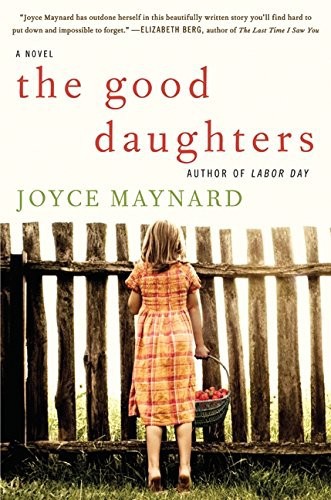

The Good Daughters

Read The Good Daughters Online

Authors: Joyce Maynard

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #Coming of Age, #Neighbors, #Farm life

Joyce Maynard

For Laurie Clark Buchar, Rebecca Tuttle Schultze,

Shirley Hazzard Marcello, and for Lida Stinchfield—all, like myself, daughters of New Hampshire (two native born, two transplanted).

Each a sister, not by blood but by choice.

Hurricane Season

October 1949

I

T BEGINS WITH

a humid wind, blowing across the fields from the northeast, and strangely warm for this time of year. Even before the wind reaches the house, Edwin Plank sees it coming, rippling over the dry grass, the last rows of cornstalks still standing in the lower field below the barn, the one place the tractor hasn’t got to yet.

In the space of time it takes a man to pour his coffee and call the dog in (though Sadie knows to come; the wind has sent her running toward the house), the sky grows dark. Crows circle the barn, and starlings, looking for the rafters. It’s not yet four o’clock, and daylight savings will be ending soon, but with the sun no longer visible behind the low, flat wall of cloud cover rolling in, it could be sunset, and maybe that’s why the cattle are making their long, low sounds of discontent. Things are not as they should be on the farm, and animals always know.

Standing on the porch with his coffee, Edwin calls to his wife, Connie. She’s still out in the yard with a basket, taking down the laundry she’d hung out to dry this morning. Four girls make a lot of laundry. Cotton dresses, Carter’s tops and bottoms, all pink, diapers, naturally—and her own sensible white cotton under-garments, but the less said about those the better, in Connie’s book.

Gathering up the last of the clothing not yet dry—rescued from the line before the wind gets to it—Connie is already thinking that if the lights go out due to the storm, as very likely they will, and he can’t listen to the ball game on the radio, her husband may bother her in bed tonight. She had been hoping the World Series would keep him occupied a while. His Red Sox won’t be playing; the team folded in September as usual. Still, Edwin never misses the series.

They knew the hurricane was coming. Bonnie, they’re calling this one

.

(In their eight years of marriage, has Edwin ever failed to catch the weather report?) He has already taken care of things in the barn, put away his tools, made sure the hay is covered and the barn doors secured. The cows are in their stalls, naturally. But on the roof, the weather vane—the same one that has stood there for a hundred and forty years now, through a half-dozen generations of Planks—spins like a top.

Now comes the rain. A few drops first, then sheets of it, pounding down so hard Edwin can no longer see his tractor, the old red Massey Ferguson that sits out in the field, in whatever spot he finished up his work that day. The rain’s so loud, he has to raise his voice now as he calls in his two elder daughters—Naomi and Sarah. “Go check your sisters, girls.” The little ones—Esther and Edwina—should be waking from their nap any time now, if the sound of the rain hasn’t wakened them already.

In the yard, Connie is struggling with the laundry basket—wind in her face, and rain. He sets his coffee down and runs to meet her and take the load. Already soaked, her dress clings to her short, utilitarian body. Nothing about her resembles the women he sometimes thinks about, afternoons on the tractor, or during the long hours he spends in the barn, milking—Marilyn Monroe, of course, Ava Gardner, Peggy Lee. But at that moment, with wet fabric accentuating her breasts, he is thinking how nice it will be, when the children are in bed tonight—knowing the game will be canceled due to the weather—to lie under the covers with his wife, hearing the rain on the roof. A good night for making love, if she lets him.

