0062104292 (8UP)

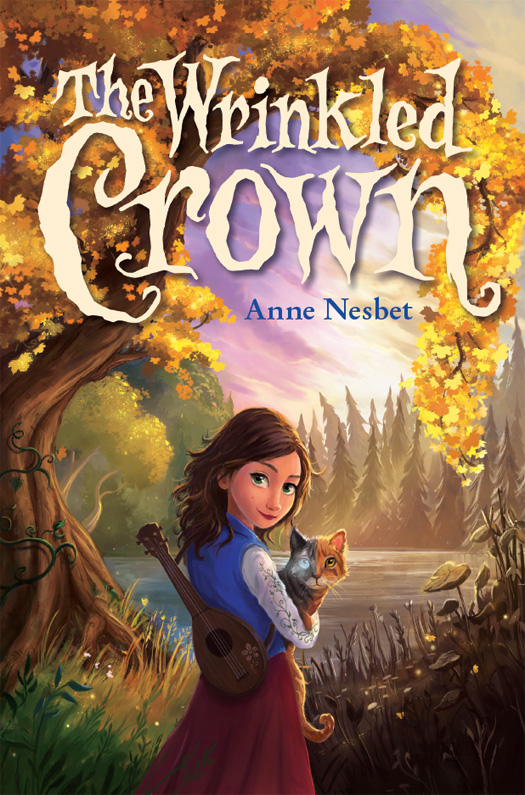

Authors: Anne Nesbet

For all those who would go down into the Plain

for a friend, and, in particular,

for Isa and Jayne.

CONTENTS

- Dedication

- 1. Never Touch a Lourka

- 2. Some Things Nobody Knew

- 3. What Doom Sounds Like

- 4. I Will find Her

- 5. That Lummox Elias

- 6. Twists in the Path

- 7. “Thank You, Brave Linnet!”

- 8. The Lay of the Land

- 9. A Door in the Wall

- 10. In the House of the Magician

- 11. Linnet Alone

- 12. The Price of a Fancy Breakfast

- 13. The Death and Dollop

- 14. Race to the River

- 15. The Bridge House

- 16. The First Surveyor

- 17. Strong Tea

- 18. Locks and Latches

- 19. Escaping into the Dark

- 20. Deeper and Darker

- 21. Doors and Keys

- 22. The Girl from Underground

- 23. The Thing about Crowns

- 24. Unwrinkled!

- 25. Disaster

- 26. Into the Plain

- 27. About Surveyors

- 28. The Plain Sea

- 29. Back to the Edge

- 30. To the Edge

- 31. Sayra

- 32. Complications

- 33. Ouch!

- 34. Home Again

- 35. Girl with Lourka

- Acknowledgments

- Back Ad

- About the Author

- Books by Anne Nesbet

- Credits

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

I

t was maybe Linny’s last day of all—a pretty horrible thought—but the air in the meadow was humming with sunlight, as if nothing were the slightest bit wrong. Green and warm, the smell, with a tang to it that was all from the sheep: three parts wool, one part manure. Or maybe it was better to say the whole meadow smelled just slightly of sheep’s cheese—sheep’s cheese and hay.

Hey!

Linny gave her head a shake to get rid of the webs cobbing there. This was no time to be thinking about sheep!

Tomorrow she would be twelve, no longer a child. Twelve was not any old ordinary birthday, not up in the wrinkled hills, not for a girl. It was a gate that didn’t let everyone through. Even Linny—who had once sucked actual real snake venom out of a friend’s arm and spat it boldly on the moss, where it sizzled like hot grease—even bold Linnet had to turn her mind away from the thought of the birthday coming for her, inching closer with every

tick rattle tick

of the village clock.

Tomorrow is not now. Tomorrow is very far away

.

And to rub it all in, the faint sweet strum of a lourka rose up from the village behind them, making Linny’s heart sore.

Round bellied, four stringed, golden voiced—there was nothing anywhere quite like a lourka from Lourka.

