An Empire of Memory (34 page)

Read An Empire of Memory Online

Authors: Matthew Gabriele

Tags: #History, #Medieval, #Social History, #Religion

91 ‘In a manner reminiscent of Uzzah’s sudden death for touching the Ark of Yahweh (2 Samuel

6:6–7), the maiming of [the canon] demonstrates the potency of Charlemagne as relic.’ Nichols,

Romanesque Signs, 68.

92 Callahan, ‘Problem of “Filioque”’, 115. The sketches are also discussed in Danielle Gaborit-

Chopin, ‘Les Dessins d’Adémar de Chabannes’, Bulletin Archéologiqe du Comité des Travaux

Historiques et Scientifiques, 3 (1967), 217–18.

122

The Franks Recreate Empire

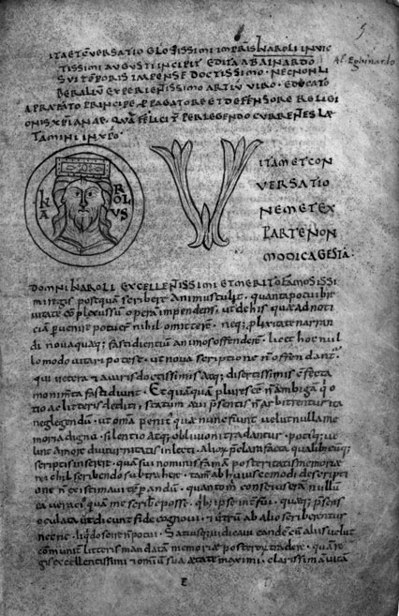

Figure 4.2. Paris, BnF lat. 5943A, fo. 5r with drawing of Charlemagne by Ademar of

Chabannes. Image courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France.

happened and as Ademar presents it––was staged so that it had a powerful effect on

the Charlemagne legend, helping to create the idea that Charlemagne was still alive

(albeit in suspended animation) within his tomb.

Paul Dutton has elegantly demonstrated that the convention of the sleeping

ruler––a ruler whom death has taken, but not completely––had its origins in the

decades just after Charlemagne’s death, when the Franks pined for the (perceived)

glory of his reign. Charlemagne as sleeping emperor in turn blended seamlessly with

the legend of the Last Emperor because ‘people preferred to believe in [Charle-

magne’s] energetic insomnia . . . , [for it] opened up a domain wherein dead

emperors might still breathe life into an old and troubled world’.93 Otto III seemed

to find Charlemagne resting, still on his throne. In the late 1020s, Ademar of

93 Paul Edward Dutton, The Politics of Dreaming in the Carolingian Empire (Lincoln, Neb., 1994),

14–15 (quotation at 15); Folz, Souvenir, 93.

The Franks’ Imagined Empire

123

Chabannes thought Charlemagne waited patiently in his tomb to re-emerge. The

eleventh-century Exhortatio ad proceres regni refers to a future utopia where Rome

will arise to rule all peoples, and Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Charlemagne will

return to renew the world under the keys of St Peter.94 At the end of the eleventh

century, the Oxford Roland had Charlemagne symbolically re-emerge, blazing forth

from passivity to vigorous activity. During the First Crusade, rumors circulated that

Charlemagne had indeed risen from the dead to help retake Jerusalem for the

Christians.95

At about that same time, around the time of the First Crusade, contemporary to

Benzo’s Ad Heinricum, the Descriptio qualiter, Charroux’s Historia, and the Oxford

Chanson de Roland, an anonymous scribe created a new version of Adso’s tenth-

century De ortu et tempore Antichristi.96 Adso’s original tract drew heavily on

Carolingian symbols of power in portraying his vision of the Last Emperor. Indeed,

Daniel Verhelst has suggested that these Carolingian echoes in Adso’s prophetic

vision may in part account for the subsequent popularity of his tract because that

vision ‘evoked in [its readers], with a certain nostalgia . . . , memories of the

idealized empire of the Franks under Charlemagne, where “real” peace reigned’.97

The eleventh-century revision of Adso’s treatise, called Pseudo-Alcuin for reasons

that will shortly become apparent, amplified these Carolingian echoes by creating

something quite novel. Here, the vibrant eleventh-century traditions of antichrist,

pilgrimage, Charlemagne, and christomimetic Last Emperor are combined into a

coherent narrative.98

Pseudo-Alcuin begins by retelling a version of the antichrist’s life taken almost

directly from Adso’s original letter to Queen Gerberga, including details of anti-

christ’s birth, his arrival at Jerusalem, the subsequent persecutions of the Christians

94 Exhortatio ad proceres regni, ed. E. Dümmler, Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für ältere deutsche

Geschichtskunde, 1 (1876), 177. Folz claimed that, slightly before the Exhortatio’s composition, a poem by Anselme de Bésate asserted that ‘Charlemagne will reign anew’ at some point in the near future.

