Ancient Iraq (45 page)

All the inhabitants of Babylon, as well as of the entire country of Sumer and Akkad, princes and governors, bowed to him (Cyrus) and kissed his feet, jubilant that he had received the kingship, and with shining faces happily greeted him as a master through whose help they had come to life from death and had all been spared damage and disaster, and they worshipped his name.

CHAPTER 24

Short as it was (626 – 539

B.C

.) the rule of the Chaldaean kings has left deep traces in the records of history. Monuments, royal inscriptions, letters, legal and commercial documents in great number concur to help us form of the Neo-Babylonian kingdom a fairly complete and accurate picture, and from this collection of data two main features emerge which give the whole period a character of its own: a religious revival combined with extensive architectural activity, and a resurgence of the temples as major social and economic units.

Geography, circumstances and the will of her rulers had turned Assyria into an expanding military nation. The same factors, acting through a thousand years of political abeyance, had made Babylonia the heir and guardian of Sumero-Akkadian traditions, the ‘sacred area’ of Mesopotamia, acknowledged as such and generally respected by the Assyrians themselves. A Babylonian renaissance in the sixth century

B.C.

was therefore bound to take the form of a religious revival. To the rebuilding of sanctuaries, the restoration of age-old rites, the celebration of religious festivals with increased ceremonial display, the Chaldaean kings devoted much time, energy and money. In their official inscriptions the stress was constantly laid on their architectural rather than their warlike performances. They could have claimed, like their predecessors, kingship over ‘the Universe’ of ‘the Four Quarters of the World’; they preferred to call themselves ‘Provider (

zaninu

) of Esagila and Ezida’

*

– a title which appears on thousands of bricks scattered throughout southern Iraq. Their colossal work of reconstruction involved

all the main cities of Sumer and Akkad, from Sippar to Uruk and Ur, but the capital-city was given, as expected, preferential treatment: rebuilt anew, enlarged, fortified and embellished, Babylon became one of the world's marvels. Jeremiah the prophet, while predicting its fall, could not help calling it ‘a golden cup in the Lord's hand, that made all the earth drunken’, and Herodotus, who is believed to have visited it

c

. 460

B.C

, admiringly proclaimed: ‘It surpasses in splendour any city of the known world.’

1

Was this reputation deserved or was it, as in other instances, the product of Oriental exaggeration and Greek credulity? The answer to this question should not be sought in the barren mounds and heaps of crumbling brickwork which today form most of this famous site, but in the publications of R. Koldewey and his co-workers, who, between 1899 and 1917, excavated Babylon on behalf of the Deutsche Orient Gesellschaft.

2

It took the Germans eighteen years of hard and patient work solely to recover the plan of the city in broad outline and unearth some of its main monuments, but we now possess enough archaeological evidence to complete, confirm or amend Herodotus's classical description and often share his enthusiasm.

Babylon, the Great City

Unquestionably, Babylon was a very large town by ancient standards. It covered an area of some 850 hectares, contained, we are told, 1,179 temples of various sizes, and while its normal population is estimated at about 100,000, it could have sheltered a quarter of a million people, if not more. The city proper, roughly square in plan, was bisected by the Euphrates, which now flows to the west of the ruins, and was surrounded by an ‘inner wall’. But ‘in order that the enemy should not press on the flank of Babylon’, Nebuchadrezzar had erected an ‘outer wall’, about eight kilometres long, adding ‘four thousand cubits of land to each side of the city’. The vast area comprised between these two walls was suburban in character, with mud-

houses and reed-huts scattered amidst gardens and palm-groves, and contained, as far as we can judge, only two official buildings: Nebuchadrezzar's ‘summer palace’, whose ruins form in the north-eastern corner of the town the mound at present called Bâbil, and perhaps the

bît akîtu

, or Temple of the New Year Festival, not yet exactly located.

Reinforced by towers and protected by moats, the walls of Babylon

3

were remarkable structures, much admired in antiquity. The inner fortified line surrounding the city proper consisted of two walls of sun-dried bricks, separated by a seven-metre wide space serving as a military road; its moat, about fifty metres wide, contained water derived from the Euphrates. The outer fortification, some eight kilometres long, was made of three parallel walls, two of them built of baked bricks. The spaces between these walls were filled with rubble and packed earth. According to Herodotus, the twenty-five metre wide top of this outer town wall could accommodate one or even two chariots of four horses abreast, enabling a rapid movement of troops from one end of the town to the other. When tested, however, this formidable defensive system proved useless: probably helped by accomplices in the city, the Persians entered Babylon through the bed of the Euphrates at low water and took it by surprise, proving that every armour has its faults and that the value of fortifications lies in the men behind them.

Eight gates, each of them named after a god, pierced the inner wall. The north-western gate, or Ishtar Gate, which played an important part in the religious life of the city, is fortunately the best preserved, its walls still rising some twelve metres above the present ground-level.

