Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life (21 page)

Read Anne Morrow Lindbergh: Her Life Online

Authors: Susan Hertog

For the moment, Charles was content to remain on Long Island. Even though the Morrow family had gone to their end-of-summer retreat in Maine, Charles stayed an extra week to watch the air races in

Westhampton.

30

Relaxed and satisfied, Charles made a sudden truce with reporters, permitting them to take photographs and conduct interviews. Anne, meanwhile, was bursting with impatience to see her family. She missed her parents and her sisters. “I dream of North Haven every night,” Anne wrote to her mother.

31

The Odyssey

A

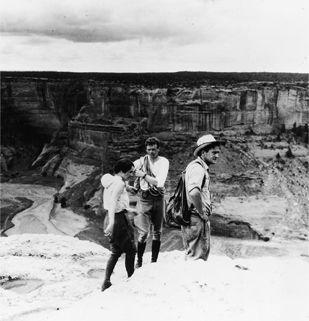

nne and Charles, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, 1929

.

(Lindbergh Picture Collection, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library)

And this should give you pause my son; don’t stay too long away from home, leaving your treasures there and brazen suitors near. They’ll squander all you have and take it from you, and then how will your journey serve?

—HOMER,

The Odyssey

EPTEMBER

11, 1929, N

ORTH

H

AVEN

, M

AINE

A

t last, Anne and Charles arrived!

Elisabeth shouted wildly to her mother as she watched their red sports plane

1

swoop down at sunset onto the meadow behind the house. Thrilled to see Anne safe on the ground, Betty rushed out the back door waving her arms in circles of joy.

Having been called on a search mission for a TAT airliner lost in the mesas of Arizona and New Mexico, they had arrived three weeks later than expected. It was not surprising, considering their eagerness to return home, that the Lindberghs set a new speed record on their flight from St. Louis: 905 miles in five hours and twenty-one minutes. Elisabeth remarked that Anne looked very tired, as though the trip had frayed her nerves.

But Anne was pleased to be “home” again. Even this remote eighty-four-acre estate on the northwest coast of a tiny island in Penobscot Bay was warm and inviting after four months of nomadic life. Set on a windswept point, surrounded by meadows and lawns, the house was a rambling New England farmstead with a touch of Colonial style. While it lacked the majesty of the Lamonts’ Sky Farm, it rivaled the neighboring summer estates inhabited since the turn of the century by Boston bankers and Wall Street financiers. Betty had commissioned Delano and Aldrich to build the house in 1928, at the same time she had authorized Next Day Hill, and she designed a separate cottage for her children, hoping to give them privacy and space.

2

Now, after many weeks of waiting, Anne and Charles were finally there.

They had missed the social highpoint of the summer: the Pulpit Harbor sailboat race, capped by a party on the Lamonts’ back lawn. And there was already a chill in the evening air and a tinge of crimson on the ridge of maples. But the days were still warm enough to sail and picnic, and to walk along the cliffs and wildflower meadows of the outlying islands. The next day Betty packed lunch, and they sailed southwest through the jagged maze of inlets and harbors to the White Islands. As Charles, Betty, and Dwight lingered behind, Anne and Con, in blue jeans and red scarves, leaped across the rocks with childlike abandon.

3

Three months apart had been painful to all of them; they were so pleased to be together again. But Dwight had serious matters on his mind. Since Anne’s marriage to Charles and the constant risk she took in flying, Dwight feared her premature death. He wanted to bequeath Anne some money, but he worried that it would pass out of the Morrow family if Anne and Charles were to die at the same time. Dwight talked to Anne and Charles about his making such a will, but Dwight and Charles disagreed about the terms. Finally, however, Dwight decided to leave $1 million in trust to Anne, money that would revert to the Morrow family on her death.

4

Because of the thick fog blanketing North Haven, Betty, Dwight, Anne, and Charles delayed their flight to Englewood. Elisabeth, however, left by boat for Boston. She wrote to Connie that a strange happiness had enveloped her those last few days. She felt certain she would never get married and vowed to find happiness by establishing her school.

5

She then set about surveying the grammar schools of Massachusetts, sending a running narrative to Connie as she did so. Anne and Charles, back in Englewood, prepared for a three-week air mail and survey tour. It was to be a 7000-mile flight, the longest since Charles’s 1928 good-will tour. Meticulously planned, minute by minute, the flight would circle the Caribbean through the islands to the northern coast of South

America and back through Central America to Cuba and Florida. The goal was to survey existing Pan Am routes from Miami to Paramaribo, Dutch Guyana, and to study the possibility of passenger travel across the Canal Zone.

6

Flying in a German-owned, state-of-the-art, Sikorsky twin-engine amphibian plane, the Lindberghs were to be accompanied by Juan Trippe, the president of Pan American Airlines, and his wife, Betty.

7

At dawn on September 18, Anne and Charles set off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, accompanied by a co-pilot and a radio operator, to meet the Trippes in Washington.