Folz, Souvenir, 141. I have, however, been unable to find Folz’s source.

95 Paul Alphandéry reports that an East Frankish legend held that Charlemagne was sleeping in a

mountain, waiting to re-emerge in order to return the empire to glory. Paul Alphandéry and Alphonse

Dupront, La Chrétienté et l’idée de croisade (Paris, 1954), 76, 78, 131. For a more full discussion of the idea of Carolus redivivus in the 11th cent. (without mention of the Last Emperor legend), see Nichols, Romanesque Signs, 66–94.

96 There are at least eight distinct revisions of Adso’s original text. See De ortu, ed. Verhelst; and Möhring, Der Weltkaiser der Endzeit, 360–8.

97 Verhelst, ‘Adso’, 86. On the Carolingian echoes, see Verhelst, ‘La Préhistoire’, 95, 101; Konrad,

De ortu et tempore Antichristi, 98–9; and Alphandéry and Dupront, Chrétienté, 24.

98 Pseudo-Alcuin dates to the late 11th cent., but before Clermont (1095) and the First Crusade.

See De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 109–10; Folz, Souvenir, 141–2; and Catalogue général des manuscrits des

bibliothèques publiques de France: Chartres, 63 vols. (Paris, 1890), xi. 58–60. Verhelst calls Pseudo-

Alcuin not ‘a copy with some interpolations, but a manifestly intentional [second-generation]

adaptation’ of Adso’s original treatise. By ‘second-generation’, I mean that the Pseudo-Alcuin is

actually an adaptation of the anonymous Descriptio cuiusdam sapientis de Antichristo, which is in turn adapted from Adso’s original treatise. See the stemma printed in De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 32. On its status as a novel work, see De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 106. Pseudo-Alcuin can be found in eighteen extant

manuscripts, dating from the 12th to the 15th cent. Manuscript summary in De ortu, ed. Verhelst,

110–16. Most (though not all) of the earliest manuscripts are from West Francia.

124

The Franks Recreate Empire

there, and the false miracles he will perform. Pseudo-Alcuin then, in the first of two

separate discussions of the Last Emperor, revisits Adso’s procession of the world

regna, from the Greeks, to the Persians, to the Romans. In a standard trope, Rome

will be the last and mightiest of these kingdoms, still holding off the antichrist’s

arrival because, although Roman rule has almost totally been destroyed, the Franks

rightfully held power. The last and greatest of these rulers of the last and mightiest

of these kingdoms will be a Frank, who will travel to Jerusalem at the end of his

reign in order to turn over Christian and Roman imperial authority to God on the

Mount of Olives.99

The second section of Pseudo-Alcuin dealing with the Last Emperor has no

precedent in either Adso’s work or any of its subsequent revisions. As the sibylline

books say, Pseudo-Alcuin relates, the Last Emperor, this king of the Romans who

holds universal imperial authority (imperium), will be named ‘C.’ While this ‘C.’

reigns, the hordes of Gog and Magog will suddenly re-emerge from the north,

forcing the king of the Romans to conquer the whole world. The Last Emperor ‘will

therefore devastate all the islands and cities of the pagans, destroy their idolatrous

temples, and bring them to baptism. The cross of Christ will be displayed in every

temple. The Jews will then be converted to the Lord.’ After a reign of 112 years, ‘C.’

will finally go to Jerusalem, put down his diadem, give over his Christian––not

Roman––kingdom to God, and thus Christ’s ‘sepulcher will be glorious’.100 Elias

and Enoch will then appear, as the world will have been prepared for the coming of

antichrist and the final stages of the end of the world.

