Ancient Iraq (49 page)

The Parthian Period

The Parthians – a branch of the Scythians – appear for the first time in history

c

. 250

B.C

, when Arsaces led his nomadic tribesmen out of the steppes of Turkestan to settle in the north-eastern corner of Iran.

33

By 200

B.C.

, the ‘Arsacids’ were firmly established between the Caspian Gate (Hecatompylos) and the region of Meshed (Nisaia). Between 160 and 140

B.C.

Mithridates I conquered the Iranian plateau in its entirety and, reaching the Tigris, pitched his camp at Ctesiphon, opposite Seleucia. The Seleucid Demetrius II succeeded in recovering Babylonia and Media for a few years, but in 126

B.C.

Artabanus II reasserted his authority over these regions, and from then on the Tigris-Euphrates valley remained in Parthian hands – save for two brief periods of Roman occupation under Trajan and Septimus Severus – until it fell under Sassanian domination with the rest of the Parthian kingdom in

A.D.

227.

To govern their empire the Arsacids could only rely upon a small, if valorous, Parthian aristocracy, but they had the intelligence to utilize the social organizations created by the Seleucids, or those which had grown upon the ruins of the

Seleucid kingdom. They encouraged the development of Hellenistic cities and tolerated the formation of independent vassal kingdoms, such as Osrhoene (around Edessa-Urfa), Adiabene (corresponding to ancient Assyria) and Characene (near the Arabo-Persian Gulf).

31

Towards the beginning of the Christian era Hatra, an old caravan city on the Wadi Thartar, 58 kilometres west of Assur, acquired its autonomy and became the centre of a small but prosperous state known as Araba.

34

The Arsacids and their vassals were rich, since they controlled practically all the trade-routes between Asia and the Greco-Roman world, with the result that the second and first centuries

B.C.

were marked in Mesopotamia by intensive building activities resulting from governmental or regional initiative. Not only were Seleucia, Dura-Europus and, presumably, other prosperous market-places provided with a large number of new monuments, but towns and villages which had been lying in ruins for hundreds of years were reoccupied. In southern Iraq traces of Parthian occupation were found on almost every site excavated, in particular Babylon, Kish, Nippur, Uruk and even forgotten Girsu. In the north Assyria was literally resurrected: Nuzi, Kakzu, Shibanniba were inhabited again, and Assur, rebuilt anew, became at least as large a city as it had been in the heyday of the Assyrian empire.

35

But it must be emphasized that the revived settlements had very little in common with their Assyrian or Babylonian precursors. Several of them, if not all, had straight streets, often lined with columns, a citadel, usually built on top of the old ziqqurat, and an agora wherever possible. Walls of stone or ashlar-masonry replaced the traditional walls of mud bricks, while the buildings themselves, with their lofty vaulted chambers wide open on one side (

iwan

), their elegant peristyle and their decoration of moulded stucco, differed from the buildings erected by Mesopotamian architects as markedly as the Greco-Iranian statues of the rulers of Hatra differed from those of Gudea or Ashurnasirpal.

These archaeological data, combined with textual evidence, point to a massive influx of foreign population. The Greek and

Macedonian settlers, probably not very numerous at the beginning, had lived side by side with the Babylonians with relatively few social contacts; they had preserved their nationality, their institutions, their art, their language, their ‘Greekhood’ in a word, and were still keeping it under the protection of enlightened monarchs who called themselves ‘philhellen’. But the newcomers – mostly Aramaeans, Arabs and Iranians – settled in Mesopotamia in very large numbers, and mixed with the native population more easily since they were of Oriental, often Semitic stock and spoke the same language. Each city, old or new, gave shelter to several foreign gods. At Dura-Europus, for instance, were brought to light two Greek temples, an Aramaean sanctuary, a Christian chapel, a synagogue and a Mith-reum, let alone the shrines of local deities and of the gods of Palmyra. Similarly, the Sumero-Akkadian god Nergal, the Greek god Hermes, the Aramaean goddess Atar'at and the Arabian deities Allat and Shamiya had their temples in Hatra, around the majestic sanctuary of Shamash, the sun-god common to all Semites. Even at Uruk, the ancestral home of Anu and Ishtar, can still be seen a charming little temple, more Roman than Greek in style, dedicated to the Iranian god Gareus, and the remains of an extraordinary apsidal building believed to be a temple of Mithra.

36

Jews were numerous in Mesopotamia, and from about A.D. 30 to 60 or even more, a local family converted to Judaism ruled over Adiabene from its capital city Arbela (Erbil).

37

According to the Oriental tradition, during the same period Christianity began to penetrate into northern Mesopotamia coming from Antioch and Edessa.

This flood of people and ideas submerged what was left of the Sumero-Akkadian civilization. A handful of contracts, about two hundred astronomical or astrological texts and two or three very fragmentary chronicles and Babylonian – Greek vocabularies constitute all the cuneiform literature in our possession for that period.

