Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble (35 page)

Read Ardennes 1944: Hitler's Last Gamble Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Kokott then improvised combat groups, taking command of four tanks which happened to be near by, an artillery detachment and some engineers, and reorganized some of the fleeing paratroopers who had recovered from ‘their initial shock’. He ordered them to move south to take up position blocking the roads. The situation soon appeared to be restored. The American armoured force in Chaumont had only been a reconnaissance probe by forward elements from Patton’s Third Army and, lacking sufficient strength, it pulled back.

The first warning the Germans received of the American airdrop to resupply the 101st Airborne and its attached units came soon after midday. The 26th Volksgrenadier-Division received the signal:

‘

Achtung!

Strong enemy formation flying in from west!’

The Germans sighted large aircraft flying at low level accompanied by fighters and fighter-bombers. They expected a massive carpet-bombing attack, and opened rapid fire with their 37mm anti-aircraft guns.

They do not seem to have noticed the first pair of C-47 transports which dropped two sticks of pathfinders at 09.55 that morning. On landing, the pathfinders had reported to McAuliffe’s command post in Bastogne to establish the best sites for the drop zones. Their mission had been deemed essential by IX Troop Carrier Command, because of fears that Bastogne might have already been overrun. The pathfinders then set up their homing beacons just outside the town and waited until the drone of approaching aircraft engines gradually built to a roar.

‘The first thing you saw coming towards Bastogne’

, recorded a radio operator in the first wave of C-47 transports, ‘was a large flat plain completely covered with snow, the whiteness broken only by trees and some roads and, off in the distance, the town itself. Next, your eye caught the pattern of tank tracks across the snow. We came down lower and lower, finally to about 500 feet off the ground, our drop height.’ As the parachutes blossomed open, soldiers emerged from their foxholes and armoured vehicles,

‘cheering them wildly as if at a Super Bowl or World Series game’

, as one put it. Air crew suddenly saw the empty, snowbound

landscape come alive as soldiers rushed out to drag the ‘parapacks’ to safety.

‘Watching those bundles

of supplies and ammunition drop was a sight to behold,’ another soldier recounted. ‘As we retrieved the bundles, first we cut up the bags to wrap around our feet, then took the supplies to their proper area.’ The silk parachutes were grabbed as sleeping bags.

Altogether the 241 planes from IX Troop Carrier Command, coming in wave after wave, dropped 334 tons of ammunition, fuel, rations and medical supplies, including blood,

‘but the bottles broke

on landing or were destroyed when a German shell blew up the room where they were stored’. Nine aircraft missed the drop zone or had to turn back. Seven were brought down by anti-aircraft fire. Some air crew were captured, some escaped into the forest and were picked up over the following days, and a handful made it to American lines.

‘Not a single German aircraft could be seen in the skies!’

Kokott complained. Luftwaffe fighters did attempt to attack the supply drop, but they were vastly outnumbered by the escorts and were chased away, with several shot down.

As soon as the transport planes departed, the eighty-two Thunderbolts in their escort turned their attention to ground targets. They followed tank tracks to where the Germans had attempted to conceal their panzers, and attacked artillery gunlines. Despite the best efforts of the air controllers, the Thunderbolts made several attacks on American positions. In one case a P-47 began to strafe and bomb an American artillery battery. A machine-gunner fired back, and soon several aircraft joined in the attack. Only when an officer ran out waving an identification panel did the pilots understand their mistake and fly off.

The attack of the 901st Panzergrenadiers against Marvie went ahead after dusk following the departure of the fighter-bombers. Artillery fire intensified, then Nebelwerfer batteries fired their multi-barrelled rocket launchers, with their terrifying scream. The German infantry advanced behind groups of four or five panzers. The 327th Glider Infantry and the 326th Airborne Engineer Battalion fired illuminating flares into the sky. Their light revealed Panther tanks, already painted white, and the panzergrenadiers in their snowsuits. The defenders immediately opened fire with rifles and machine guns. Bazooka teams managed to disable a few of the tanks, usually by hitting the tracks or a sprocket, which brought them to a halt but did not stop them from using their main armament or machine guns.

