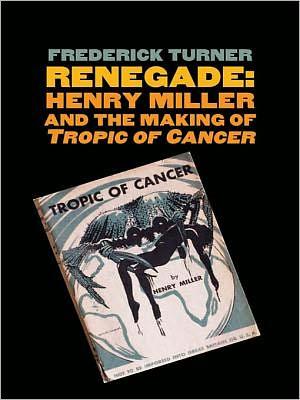

Renegade: Henry Miller and the Making of "Tropic of Cancer"

Read Renegade: Henry Miller and the Making of "Tropic of Cancer" Online

Authors: Frederick Turner

Tags: #Genre.Biographies and Autobiographies, #Author; Editor; Journalist; Publisher

Renegade

Henry Miller

and the Making of

Tropic of Cancer

Frederick Turner

Yale

UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW HAVEN & LONDON

Copyright © 2011 by Frederick Turner.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Turner, Frederick W., 1937-

Renegade : Henry Miller and the making of

Tropic of Cancer

/

Frederick Turner.

p. cm. — (Icons of America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-14949-4 (hardback)

1. Miller, Henry, 1891-1980.—Criticism and interpretation.

2. Miller, Henry, 1891-1980. Tropic of cancer. 3. Politics and

literature—United States—History—20th century. 4. Authors

and publishers—United States—History—20th century.

5. Publishers and publishing—United States—History—20th

century. 6. Censorship—United States—History—20th

century. I. Title.

PS3525.I5454Z8557

2012

813’.52—dc22

2011019531

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO

Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 I

Icons of America

is a series of short works written by leading scholars, critics, and writers, each of whom tells a new and innovative story about American history and culture through the lens of a single iconic individual, event, object, or cultural phenomenon.

The Hollywood Sign: Fantasy and Reality of an American Icon

LEO BRAUDY

Joe DiMaggio: The Long Vigil

JEROME CHARYN

The Big House: Image and Reality of the American Prison

STEPHEN COX

Andy Warhol

ARTHUR C. DANTO

Our Hero: Superman on Earth

TOM DE HAVEN

Fred Astaire

JOSEPH EPSTEIN

Wall Street: America’s Dream Palace

STEVE FRASER

No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage’s

4’33”

KYLE GANN

Frankly, My Dear:

Gone with the Wind

Revisited

MOLLY HASKELL

Alger Hiss and the Battle for History

SUSAN JACOBY

Nearest Thing to Heaven: The Empire State Building and American Dreams

MARK KINGWELL

Unwarranted Influence: Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Military-Industrial Complex

JAMES LEDBETTER

The Liberty Bell

GARY NASH

The Hamburger: A History

JOSH OZERSKY

Gypsy: The Art of the Tease

RACHEL SHTEIR

King’s Dream

ERIC J. SUNDQUIST

Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson

GORE VIDAL

Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown

DAVID YAFFE

Small Wonder: The Little Red Schoolhouse in History and Memory

JONATHAN ZIMMERMAN

For

Jim Harrison

Contents

Beginning the Streets of Sorrow

“Fuck Everything!”

At the end of August 1931, Henry Miller posted a letter from Paris to his Brooklyn boyhood pal, Emil Schnellock. He wrote as if he were some explorer, poised to plunge alone and unarmed into a wilderness. “I start tomorrow on the Paris book: First person, uncensored, formless—fuck everything!” he exclaimed.

As a telegraphic précis of what would three years later become

Tropic of Cancer,

the concluding six words of this brag are an astonishingly accurate prediction of the book Miller had somehow discovered he must write. When it was published in Paris in September 1934 by a man who dealt in what today would be called “soft pornography,” it completely fulfilled the bravado of Miller’s proclamation,

especially in its sustained tone of savage abandon—“fuck everything!”

The expression is, of course, street-corner argot for the defiant impulse to hurl aside all considerations, conventions, and costs and to strike out recklessly into uncharted territory and there achieve personally unprecedented success—or a final failure. Defiant though it is, the impulse must ultimately come from a profound sense of failure, of having been balked and defeated at every turn so that at last there is nothing left to lose. The successful don’t have to say, “Fuck everything!” Failures might, and in that deadness of late August in Depression-era Paris Henry Miller definitely belonged in the latter category: he’d apparently lost everything, nationality, job, wife, even his language, which he couldn’t use in this foreign place.

On a more literal plane, the book Miller was about to embark on was one in which the narrator and his lawless companions do indeed try to “fuck everything,” even perhaps so unlikely a target as the one-legged hooker Miller mentions in telling detail as he used to pass her nightly stand in the Place de Clichy:

After midnight she stands there in her black rig rooted to the spot. Back of her is the little alleyway that blazes like an inferno. Passing her now with a light heart she reminds me somehow of a goose tied

to a stake, a goose with a diseased liver, so that the world may have its

paté de fois gras.