Connie hands her husband the basket. He puts his free arm around her

shoulders to help her up the hill—the wind is that strong pushing against their bodies. He has to raise his voice over the roar of the downpour.

“She’s a doozy, this one,” he says. “Looks like we may lose power.”

“I’d better get the girls,” she says, brushing his hand away. “The baby will be frightened.” She means Edwina, the one named after him. He might have thought he’d have been disappointed, not to get a boy that last time, and perhaps he was, but he loves his girls. There’s something about walking into church with the line of them—every one built like their mother, from the looks of things so far—that fills his heart with tender pride.

This is when the phone rings. Surprising that it even works in all this wind, and in another few minutes it won’t. But for now the dispatcher has managed to get through, to say a tree is down on the old County Road, and would Edwin get his truck out there, and a chain saw, so people can get through—not that anyone’s likely to try, until the storm dies down. Edwin is the captain of the volunteer firemen in town, and on call at moments like these when a job needs doing.

He has his work boots on already. Now comes the yellow slicker and a check to make sure that the batteries in his flashlight are working. A final shot of coffee in case the task takes longer than he hopes. A kiss for his wife, who turns her cheek to receive it with her usual brisk efficiency. She is already lighting the stove to put the beans on for the children.

Less than five minutes have passed since the phone rang, but the sky has gone black, and the wind is wailing. Edwin climbs into the cab of his truck and starts the motor. Even with the wipers on, the only way he makes it down the road is because he knows it so well—he could drive this stretch blindfolded.

The radio is playing. Peggy Lee, oddly enough, the woman he had just been thinking about not one hour ago, bringing the cattle into the barn. There’s a woman for you. Imagine making love to a gal like that.

They interrupt the broadcast. Hurricane warnings upgraded to full-scale storm emergency status. Power lines coming down all over the county. No drivers on the road, except for rescue workers. He is one of those.

It will be a long night, Edwin knows. Before it’s over, he will be soaked

through to his long johns. There’s danger for a man out in a storm like this one, too. Falling trees, loose power lines on the road. Floodwaters.

He thinks about a movie he saw once—one of the few times he ever went to the pictures, in fact—

The Wizard of Oz

. And how, when the storm hit (a twister, if memory serves), the farmhouse lifted right up off the ground and landed in this whole other place nobody ever knew about before.

That was a made-up story, of course, but wild weather can come upon a person in the state of New Hampshire, too. Right around the time he saw the Judy Garland movie, in fact, they had the biggest storm in a hundred years, the hurricane of ’38. That one took the oak tree in front of the house where his tire swing used to hang. And a few hundred others. A few thousand, more like it. Even now, all these years later, people around here still talk about that storm, measure time even, by “before ’38” or “after.”

From the looks of it, this hurricane could do some serious damage. He does an inventory of the places on the farm where they might run into trouble. No danger of losing crops this time of year (with only the pumpkins left in the field, and not many of those), but there’s the barn roof, and the shed, and a stand of hickory he loves, up along the strawberry fields. Always the first to go in a storm, hickory. He’d hate to see those trees snapped off, and it could happen tonight.

Then there’s the house, built by his great-grandfather, and still standing firm, with those four little girls and his good wife inside. He doesn’t like leaving them alone in a storm.

Still, making his way along the darkened road, with the rain coming down in sheets and the body of his old Dodge trembling from the wind, Edwin Plank registers an oddly pleasant sense of anticipation. One thing about a hurricane: it turns everything upside down. You never know how things will be once the wind dies down. All you know for sure: the world will look different tomorrow. And perhaps it is a sign of some restlessness in his nature, or more than that even, a hunger for something he has not yet found, that Edwin Plank heads out into the wild night with his heart beating fast. Life on this patch of earth could be totally different come morning.

Beanpole

M

Y FATHER TOLD

me I was a hurricane baby. This didn’t mean I was born in the middle of one. July 4, 1950, the day of my birth, fell well before hurricane season.

He meant I was conceived during a hurricane. Or in its aftermath.