A breakthrough along the road to Bastogne was only just halted after McAuliffe threw in his last reserves and ordered the artillery to keep firing, even though their stocks of shells were perilously low. In fact the defenders fought back so effectively that they inflicted grievous losses. Kokott eventually abandoned the action. He then received an order from Manteuffel’s headquarters that he was to mount a major attack on Bastogne on Christmas Day. The 15th Panzergrenadier-Division would arrive in time, and come under his command. Kokott might have been sceptical of his chances, but the defenders were just as hard pushed, especially on the western side.

The Americans could not cover the perimeter frontage in any strength, and they sorely lacked reserves in the event of a breakthrough. With the front-line foxholes so spread out in places, paratroopers resorted to their own form of booby-traps. Fragmentation grenades or 60mm mortar shells were attached to trees with trip wires extending in different directions. Fixed charges of explosive taped to trunks could be detonated by pullwires running back to individual emplacements.

Just south of Foy, part of the 506th Parachute Infantry continued to hold the edge of the woods. Their observation post was in a house, outside which a dead German lay frozen stiff with one arm extended.

‘From then on,’

a sergeant remembered, ‘it was a ritual to shake hands with him every time we came or left the house. We figured that if we could shake his hand, we were a helluva lot better off than he was.’ Even with the sacks and bags from the airdrop, frostbite and trench foot affected nearly all soldiers. And Louis Simpson with the 327th Glider Infantry observed,

‘in this cold the life in the wounded is likely to go out like a match’

.

Facing the attack around Flamierge, Simpson wrote:

‘I peer down the slope

, trying to see and still keep my head down. Bullets are whining over. To my right, rifles are going off. They must see more than I do. The snow seems to have come alive and to be moving, detaching itself from the trees at the foot of the slope. The movement increases. And now it is a line of men, most of them covered in white – white cloaks and hoods. Here and there men stand out in the gray-green German overcoats. They walk, run and flop down on the snow. They rise and come towards us again.’

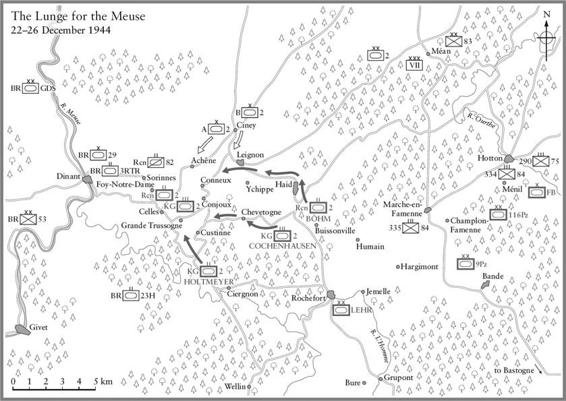

Bastogne had naturally been a priority for American air support, and so were the hard-pressed 82nd Airborne and the 30th Division on the northern flank. But the top priority that day, with half of all Allied fighter-bomber units allocated, had been to stop the German panzer divisions from reaching the Meuse.

From the moment the weather improved and the Allied air forces were out in strength, incidents of friendly fire, both from the air and from the ground, increased dramatically. Anti-aircraft gunners and almost anyone with a machine gun seemed almost physically incapable of stopping themselves from shooting at any aircraft.

‘Rules for Firing’

and instructions on ‘Air-Ground Recognition’ were forgotten. Soldiers had to be reminded that they were not to fire back at Allied aircraft who might be shooting them up by mistake. All they could do was to keep throwing out yellow or orange smoke grenades to make them stop, or firing an Amber Star parachute flare. The self-control of the 30th Infantry Division was the most sorely taxed. These soldiers had suffered attacks by their own aircraft in Normandy, and now in the Ardennes they were to suffer even more.

Bolling’s 84th Infantry Division and parts of the 3rd Armored Division continued, with great difficulty, to hold a line south of the Hotton–Marche road against both the 116th Panzer-Division and the 2nd SS

Das Reich

. Combat Command A of the 3rd Armored was pushed further round to the west, as a screen for the assembly of Collins’s VII Corps. The 2nd Armored Division, Patton’s former command known as ‘Hell on Wheels’, was arriving by forced march in great secrecy for a counter-attack planned for 24 December. The advance of the 2nd Panzer-Division was faster than expected. But Collins had been greatly relieved to hear from Montgomery,

‘chipper and confident as usual’

, that the bridges over the Meuse at Namur, Dinant and Givet were now securely defended by the British 29th Armoured Brigade. It was that night that the 8th Rifle Brigade killed two Skorzeny commandos in a Jeep. The main problem at the bridges was the flood of refugees fleeing across the Meuse to escape.