4

Like most city gates in the ancient Near East, it consisted of a long passage divided by projecting towers into several gateways, with chambers for the guard behind each gateway. But the main interest of Ishtar Gate resides in its splendid decoration. The front wall as well as the entire surface of the passage were covered with blue enamelled bricks on which stood out in relief red-and-white dragons (symbolic of Marduk) and bulls (symbolic of Adad), arranged

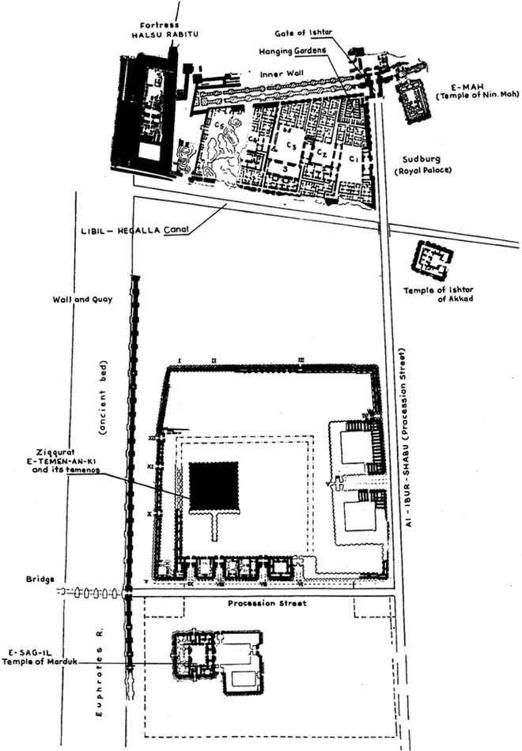

Caption

Plan of central Babylon.

Montage of the author after the plans of R. Koldewey

, Das wieder erstehende Babylon, 1925.

in alternating rows. Even the foundations were similarly decorated, although not with enamelled bricks. The total number of animal figures has been estimated at 575. The passage was roofed over, and the sight of these strange creatures shining in the dim light of torches and oil-lamps must have produced the most startling, awe-inspiring effect.

The Ishtar Gate was approached from the north through a broad, truly magnificent avenue called by the Babylonians

Ai-ibur-shabu

, ‘may the enemy not cross it’, but better known today as ‘Procession Street’. The avenue, more than twenty metres wide, was paved with slabs of white limestone and red breccia and was bordered by two thick walls which were no less impressive than those of the Gate, for on each side sixty mighty lions (symbolic of Ishtar) with red or yellow manes were cast in relief on blue ceramic. Behind these walls were three large buildings called by the Germans ‘Northern Citadel’ (Nord-burg), ‘Main Citadel’ (Hauptburg) and ‘Advanced Work’ (Vor-werk). All three formed part of the defensive system of the city, though the Hauptburg seems to have also been used as a royal or princely residence or as a kind of museum.

5

It ruins have yielded a number of inscriptions and sculptures ranging from the second millennium to the fifth century

B.C

., among which the basalt statue of a lion trampling on a man, known as ‘the lion of Babylon’. The origin of this colossal, roughly made piece of work is unknown, but foreign as it is to all that we know of Mesopotamian sculpture, it conveys such an impression of strength and majesty that it has become a symbol of the glorious past of Iraq. Beyond Ishtar Gate, Procession Street continued, somewhat narrower, through the city proper. It passed in front of the Royal Palace, crossed over a canal called

Libil hegalla

(‘may it bring abundance‘), skirted the vast precinct of the ziqqurat and, turning westwards, reached the Euphrates at the point where the river was spanned by a bridge of six piers shaped like boats. It divided the city into two parts: to the east lay the tangle of private houses (mound of Merkes),

6

to the west and south were grandiose palaces and temples.

Immediately behind the city-wall and close to the Ishtar Gate lay the ‘Southern Citadel’ (Südburg), ‘the House the marvel of mankind, the centre of the Land, the shining Residence, the dwelling of Majesty’ – in simpler words, the palace built by Nebuchadrezzar over the smaller palace of Nabopolas-sar, his father.

7

This very large building was entered from Procession Street through one single monumental gate and comprised five courtyards in succession, each of them surrounded by offices, reception rooms and royal apartments. The throne-room was enormous (

c

. 52 by 17 metres) and seems to have been vaulted. In contrast with the Assyrian palaces, no colossi of stone guarded the doors, no sculptured slabs or inscribed orthostats lined the walls. The only decoration – obviously intended to please the eye rather than inspire fear – consisted of animals, pseudo-columns and floral designs in yellow, white, red and blue on panels of glazed bricks. Of special interest was a peculiar construction included in the north-eastern corner of the palace. It lay below ground-level and was made of a narrow corridor and fourteen small vaulted cellars. In one of the cellars was found an unusual well of three shafts side by side, as used in connection with a chain-pump. It was extremely tempting to see in this construction the understructure of roof gardens, the famous ‘hanging gardens of Babylon’ described by classical authors and erected – so one legend tells us – by Nebuchadrezzar for the pleasure of his wife, the Median princess Amytis.

