Ancient Iraq (12 page)

CHAPTER 6

Whatever the real origin of the Sumerians, there is no doubt that their civilization sprang from the prehistory of Iraq itself. It reflected the mood and fulfilled the aspirations of the stable, conservative peasant society which has always formed the backbone of that country; it was ‘Mesopotamian’ in origin and in essence. For this reason, it survived the disappearance of the Sumerians as a nation in about 2000

B.C

. and was adopted and carried over with but little modification by the Amorites, Kassites, Assyrians and Chaldaeans who, after them, ruled in succession over Mesopotamia. The Assyro-Babylonian civilization of the second and first millennia is therefore not fundamentally different from that of the Sumerians, and from whatever angle we approach it we are almost invariably brought back to a Sumerian model.

This is particularly true of religion. For more than three thousand years the gods of Sumer were worshipped by Sumer-ans and Semites alike; and for more than three thousand years the religious ideas promoted by the Sumerians played an extraordinary part in the public and private life of the Mesopotamians, modelling their institutions, colouring their works of art and literature, pervading every form of activity from the highest functions of the kings to the day-to-day occupations of their subjects. In no other antique society did religion occupy such a prominent position, because in no other antique society did man feel himself so utterly dependent upon the will of the gods. The fact that the Sumerian society crystallized around temples had deep and lasting consequences. In theory, for instance, the land never ceased to belong to the gods, and the mighty Assyrian monarchs whose empire extended from the Nile to the Caspian Sea were the humble servants of their god Assur, just

as the governors of Lagash, who ruled over a few square miles of Sumer, were those of their god Ningirsu. This of course does not mean that economics and human passions did not play a part in the history of ancient Iraq, as they did in the history of other countries; but the religious motives should never be forgotten nor minimized. As an introduction to the historical periods which we are about to enter, a brief description of the Sumerian pantheon and religious ideas will surely not be out of place.

1

The Sumerian Pantheon

Our knowledge of Mesopotamian religious and moral ideas derives from a variety of texts – epic tales and myths, rituals, hymns, prayers, incantations, lists of gods, collections of precepts, proverbs, etc. – which come, in the main, from three great sources: the sacerdotal library of Nippur (the religious centre of Sumer), and the palace and temple libraries of Assur and Nineveh. Some of these texts are written in Sumerian,

2

others are usually Assyrian or Babylonian copies or adaptations of Sumerian originals, even though, in a few cases, they have no counterpart in the Sumerian religious literature discovered so far. The dates when they were actually composed vary from about 1900

B.C.

to the last centuries before Christ, but we may reasonably assume that they embody verbal traditions going back to the Early Dynastic period and possibly even earlier, since a number of Sumerian deities and mythological scenes can be recognized on the cylinder-seals and sculptured objects from the Uruk and Jemdat Nasr periods. Before these, positive evidence is lacking, but the unbroken continuity of architectural traditions, the rebuilding of temple upon temple in the same sacred area suggest that some at least of the Sumerian gods were already worshipped in southern Iraq during the Ubaid period.

The formulation of religious ideas and their expression as divine families and in myths were certainly slow processes, carried out by several ‘schools’ of priests simultaneously; but

somehow, in the end a general agreement on principles was reached, and while each city retained its own patron-god and its own set of legends, the whole country worshipped a common pantheon.

3

The divine society was conceived as a replica of the human society of Sumer and organized accordingly. The heavens, the earth and the netherworld were populated with gods – at first in hundreds but later less numerous owing to an internal syncretism that never reached monotheism. These gods, like the Greek gods, had the appearances, qualities, defects and passions of human beings, but they were endowed with fabulous strength, supernatural powers and immortality. Moreover, they manifested themselves in a halo of dazzling light, a ‘splendour’ which filled man with fear and respect and gave him the indescribable feeling of contact with the divine, which is the essence of all religions.

4

The gods of Mesopotamia were not all of equal status, but to classify them is not an easy task. At the bottom of the scale we would perhaps put the benevolent spirits and the evil demons who belonged more to magics than to religion proper, and the ‘personal god’, a kind of guardian angel attached to every person and acting as an intermediary between this person and the higher gods.