“Stop that, Edwin,” my mother would say, if she overheard him saying this. To my mother, Connie, anything to do with sex, or its consequences (namely, my birth, or at least the idea of linking my birth to the sex act), was not a topic for discussion.

But if she wasn’t around, he’d tell me about the storm, and how he’d been called out to clear a fallen tree off the road, and how fierce the rain had been that night, how wild the wind. “I didn’t get to France in the war like my brothers,” he said, “but it felt like I was doing battle, fighting those hundred-mile-an-hour gusts,” he told me. “And here’s the funny thing about it. Those times a person feels most afraid for their life? Those are the times you know you’re alive.”

He told me how, in the cab of his truck, the water poured down so hard he couldn’t see, and how fast his heart was pounding, plunging into the darkness,

and how it was, after—outside in the downpour, cutting the tree and moving the heavy branches to the side of the road, his boots sinking into the mud and drenched from rain, his arms shaking.

“The wind had a human sound to it,” he said, “like the moaning of a woman.”

Later, thinking back on the way my father recounted the story, it occurred to me that much of the language he used to describe the storm might have been applied to the act of a couple making love. He made the sound of the wind for me, then, and I pressed myself against his chest so he could wrap his big arms around me. I shivered, just to think of how it must have been that night.

For some reason, my father liked to tell this story, though I—not my sisters, not our mother—was his only audience. Well, that made sense perhaps. I was his hurricane girl, he said. If there hadn’t been that storm, he liked to say, I wouldn’t be here now.

It was nine months later almost to the day that I arrived, in the delivery room of Bellersville Hospital, high noon on our nation’s birthday, right after the end of the first haying season, and just when the strawberries had reached their peak.

And here was the other part of the story, well known to me from a hundred tellings: small as our town was—not even so much as a town, really; more like a handful of farms with a school and a general store and a post office to keep things ticking along—I was not the only baby born at Bellersville Hospital that day. Not two hours after me, another baby girl came into the world. This would be Dana Dickerson, and here my mother, if she was in earshot, joined in with her own remarks.

“Your birthday sister,” she liked to say. “You two girls started out in the world together. It only stands to reason we’d feel a connection.”

In fact, our families could hardly have been more different—the Dickersons and the Planks. Starting with where we made our home, and how we got there.

The farm where we lived had been in my father’s family since the sixteen

hundreds, thanks to a twenty-acre land parcel acquired in a card game by an ancestor—an early settler come from England on one of the first boats—with so many greats in front of his name I lost count, Reginald Plank. Since Reginald, ten generations of Plank men had farmed that soil, each one augmenting the original tract with the purchase of neighboring farms, as—one by one—more fainthearted men gave up on the hard life of farming, while my forebears endured.

My father was the oldest son of an oldest son. That’s how the land had been passed down for all the generations. The farm now consisted of two hundred and twenty acres, forty of them cultivated, mostly in corn and what my father called kitchen crops that we sold, summers, at our farm stand, Plank’s Barn. Those and his pride and joy, our strawberries.

Ours was never a family with money, but we had mortgage-free land, which we all understood to be the most precious thing a farmer could possess, the only thing that mattered other than (and here came my mother’s voice) the church. (And we had standing in the town that came from having history in a place where not just our father’s parents and grandparents, but their great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents before them, all lay buried in New Hampshire soil.) More than any other family in town that was what made us who we were—history and roots.

The Dickersons had drifted into town (my mother’s phrase once more) a few years back from someplace else. Out of state was all we knew, and though they owned a place—a run-down ranch house out by the highway—it was clear they were not country people. Besides Dana, they had an older boy, Ray—lanky and blue-eyed—who played the harmonica on the school bus and once, famously, arranged himself on the tar of the playground at recess, motionless and staring blankly in the direction of the sky, as if he’d jumped out a window. The teacher on duty had already called the principal to summon an ambulance when he hopped up, dancing like Gumby, all rubber legged and grinning. He was a joker and a troublemaker, though everybody loved him, particularly the girls. His badness thrilled and amazed me.