8

Recent excavations there have yielded less romantic results: these rooms merely served as stores for administrative tablets.

9

To the south of the royal palace, in the middle of a vast open space surrounded by a buttressed wall, rose the ‘Tower of Babel’, the huge ziqqurat called

E-temen-an-ki

, ‘the Temple Foundation of Heaven and Earth’. As old as Babylon itself, damaged by Sennacherib, rebuilt by Nabopolassar and Nebuchadrezzar, it was, as will be seen, completely destroyed, so that only its foundations could be studied by the archaeologists. Any reconstruction of Etemenanki therefore rests essentially

upon the meagre data yielded by these studies, upon the eyewitness description of Herodotus, and upon the measurements given in rather obscure terms in a document called ‘the Esagila tablet’.

10

It was certainly a colossal monument, 90 metres wide at its base and perhaps of equal height, with no less than seven tiers. On its southern side a triple flight of steps led to the second tier, the rest of the tower being ascended by means of ramps. At the top was a shrine (

sahuru

) ‘enhanced with bricks of resplendent blue enamel’, which, according to Herodotus,

11

contained a golden table and a large bed and was occupied by a ‘native woman chosen from all women’ and occasionally by Marduk, this statement being sometimes taken as referring to a ‘Sacred Marriage’ rite in Babylon, for which there is no other evidence.

E-sag-ila

, ‘the Temple that Raises its Head’, was the name given to the temple of Marduk, the tutelary god of Babylon and the supreme deity of the Babylonian pantheon since the reign of Hammurabi. It was a complex of large and lofty buildings and vast courtyards lying to the south of Etemenanki, on the other side of Procession Street and not at the foot of the ziqqurat, as did most Mesopotamian temples. All the kings of Babylon had bestowed their favours upon the greatest of all sanctuaries, and Nebuchadrezzar, in particular, had lavishly rebuilt and adorned ‘the Palace of Heaven and Earth, the Seat of Kingship’:

Silver, gold, costly precious stones, bronze, wood from Magan, everything that is expensive, glittering abundance, the products of the mountains, the treasures of the seas, large quantities (of goods), sumptuous gifts, I brought to my city of Babylon before him (Marduk).

In Esagila, the palace of his lordship, I carried out restoration work.

Ekua

, the chapel of Marduk, Enlil of the gods, I made its walls gleam like the sun. With shining gold as if it were gypsum… with lapis-lazuli and alabaster I clothed the inside of the temple…

Du-azag

, the place of the Naming of Destiny… the shrine of kingship, the shrine of the god of lordship, of the wise one among the gods, of the prince Marduk, whose construction a king before me had

adorned with silver, I clothed with shining gold, a magnificent ornament…

My heart prompts me to rebuild Esagila; I think of it constantly. The best of my cedars, which I brought from Lebanon, the noble forest, I sought out for the roofing of

Ekua

… Inside (the temple), these strong cedar beams… I covered with shining gold. The lower beams of cedar I adorned with silver and precious stones. For the building of Esagila, I prayed every day.

12

The wealth of Esagila is also emphasized by Herodotus who, having described the ziqqurat, speaks of a ‘lower temple’:

Where is a great golden image of Zeus (Marduk), sitting at a great golden table, and the footstool and chair are also of gold; the gold of the whole was said by the Chaldaeans to be of 800 talents' weight (3 tons). Outside the temple is a golden altar. There is also another great altar, whereon are sacrificed the full-grown of the flocks. Only sucklings may be sacrificed on the golden altar, but on the greater altar the Chaldaeans even offer a thousand talents' weight of frankincense yearly…

13

Twenty-three centuries after Herodotus visited Babylon however, the great temple of Marduk lay buried under more than twenty metres of earth and sand, making extensive excavations almost impossible. At the cost of a considerable effort, the Germans were able to unearth the main sanctuary (‘Hauptbau’) where, among the many rooms symmetrically arranged around a central courtyard, they identified

Ekua

, the shrine of Marduk, the smaller chapel of Marduk's consort, the goddess Sarpanitum and chapels devoted to other deities, such as Ea and Nabû. Of an adjacent building (‘Anbau’), only the outer walls and gates could be traced. Thoroughly plundered in antiquity, Esagila yielded practically no object of value. On top of the artificial hill that concealed it the tomb of 'Amran ibn 'Ali, a companion of the Prophet, perpetuates for the Moslems the sacred character attached to that part of Babylon.