5

Then would come the humble deities who were responsible for such tools as the plough, the brick-mould or the pickaxe, and for such professions as potters, blacksmiths, goldsmiths and the like, as well as the gods of Nature in the broad sense of the term (gods of rivers, mountains, minerals, plants, wild and domesticated animals, gods of fertility, birth and medicine, gods of winds and thunderstorms), originally perhaps the most numerous and important as they personified ‘élan vital, the spiritual cores in phenomena, indwelling wills and powers’,

6

all concepts that are characteristic of the so-called primitive mentality. One step higher would be found the gods of the Netherworld, Nergal and Ereshkigal, side by side with warrior gods such as Ninurta. Above them the astral deities, notably the moon-god Nanna (called Sin by the Semites), who controlled time (the lunar months) and ‘knew the destinies of

all’ but remained in many ways mysterious, and the sun-god Utu (Shamash), the god of justice who ‘laid bare the righteous and the wicked’ as he flooded the world with blinding light. Finally, atop of the scale would naturally stand as dominant figures in the vast Mesopotamian pantheon the three great male gods An, Enlil and Enki.

An (Anu or Anum in Akkadian) embodied ‘the overpowering personality of the sky’ of which he bore the name, and occupied first place in the Sumerian pantheon. This god, whose main temple was in Uruk, was originally the highest power in the universe, the begetter and sovereign of all gods. Like a father he arbitrated their disputes and his decisions, like those of a king, brooked no appeal. Yet An – at least in the classical Sumerian mythology – did not play an important part in earthly affairs and remained aloof in the heavens as a majestic though somewhat pale figure. At some unknown period

7

and for some obscure reason the patron-god of Nippur, Enlil, was raised to what was in fact the supreme rank and became in a certain sense the national god of Sumer. Much later he himself was in turn wrested of his authority by the hitherto obscure god of Babylon, Marduk; but Enlil was certainly less of an usurper than Marduk. His name means ‘Lord Air’, which, among other things, evokes immensity, movement and life (breath), and Enlil could rightly claim to be ‘the force in heaven’ which had separated the earth from the sky and had thereby created the world. The theologians of Nippur, however, also made him the master of humanity, the king of kings. If An still retained the insignia of kingship it was Enlil who chose the rulers of Sumer and Akkad and ‘put on their heads the holy crown’. And as a good monarch by his command keeps his kingdom in order, so did the air-god uphold the world by a mere word of his mouth:

Without Enlil, the Great Mountain,

No city would be built, no settlement founded,

No stalls would be built, no sheepfolds established,

No king would be raised, no high priest born…

The rivers – their floodwaters would not bring over flow,

The fish in the sea would not lay eggs in the canebrake,

The birds of heaven would not build nests on the wild earth,

In heaven the drifting clouds would not yield their moisture,

Plants and herbs, the glory of the plain, would fail to grow,

In fields and meadows the rich grain would fail to flower,

The trees planted in the mountain-forest would not yield their fruit…

8

The personality of the god Enki is better known but much more complex. Despite the appearances, it is not certain that his Sumerian name means ‘lord earth’ (

en.ki

), and linguists are still arguing about the exact meaning of his Semitic name Ea. However, there is no doubt that Enki/Ea was the god of the fresh waters that flow in rivers and lakes, rise in springs and wells and bring life to Mesopotamia. His main quality was his intelligence, his ‘broad ears’ as the Sumerians said, and this is why he was revered as the inventor of all techniques, sciences and arts and as patron of the magicians. Moreover, Enki was the god who held the

me's

, a word used, it seems, to designate the key-words of the Sumerian civilization, and which also played a part in the ‘attribution of destinies’.

9

After the world was created, Enki applied his unrivalled intelligence to the laws devised by Enlil. A long, almost surrealist poem

10

shows him putting the world in order; extending his blessings not only to Sumer, its cattle sheds, fields and cities, but also to Dilmun and Meluhha and to the nomads of the Syro-Mesopotamian desert; transformed into a bull and filling the Tigris with the ‘sparkling water’ of his semen; entrusting a score of minor deities with specific tasks and finally handing over the entire universe to the sun-god Utu. This master architect and engineer who said that he was ‘the ear and the mind of all the land’ was also the god who was closest and most favourable to man. It was he who had the brilliant idea to create mankind to carry out the gods’ work, but also, as we shall see, who saved mankind from the Flood.

Side by side with the male pantheon there was a female

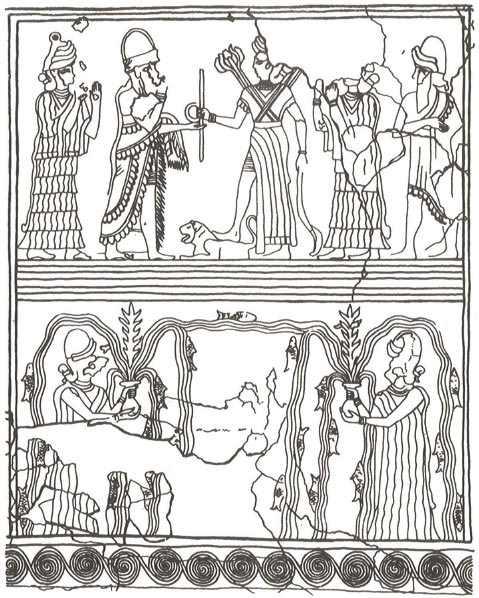

Mural painting from the second millennium palace at Mari. Above, the goddess Ishtar appoints Zimri-Lim king of Mari. by giving him the sceptre and the ring of kingship. Below, two unnamed goddesses holding vases spurting out water, as a symbol of fertility.