‘The German push has unsettled the whole population,’

wrote an officer with civil affairs, ‘and they seem to fear the worst. Already the refugees are moving along the roads and we are out to stop them causing trouble to traffic.’ Blocked at the bridges, Belgians resorted to boats to cross the Meuse.

Montgomery also assured Collins that the brigade would advance to link up with Collins’s right flank on the next day, 23 December, but A Squadron of the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment commanded by Major Watts was already at Sorinnes, six kilometres east of Dinant. Watts had no idea where either the Americans or the Germans were, so he spread his eighteen tanks out to cover every route into Dinant, using them more like an armoured reconnaissance regiment. For the three armoured regiments in the brigade, the great frustration was to be going into battle with their

‘battle-weary Shermans’

, rather than their new Comet tanks.

The British also started to receive valuable help from locals. The Baron Jacques de Villenfagne, who lived in the chateau at Sorinnes, just three kilometres north of Foy-Notre-Dame (not to be confused with the Foy near Bastogne), was a captain in the Chasseurs Ardennais and leader of the Resistance in the area. He acted as a scout for Watts’s squadron on his motorcycle, and reported on the advance of the 2nd Panzer-Division in their direction.

The approaching battle made one thing very clear to farming folk. They needed to prepare food for what could be a long siege, sheltering in their cellars. At Sanzinnes, just south of Celles, Camille Daubois, hearing of the advance of German forces, decided it was time to slaughter his prize pig, a beast of 300 kilos. Because it was so large, he felt he could not do it himself, and called the butcher, who was about to take refuge beyond the Meuse. He only agreed to help with the slaughter, but when he arrived and saw the animal, he exclaimed:

‘That’s not a pig, that beast’s a cow!’

Not prepared to use the knife he insisted on an axe, with which he severed the head. They strung it up to drain the blood and the butcher dashed off. But when men from a Kampfgruppe

of the 2nd Panzer arrived later, the pig’s carcass disappeared, no doubt to their field kitchen known as a

Gulaschkanone

.

Oberst Meinrad von Lauchert, the commander of the 2nd Panzer-Division, split his force just north of Buissonville to search out the quickest route to the Meuse. The armoured reconnaissance battalion, under Major von Böhm, moved on ahead towards Haid and Leignon because it had been refuelled first. Two panzers in the lead sighted an American armoured car and opened fire. The armoured car was hit, but the crew escaped. Its commander Lieutenant Everett C. Jones got word

to Major General Ernest Harmon, the commander of the 2nd Armored Division. The pugnacious Harmon, who was itching to go into the attack, ordered his Combat Command A under Brigadier General John H. Collier to advance immediately.

That evening the main panzer column, commanded by Major Ernst von Cochenhausen, reached the village of Chevetogne, a dozen kilometres north-west of Rochefort. The inhabitants of the village had so far had little more to fear than the V-1s flying overhead towards Antwerp, one of which had exploded in the woods near by. Apart from that, the war seemed to have passed them by. They had seen no American troops since the liberation of the area in September, and never imagined that the Germans would return.

Woken soon after midnight by the vibrations caused by tanks rumbling up the main street, the villagers crept to the windows of their houses to see if this force was American or German, but the vehicles were moving without lights and it was too dark to distinguish. The column came to a halt a little way up the hill, and then, to their alarm, they heard orders barked unmistakably in German. News of the massacres of civilians further east by the Kampfgruppe Peiper had spread rapidly. The black panzer uniforms with the death’s-head badge prompted many to believe that these troops were also SS. But the 2nd Panzer-Division was different, and its behaviour towards civilians was on the whole correct. On entering a farm kitchen in Chapois, one of its officers warned the surprised housewife that she had better hide her hams. His soldiers were famished and they would not hesitate to take them.