38

The last cuneiform text known so far – an astronomical ‘almanac’ – was written in

A.D

. 74 – 5.

39

It is quite possible that the Babylonian priests and astronomers continued for several

generations to write in Aramaic on papyrus or parchment, but no work of this kind is likely to be found. We know that some of the ancient temples were restored, that Ashur was worshipped in his home town and that a cult was rendered to Nabû in Barsippa until, perhaps, the fourth century

A.D

. But there is no evidence that Esagila, the temple of the former national god Marduk, was kept in repair. Indeed, Babylon probably suffered more damage in the repression which followed the revolt of a certain Hymeros in 127

B.C

., or in the civil war between Mithridates II and Orodes in 52

B.C

., than in the hands of Xerxes. When Trajan, in

A.D

. 115, entered the once opulent city, it was not to ‘take the hand of Bêl’, but to sacrifice to the

manes

of Alexander. Eighty-four years later, Septimus Severus found it completely deserted.

40

Very little is known of the administrative, social and economic status of Mesopotamia under the Sassanians (

A.D.

224 – 651). We learn from Greek and Latin authors that the northern part of the country was ravaged by four centuries of almost uninterrupted war between Romans (or Byzantines) and Persians

41

and that Assur was destroyed by Shapur I in

A.D.

256 as radically as it had been destroyed by the Medes. At Ctesiphon can be admired the remains of a magnificent palace attributed to Chosroes I while the more modest residence of another Sassanian king has been excavated at Kish.

42

At Uruk, not far from the city-wall originally built by Gilgamesh, a local ruler (?) was buried with his crown of golden leaves.

43

Sherds of Sassanian pottery testify to the occupation or reoccupation of other ancient sites. But at the beginning of the seventh century

A.D.

shortly before the Islamic conquest, the usual combination of military setbacks, internal strife and economic difficulties brought about the decline of the Sassanian kingdom and the ruin of Mesopotamia. Many canals left unattended dried up; the rivers, unchecked, could meander freely; scattering to outlying villages, people abandoned the towns deprived of water, and the ancient cities of Iraq were gradually buried beneath the sand of the desert and the silt of the valley. Those which survived were much damaged by the formation, in

A.D.

629, of the ‘Great Swamp’ that throughout the Middle Ages covered the whole area of ancient Sumer,

44

or by the terrible destructions systematically performed by the Mongols in the thirteenth century, or again, sadly, by the re-utilization of building materials by poor and or illiterate people to whom the history of ancient Iraq meant virtually nothing.

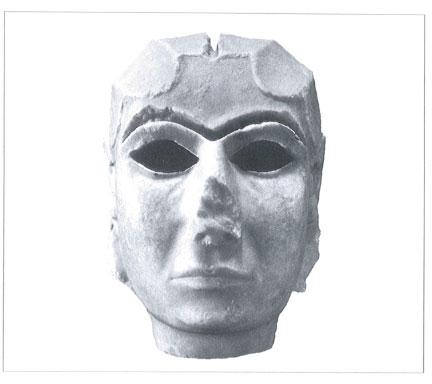

Alabaster head of a woman (or a goddess) found at Uruk. Proto-historic Uruk period (

c

. 3500

B.C.

)

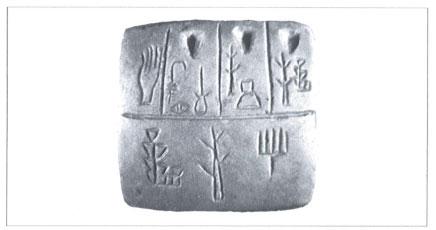

Archaic inscription on a clay tablet from proto-historic Uruk (

c

. 3300

B.C

.)

Caption

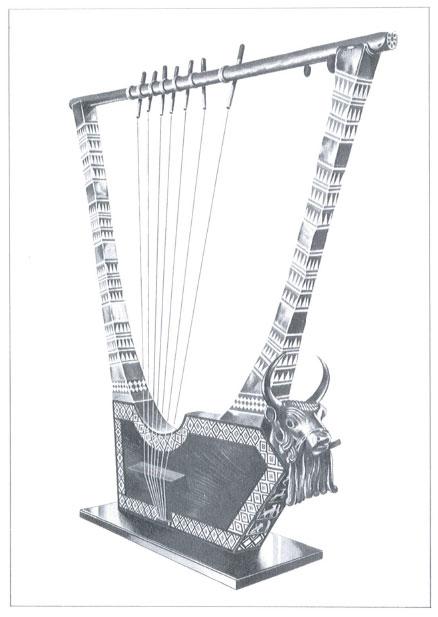

From the Royal Cemetery of Ur. A harp found in the ‘Great Death Pit’ and partly restored. Beneath the bearded bull's head, made of solid gold, is a set of shell plaques engraved with scenes of animal life

Head-dress and necklaces of a woman found in a collective tomb of the Royal Cemetery at Ur (

c

. 2600

B.C.

). The ornaments are made of gold, lapis-lazuli and cornelian