After A. Parrot

, Mission Archéologique de Mari,

II, 2, 1958

.

pantheon composed of goddesses of all ranks. Many of them were merely gods’ wives whilst others fulfilled specific functions. Prominent among the latter stood the mother-goddess Ninhursag (also known as Ninmah or Nintu), and Inanna (Ishtar for the Semites) who played a major role in Mesopotamian mythology.

Inanna was the goddess of carnal love and as such had neither husband nor children, but she entertained many lovers whom she regularly discarded. Beautiful and voluptuous as she undoubtedly was imagined and portrayed, she often acted perfidiously and had violent outbursts of anger which made this incarnation of pleasure a formidable goddess of war. In the course of time, this second aspect of her personality raised her to the rank of the male gods who led the armies into battle.11 Dumuzi, the only god she seems to have loved tenderly, probably resulted from the fusion of two prehistoric deities, for he was both the protector of herds and flocks and the god of the vegetation that dies in the summer and revives in the spring. The Sumerians believed that the reproduction of cattle and the renewal of edible plants and fruit could be secured only by a ceremony, on New Year's Day, in which the king, playing the role of Dumuzi, consummated a marital union with Inanna, represented by one of her priestesses. Love poems where overt erotism mixes with tender affection celebrate this ‘Sacred Marriage’,

12

while the ritual itself is described in some royal hymns, the most explicit of which is a hymn to Iddin-Dagan (1974-1954

B.C

.), the third king of the dynasty of Isin.

13

A scented bed of rushes is set up in a special room of the palace and on it is spread a comfortable cover. The goddess has bathed and has sprinkled sweet-smelling cedar oil on the ground. Then comes the King:

The King approaches her pure lap proudly,

He approaches the lap of Inanna proudly,

Ama‘ushumgalanna

*

lies down beside her,He caresses her pure lap.

When the Lady has stretched out on the bed, in his pure lap,

When the pure Inanna has stretched out on the bed, in his pure lap,

She makes love with him on her bed,

(She says) to Iddin-Dagan ‘You are surely my beloved‘.

Thereafter the people, carrying presents, are invited to enter, together with musicians, and a special meal is served:

The palace is festive, the King is joyous,

The people spend the day in plenty.

However, the rapports between Inanna and Dumuzi were not always harmonious, as shown by a famous text called ‘Inanna's descent to the Netherworld’ of which two versions have been preserved, one Sumerian, the other Assyrian.

14

In the Sumerian text Inanna goes down to the ‘land of no return’, casting off a piece of clothing or a jewel at each stage, in order to snatch this lugubrious domain from the hands of her sister Ereshkigal, the Sumerian equivalent of Persephone. Unfortunately, Inanna fails; she is put to death, then resurrected by Enki, but she is not allowed to return to earth unless she finds a replacement. After a long voyage in search of a potential victim, she chooses none other than her favourite lover. Dumuzi is promptly seized by demons and taken to the Netherworld, to the sorrow of his sister Geshtin-anna, the goddess of vines. Finally, Inanna is moved by Dumuzi's lamentations: she decides that he will spend one half of the year underground, and Geshtin-anna the other half.

The Sacred Marriage rite probably originated in Uruk, but it was performed in other cities, at least until the end of the dynasty of Isin (1794). After that date, Dumuzi fell to the rank of a relatively minor deity, although a month bore his name in its Semitic form Tammuz, and still bears it in the Arab world. In the last centuries of the first millennium

B.C.

, however, the cult of Tammuz was revived in the Levant. A god of vegetation more or less akin to Osiris, he became

adon

(‘the Lord’), i.e.

Adonis who died each year and was mourned in Jerusalem, Byblos, Cyprus and later even in Rome. In a Greek legend, Persephone and Aphrodite were quarrelling for the favours of the handsome young god when Zeus intervened and ruled that Adonis would share the year between the two goddesses.

15

Thus, the old Sumerian myth of Inanna's descent to the Netherworld had not been entirely forgotten: slightly distorted but recognizable, it had reached the Aegean Sea by some unknown channel, as did a number of Mesopotamian myths and legends.