Must be strange taking that wooden stump to bed with you. One imagines all sorts of things—splinters, etc. However, each man to his taste.

It was passages like this in which a profoundly forbidden form of sex is described with a cruel humor that prompted American tourists in Paris to smuggle home copies of the banned book soon after Jack Kahane’s Obelisk Press published it. They kept on doing so until the war interrupted travel to the continent. At the war’s end Gls discovered the book, and then eventually the tourists returned to guiltily and gleefully carry it back to the States wrapped in shirts or shawls. By the 1950s

Tropic of Cancer

had acquired a folkloric status while its author wore with an increasing unease the shadowy reputation as a writer of truly “dirty books”—or, as he occasionally styled himself with some bitterness, a “gangster author.”

Something of this reputation clings to Miller still, like smoke, though he is long dead. And yet over the years since 1934, and particularly since Barney Rosset’s Grove Press triumphed over the censors and published an American edition of

Cancer

in 1961, a simultaneous process has been at work. In it Miller’s purely literary reputation has steadily risen so that now he is generally—if somewhat

grudgingly—acknowledged to be a major American writer, maybe even a great one. And

Tropic of Cancer,

his first published novel, has risen from smuggled dirty book to American classic, a work that belongs on a select shelf of works that best tell us who we are, for better or worse.

Emil Schnellock might well have been pardoned had he reacted to his friend’s proclamation with a heavy dollop of skepticism. They’d known each other since they attended P.S. 85 in Brooklyn’s Bushwick section some thirty years back, and for much of that time, it seemed, Miller had been jawing about becoming a writer. But after all the impassioned, profanity-spattered talk, some of it brilliant and colored with various violent prejudices; after his furious work on three extended pieces of fiction; after he’d left his first wife because a second one believed in his dream—after all this he had perilously little to show for it. The fictions remained unpublished and were perhaps unpublishable, and only a clutch of his shorter pieces had seen print in obscure places. Meanwhile, Schnellock, from a similar background and harboring his own artistic aspirations, had become a successful illustrator with a studio in Manhattan. What now could he have thought of his old friend, starving over there in Paris, except that once again Henry had failed? Maybe he also felt a little guilty, because it was he who had been partially responsible for

Miller’s last-ditch, desperate decision to ship out for Paris in the winter of 1930, hoping the fabled city would somehow crack open that volcano of creative energy he felt he had within him. For Schnellock had seen Paris and the continent’s other great cities and had for years been filling Miller with exquisitely detailed descriptions of those places and of that deep humus of art and culture so abundantly available there. Without quite meaning to he had encouraged in his friend a conviction amounting to a lifelong mania that America was hostile to artists, whereas the Old World was unfailingly nurturing. And when the desperate Miller, facing the death of his dream, and having really nowhere else to go, had decided it had to be Paris or bust, it had been Schnellock that he turned to, not his second wife June, who couldn’t wait to be rid of him. Schnellock had put some steel in his spine and ten dollars in his pocket for the trip across the dark Atlantic and then down at the docks had seen him off.

Besides his ticket and Schnellock’s tenner, Miller shipped with two valises and a trunk. In these he had some suits made by his tailor father, the drafts of two of the failed novels, and a copy of Walt Whitman’s

Leaves of Grass.

But within him, buried beneath the accumulated detritus of a random and crudely assembled self-education, Miller was carrying a great deal more than these meager effects. In the lengthening years of his exile it became evident to

him that his task was to discover through deprivation and doubt and often intense loneliness what this was that he carried and to learn how to make creative use of it.

From young manhood he had hated what his native land had become: more mercenary than the meanest whore and viciously intolerant of real or suspected deviations from the national norm. Such a phase in intellectual development, of course, is hardly unusual in young people in America and elsewhere in the developed world. But in Miller’s case what he came to believe at so early an age he still believed on the last day he drew breath. Perhaps somewhat inchoate in his schoolboy years, this habit of mind was well established by the time he joined the workforce out of high school. By the time he shipped for Paris it was a pillar of his personality, a way of explaining where he now found himself, and the longer he was away from America, the more he hated it until the hatred became a hysteria that spattered the pages of his interminable letters to Emil Schnellock. When the war exiled him once again—back to America—he found his old home as hateful as ever and poured his feelings about it into such books as

The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

and its sequel,

Remember to Remember,

which invidiously compares America to

la belle France.

But if in 1930 he had imagined that Paris (and more generally the Old World) offered an authentic

escape from the coarseness and heartlessness of America, he was wrong. Wrong about Henry Miller, anyway, because no one could have been in a certain sense more ineradicably American than the man who had left it on that wintry February morning. To be sure, he was definitely not a mainstream American, but still he belonged to a strong, colorful countervailing tradition of cranks, crooks, tall-talkers, hucksters, adventurers, outlaws, and utopian dreamers that had its roots deep in the American experience.