Supposedly, Mr. Dickerson was a writer, and he was working on a novel, but until that sold he had a job that took him on the road a lot—selling different kinds of brushes out of a suitcase, my mother thought—and Valerie Dickerson called herself some kind of artist—a notion that didn’t sit well with my mother, who believed the only art a woman with children had any business pursuing was the domestic variety.

Still, my mother insisted on paying visits to the Dickersons whenever we were in town. She’d stop by with baked goods or, depending on the season, corn, or a bowl of our fresh-picked strawberries, with biscuits hot out of the oven for shortcake. (“Knowing Valerie Dickerson,” she said, “I wouldn’t put it past that woman to use whipped cream in a can.” The idea that Val Dickerson might serve her shortcake with no cream at all—real or fake—seemed more than she could envision.)

Then the women might visit—my mother in her sensible farm dress, and the same blue sweater that stayed on her for my entire childhood, and Val, who wore jeans before any other woman I’d met, and served only instant coffee, if that. She never seemed particularly happy to see us, but fixed my mother a cup anyway, and a glass of milk for me or, because the Dickersons were health food nuts, some kind of juice made out of different vegetables all whirled up together in a machine Mr. Dickerson said was going to be the next big thing after the electric fry pan. I hadn’t known the electric fry pan was such a big idea, either, but never mind.

Then they moved away, and you would have imagined that was the end of our family’s association with the Dickersons. Only it wasn’t. Of all the people who’d come in and out of our lives over the years—helpers on the farm, customers at Plank’s, even my mother’s relatives in Wisconsin—it was only the Dickersons with whom she made a point of not losing touch. It was as if the fact that Dana and I were born on the same day conferred some sort of rare magic on the relationship.

“I wonder if that Valerie Dickerson ever feeds Dana anything besides nuts and berries,” my mother said one time. The family had moved to Pennsylvania by now, but they’d been passing through—and because it was strawberry sea

son, and our birthdays, they’d stopped by the farm stand. Dana and I must have been nine or ten, and Ray was probably thirteen, and tall as my father. I was bringing in a load of peas I’d spent the morning picking when he spotted me. It was always an odd thing—how, even when I was young, and the difference between our ages seemed so vast, he always paid attention to me.

“You still making pictures?” he said. His voice had turned deep but his eyes were the way I remembered, and looking at me hard, like I was a real person and not just a little girl.

“I was reading this in the car,” he said, handing me a rolled-up magazine. “I thought you’d like it.”

Mad

magazine. Forbidden in our family, but my favorite.

It was on this visit—the first of what became a nearly annual tradition of strawberry runs—where the word had come out that Valerie was now a vegetarian. This was back in the days when it was almost unheard of for a person not to eat meat. This fact shocked my mother, as so much about the Dickersons did.

“Some say the American consumer eats too much beef,” my father said—a surprising view for a farmer to set forward, even if his main crop was vegetables. My father liked his steak, but he possessed an open mind, whereas anything different from how we did things appeared suspect to my mother.

“Dana seems like a particularly intelligent girl, didn’t you think, Edwin?” she said, after they pulled away, in that amazing car of Valerie’s, a Chevrolet Bel Air with fins that seemed to me like something you’d expect to be driven by a movie star, or her chauffeur. Then, to me, she mentioned that my birthday sister had won their school spelling bee that year, and was also enrolled in the 4-H Club, working on a project involving chickens.

“Maybe it’s about time you thought about 4-H,” she said to me.

This kind of remark—and there were many such—no doubt formed the basis for my early resentment of Dana Dickerson. As the two of us moved through childhood and then adolescence, the girl seemed to provide the standard against which my own development and achievements should be measured. And when this happened, I could pretty much rely on falling short, in anything but the height category.