8

Unlike their previous survey flights alone in their private monoplane, this was a public relations event designed to convince sixteen governments, along with the American people, of the viability of commercial flight. An arduous, back-breaking tour, it was brilliantly staged by Trippe to have the look and feel of an upper-class excursion—socialites embarking on a leisurely cruise. Charles wore a gray business suit, his helmet discreetly held in his hand, and Anne wore a pastel chiffon dress and a brimmed straw hat. Trippe, who didn’t particularly like to fly, followed Lindbergh like his “shadow” in a white Panama suit and brown-and-white saddle shoes. Only his wife exuded ease, joking with reporters and charming the officials.

9

They rose each morning at four and were in the air by seven. When they stopped every few hours to refuel and to deliver and pick up mail, they were met by cheering, flag-waving crowds. And when they weren’t at receptions, dinners, or parties, Anne sat on the plane in a comfortable lounge chair, writing in her diary and reading books.

10

She may have appeared absurd to those around her, like a misplaced matron on her suburban front porch; in fact, she was examining the metaphysics of spatial and human relationships during flight. She concluded that distance was mental, not physical. The sound and touch of people back home were as vital as the quality of one’s imagination.

11

They toured the Caribbean islands, stopping in Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, and Trinidad. In lyrical images, Anne describes the magnificent beauty of the land and sea, never before viewed from the sky—the “rich

green” land, the “iridescent” seas,

12

and the majestic cliffs “plunging” into “turquoise” waters.

13

But as they flew across the constellation of islands, Anne worried that she and Charles were the harbingers of change that might destroy both the culture and the land. Progress, Anne realized, could be an illusion. She deplored the arrogance that led to the exploitation of people and land.

14

She marveled at Charles’s prediction that the islands would be only a day’s journey from the U.S. coastline, and wondered whether this access would breed the commercialism she had seen in Nassau.

As news of their flights rippled through the foreign press, the size of the crowds swelled to thousands. Symbols of “progress,” they were embraced—sometimes too heartily. When they arrived at the final mail-route stop in Paramaribo on September 23, government officials were determined to parade them through the streets, like icons of American technology, in a car hung with red, white, and blue lanterns. Charles declined, but was compelled by sheer courtesy to ride behind the official limousine in an unmarked car. The torches were lit, the band played “Lucky Lindy,” and people ran and shouted alongside their car. “Charles,” wrote Anne, “gritted his teeth and didn’t look to left or right—that look of contained bitterness … a wild mad dream.”

15

On October 10, on the way back to Florida through Central America, they made an unannounced detour from Belize across unexplored territory between Yucatán and the British Honduras. Unlike their jaunt the year before, this time they were accompanied by the Carnegie Institute archaeologist Alfred V. Kidder and by a coterie of reporters more interested in the drama inside the plane than in the Mayan ruins they had come to document. They reported that, even at ten thousand feet, Anne was the ideal hostess, serving a two-course meal during the flight, tidying up the cabin after the men, and intermittently acting as Charles’s navigator and photographer. The reporters were awed as much by her precision as by her grace.

16

While Anne and Charles were living like vagabond performers in a circus, the Morrows were trapped by illness and circumstance. Dwight

Jr. had been sent home from Amherst College, depressed, confused, and on the edge of a breakdown. Once again, Betty and Dwight struggled with their feelings as they prepared to send him to a sanitarium, this time in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. His physician, Dr. Austen Riggs,

17

said he was much improved; he could not, however, assure them that their son’s sweeping moods of depression and elation would not return.

As usual, Dwight tried to convince his son that health was an act of will. For the first time Betty wondered whether her son was overwhelmed by his father’s expectations, but her Puritan ethic prevailed. She decided he needed to stand straight and tall, meeting the challenge on its own terms. Only then could his ambitions be fulfilled. Resolved to help him, Betty hired a professional tutor.

18

Once Dwight Jr. was settled in Stockbridge, the Morrows prepared to return to Mexico. Anne and Charles were flying at record speed up the coast and around the gulf at the same time that the Morrows lumbered by Pullman train through the Midwest on their week-long journey south. They were welcomed in Mexico City by huge crowds, but nothing was quite the same. Mexico was no longer at the center of their lives. Betty missed Englewood and Anne, Dwight had his mind on New Jersey politics, and Elisabeth, now living in Mexico and ill with heart disease, was homesick even in the presence of her parents.

19

Anne, too, was lonely, and missing home, which had now assumed a new definition. It was not a place so much as an ideal, clothed in family relationships. When the Morrows were together, they were “home.” Formerly, they had moved as if in concentric circles, but Anne was about to find a new orbit on the outer rim. After nearly a week in Englewood Anne wrote to her mother in Mexico that she was expecting a baby. The news sent Betty Morrow into fits of anxiety.

Betty was consumed with thoughts of Anne, no matter where she went or what she did. Even a game of golf with Elisabeth couldn’t distract her. It was as if she could hear Anne’s loneliness through her words, and Betty longed to hold and comfort her as she had done in the days before her wedding.

20

When Anne and Charles had arrived in Englewood during the last week of October, the house was empty. Anne reveled in the comfort and familiarity; she rearranged the furniture in her room and rummaged through the closets and attics to find objects from her childhood. The thought of a baby of her own stirred the wish to hold on to the past, even though she couldn’t remember having been happier than in the present. Released for the moment from Charles’s schedule, for the first time since her marriage, Anne had time for herself. When Charles went off to Panama on business for Pan Am, Anne wrote sonnets,

21

read Chekhov and Tolstoy, and visited childhood friends.