Whether the village was named after the instrument or the instrument after the village, nobody knew for sure. What mattered was this: if a girl so much as touched a lourka during her child days—even by accident! even tripping over her own papa’s instrument in the dark!—then on her twelfth birthday, the Voices would come, and off they would take her soul to Away.

“Oh, let’s go!” said Linny, tugging the cord that tethered her and Sayra together, the mismatched twins. “It’s late already, and there’s so much to do!”

No one knew where Away was, up past the most wrinkled parts of the highest hills, but it didn’t sound like a place you could sneak home from.

“You can’t get there from here, nor back again neither.”

That was what the miller liked to say about Away. And there had been a girl taken when he was a boy, so he must know.

It made Linny mad just thinking about it, so mad she kicked the ground—and Sayra stumbled. That’s the way

tethers are. Cause and effect, always causing trouble.

“No stomping!” said Sayra, but she laughed as she said it. “You’re the one with the birthday coming! You should be happy as a duckling.

Tomorrow

you get to throw this tether

right into the creek

, if you want to. Tomorrow you’ll be free.”

Being Sayra, she didn’t point out that she, Sayra, would also be free from that tether tomorrow. Maybe she didn’t even think that thought, she was so good (but Linny thought it for her). No, Sayra just picked up a couple of spilled needles and tucked them cheerfully away:

“And so I’d

think

you’d be starting to be happy already today, knowing it’s your birthday tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow!” said Linny. She was grumbling, she knew it, but she couldn’t help it. “

If

I’m still here.

If

the Voices don’t come and—”

“Don’t tell such stories!” said Sayra, and gave Linny’s hand a sharp tap for good measure. You had to be careful about the things you said, this high up in the wrinkled hills, where stories had a way of coming true. “Nothing’s going to happen to you. There’s been the tether protecting you in the village, and the woods keeping you safe out here. And tomorrow you won’t even have to worry anymore. A miracle, that’s what my mother says. A mi-ra-cle!”

It was a miracle because there hadn’t been a girl born

as hummy as Linny in a hundred years. Linnet’s father had even made a cage to clamp over the top of her cradle, though how could a cage do much to protect a child so hungry for music? Oh, but the whole village loved Linnet and had been willing to take desperate measures to keep her safe.

Which was why she was tethered to Sayra during most of every day.

No music fire in Sayra! Her talents were the safer ones of needle and cloth, and she had a quicksilver smile and green eyes and a face that could play tricks on you, shifting from sweetness to monster scowl in less than a blink. And back again. With eyes that sparked and laughed, sparked and laughed, the whole time.

Linny and Sayra knew each other far better than even the best of friends usually do, because Linny had been tethered to Sayra since she had learned to crawl.

“You are a good girl,” the grown-ups had said to Sayra then, who was only a toddler herself at the time. “You will not let your friend Linny get near a lourka. We have all promised to keep her safe.”

Sayra was a good girl, but she wasn’t

that

good, thank goodness. Here’s a secret: sometimes she let Linny run free in the woods, and both of them were happy, and nobody else could ever, ever know.

“Tomorrow you’ll be free like a rabbit! Wait . . . stand

still—you’ve got a thread loose there.”

Sayra hated loose threads.

“Free to hop around Lourka,” said Linny, making a face. While Sayra tied off that thread, Linny shuffled from foot to foot and thought grumbling thoughts about hopping around Lourka.

Lourka was a very small world, as far as Linny was concerned. The village; the meadows; the woods; the hills. And everyone knew that if you walked away too far downhill—if you went past the boundary trees or around one too many bends in the creek—you would never ever find your way back.

You were born in Lourka, or you had wandered there, but it was not a place you could return to by choice, once you had left. That was the story. Once in a blue moon a breathless stranger might wander in from elsewhere, as Linny’s own mother had long ago done, all footsore, hillsick, and amazed, but no one Linny had heard of had ever left, striding off past the boundary trees, and then actually returned.