Most of the time, of course—given the irregularity of the reports—we didn’t know where things stood with Dana Dickerson. Then my mother made do with speculating. When I learned to ride a bike, my mother had commented, “I wonder if Dana can do that yet,” and when I got my period—early, just after turning twelve—she considered what might be going on for Dana now. One time, on my birthday—mine and Dana Dickerson’s—my mother gave me a box of stationery with lilacs going up the side. “You can use this to write letters to Dana Dickerson,” she said. “You two should be pen pals.”

I didn’t write. If there was one girl in the world I didn’t want to correspond with, that girl would be Dana Dickerson. Our families had nothing in common and neither did we.

The one Dickerson who interested me was Dana’s older brother, Ray, four years older than us. He was a tall, impossibly long-limbed person, like his mother, Valerie, and though he wasn’t handsome in the regular way of high school boys you saw on TV (Wally Cleaver and the older brothers on

My Three Sons,

or Ricky Nelson), there was something about his face that made my skin hot if I looked at him. He had blue eyes that always gave you the sense he was about to burst out laughing, or cry—by which I mean, I suppose, that there was always so much feeling evident—and eyelashes so long they shaded his face.

Ray had this way of coming into a room that took your breath away. Partly it was the look of him, but more so it was his crazy energy, and all the funny and amazing ideas he thought up. He did things other boys didn’t, like building a raft out of old kerosene drums and taking it down Beard’s Creek, where it got stuck in the mud, and performing magic tricks wearing a cape he’d evidently sewed himself. He had taught himself ventriloquism, so one time, at Plank’s, he made this pair of summer squashes talk to each other without moving his lips. Years before, when I was five or six, he pulled a silver dollar out of my ear, so for the next few days I was forever checking to see what else might be in there, but nothing ever was.

One spring Ray Dickerson built a homemade unicycle using a few old bike parts he’d found at the dump. That was Ray for you. When other boys were out

on the ball field, he rode that contraption around town playing his harmonica.

At one point, he’d tried to teach his sister how to ride the unicycle, and Dana had taken a fall bad enough that her arm ended up in a sling. You’d think Mrs. Dickerson would have confiscated the thing after that—or that she’d be upset at least, but it didn’t seem to bother her, though my mother had a fit.

Not much bothered Val Dickerson, or appeared to. She was an artist, and generally absorbed in that more than whatever might be going on with her children, was my impression. Where my mother kept close tabs on every single thing my sisters and I did, Val Dickerson would disappear into a room she called her studio for hours at a time, leaving Dana and Ray with an enormous bowl of dry Cheerios and some odd assignment like “go put on a play” or “see if you can find a squirrel and teach him to do tricks.” The strange thing was, they might. When Ray talked to animals, they seemed to listen.

My father couldn’t ever take time off in summer, because of all the jobs that needed doing at our farm, but my mother established a tradition of making a road trip every year during February vacation, when there wasn’t so much that needed doing on the farm, and what there was he could, reluctantly, trust to his helper, a small, wiry boy by the name of Victor Patucci who’d first shown up at our door when he was only fourteen or so, looking for work. Victor was about as unlikely a person as you could have chosen to be a farmer—a smoker, who wore so much Brylcreem his hair reflected light, who followed race car driving and turned up his transistor radio whenever they played an Elvis Presley song, and never seemed to go to school. His father worked in the shoe factory, and my father said he wasn’t a good man—words that stood out for me because my father so seldom spoke ill of anyone.

“The boy could use a helping hand,” my father said when he’d signed Victor up—and though initially my mother protested the thirty-dollar-a-week expense, it was Victor’s presence on our farm that made our annual Dickerson visit possible, and for that she was thankful.

So every March we set out to see the Dickersons. Before embarking on our road trip, my mother filled a cooler with sandwiches and jars of peanut butter

and things like beef jerky that didn’t go bad. Then my sisters and I would pile into the backseat of our old Country Squire station wagon with the fake wood paneling and a stack of coloring books and Mad Libs to keep us busy. We’d play I Spy or look for license plates from unusual states and now and then we’d stop at battlefields and historic monuments, and sometimes a museum, but our ultimate destination was whatever run-down house or trailer (and one time, a converted Quonset hut) the Dickersons were living in that year.