men, “I’m going for help,” and disappeared, not to be seen again. Men began to slip away towards the rear, “not wounded, but dazed and wandering aimlessly.” At dawn Doubek’s platoon was sixteen strong. By the time the Germans took the survivors prisoner, there were only four of them. Doubek, hit in the hip by grenade fragments, found himself loaded into a captured Dodge weapons carrier, and driven away towards a PoW camp. His mother was handed a telegram reporting him “missing” just as she walked down the main street of El Dorado, Kansas, to buy stock for her little hat and dress shop. She collapsed and had to be taken to hospital.