“Don’t grumble,” said Sayra. “You’ll be free to hop anywhere you want, I guess. And to make music, too, once you’re officially twelve and it’s safe. That should make you happy! Not to mention—now I can give you your birthday present! Which I made myself, you know, so you’d better like it.”

Sayra could make anything (anything) with needle, thread, and a scrap of cloth.

“My birthday’s

tomorrow

, not today,” said Linny.

“I dreamed I shouldn’t wait. I dreamed I should give it to you today,” said Sayra, and she looked with her green eyes right at Linny, trying very hard to keep her gaze steady. But the blinking gave her away, and the wobble at the corner of her mouth. Linny felt the worry surge up in her again.

“Anyway,” said Sayra. “Tomorrow they’ll all be fussing over you, and I won’t get a word in edgewise.”

They were settled comfortably on the rocks they liked best, in a clearing nobody else ever came to, high in the Middle Woods. Sayra reached into her sewing bag and opened her hands so carefully that Linny thought the gift must be something living, a new-hatched chick or even a frog.

But no, it was a wonderfully wrinkled gift: a band of cloth, all embroidered with pictures of things they knew from their woods, and tucked into a little pocket in the middle, there was a bright bud of a flower, sewn from the prettiest scraps of satiny cloth. The best of all possible birthday sashes, with satin ribbons to keep it safely tied around Linny’s waist.

“Oh!” said Linny, delighted, as she was always delighted by the things Sayra’s thin, clever fingers made.

“It’s got the wolf and the snake!”

They had saved each other’s lives three times already. There was the sinewy blue wolf with huge teeth, way back when they were still very small, that Sayra had thrown pinecones at and somehow driven away (and the grown-ups had gone looking afterward and seen no trace of it, so Linny had been unfairly warned against telling stories, which is such a dangerous business up in the hills), and there was, of course, the snake that had casually sunk its fangs into Sayra’s arm. They never told anyone about that.

And right there on that embroidered sash was also the tree Linny had fallen out of, when she had climbed up to get a sense of the hills. Sayra had retethered her, picked her up, and carried her all the way down to the village, which goes to show how much stronger Sayra was than you might think, just by looking at her. And that had been the third time.

“Shh, silly, that’s not all,” said Sayra, narrowing her leaf-colored eyes. “Watch now. I put some of you and some of myself right into it, because it’s your birthday.”

The threads that ran through that rosebud must have been spun from wrinkled silk, magic in every fiber, because the bud was already blushing a deeper pink as Sayra held it on her palm. (Sayra’s mother had a glass-walled warm room where little silkworms spun their

amazing cocoons.) Oh! And now it began to open up, blossoming into a red rose flower. Linny clapped her hands in wonder, but Sayra put her finger to her lips: there was more. The rose darkened and purpled and changed, until it was a butterfly of silk, fluttering its pretty wings—and the wings of the butterfly had pictures sewn on them in threads of many colors, and those pictures shifted as Linny watched. She saw herself, Linny, running under the trees, and a tiny Sayra bent over her sewing while a few blue stitches flowed by, to make a thready creek, and there was Sayra’s house, and Linny’s, and even Linny’s young brothers, waving the tiniest of little silk hands. And then the butterfly curled up into itself and became a flower bud again, and Sayra tucked the bud into the pocket on the cloth band there, and folded that whole incredible silky present right into Linny’s amazed hand.

It was like a song, inside a story, made out of silk.

There was no one like Sayra.

Sayra gave Linny’s shoulders a hug.

“Want to spend the day quietly singing to me? Wouldn’t that be the safest safest thing to do? No, no, all right. Look at you twitching at the thought of it. Go run wild in the woods, then, like you always do. But don’t mess up!”

“Mmm,” said Linny, made frankly itchy by the worry that wouldn’t get out of her head.

“I’m serious: one more day! Don’t even go near the village where a lourka might grab you. Don’t get caught, and

don’t get lost

,” said Sayra.