Both sections dealing with the Last Emperor are complementary, together

offering the reader clues to his identity. The most obvious clue is that his name

will begin with the letter ‘C’. The Tiburtine Sibyl had called the Last Emperor

‘Constans’, a king of the Romans and Greeks. Pseudo-Alcuin, however, eliminates

all reference to the Greeks, designating the Last Emperor solely as rex Romanorum,

more specifically ‘one from the kings of the Franks [who] will hold Roman

authority anew (ex integro)’.101 This rather strange construction appears to mean

that the Last Emperor will be a Frankish king or a descendant of Frankish kings,

but significantly a Frank who has already ruled––i.e. that there have been a certain

99 Pseudo-Alcuin, Vita Antichristi ad Carolum Magnum, in De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 122–3. Pseudo-

Alcuin seems to be using imperium a bit more insistently than Adso, emphasizing again and again that

the Last Emperor will possess universal imperial authority.

100 ‘Sicut ex sibyllinis libris habemus, tempore predicti regis, cuius nomen erit C. rex Romanorum

totius imperii. . . . Tunc exsurgent ab aquilone spurcissime gentes, quas Alexander rex inclusit in Goch et Magoch. . . . Quod cum audierit Romanorum rex, conuocato exercitu, debellabit eos et prosternet

eos usque ad internecionem. . . . Rex Romanorum omne sibi vindicet regnum terrarum. Omnes ergo

insulas et civitates paganorum deuastabit et uniuersa idolorum templa destruet et omnes paganos ad

baptismum conuocabit, et per omnia templa crux Christi dirigetur. Iudei quoque tunc convertentur ad

Dominum. . . . Impletis autem centum duodecim annis regni eius, ueniet Hierosolimam, et ibi, ut

dictum est, deposito diademate, relinquet Deo Patri et Filio eius Christo Iesu regnum christianorum et erit sepulchrum eius gloriosum [Isa. 11: 10].’ Pseudo-Alcuin, Vita Antichristi, in De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 125. Pseudo-Alcuin is speaking of the Tiburtine Sibyl, on whose account the he draws heavily.

101 ‘Unus ex regibus Francorum Romanum imperium ex integro tenebit.’ Pseudo-Alcuin, Vita

Antichristi, in De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 123. On the translation of ex integro, see above at n. 48. On the text’s similarities to the Tiburtine Sibyl, see De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 107.

The Franks’ Imagined Empire

125

number of Frankish kings until this time and the Last Emperor will be one of them.

The word ‘anew’ suggests that the Last Emperor will be a Frankish ruler who has

already lived and who will re-emerge in the Last Days to again hold Roman

authority so that he can ‘conquer all the kingdoms of the world’ and hand all of

Christendom over to God at the very end.102 Only one figure, whose name will be

‘C.’, possessed all these characteristics. The text’s incipit––Vita Antichristi ad

Carolum Magnum ab Alcuino edita––seems to be original and is very clear as to

its supposed author (Alcuin) and dedicatee (Charlemagne).103 Writing just before

the First Crusade, Pseudo-Alcuin’s Last Emperor was Charlemagne.

Verhelst has argued that the legends of the Last Emperor and Charlemagne

developed parallel to each other in the early Middle Ages.104 ‘Parallel’ is not the

right word though, for the two legends most certainly intersected. This intellectual

connection between the legends of Charlemagne and Last Emperor may stem in

part from the reigns of Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, for it now seems clear

that at least some in their court circles thought that one or the other of them might

have been the Last Emperor and thus tried to make their actions echo prophecy.105

There is no direct evidence that either Charlemagne or Louis knew the Latin or

Greek versions of the Last Emperor legend directly, but they had been circulating

the West since the middle of the eighth century and early ninth-century writings

are suggestive. For instance, Ambrosius Autpertus (d. 784), Alcuin (d. 804), and

(later) Haimo of Auxerre all have shown their familiarity with Pseudo-Metho-

dius.106 Moreover, modern scholars, especially Juan Gil, Wolfram Brandes,

Hannes Möhring, and Johannes Heil, have done much to illuminate the apocalyp-

tic concerns of the late eighth and early ninth centuries more generally. Some have

focused on Charlemagne’s coronation as emperor in 800, occurring as it did in

6000 AM (annus mundi), while others have shown that this date was just an

‘additional element in a larger eschatological context’.107 For instance, the Frankish

102 ‘Rex Romanorum omne sibi vindicet regnum terrarium. . . . relinquet Deo Patri et Filio eius

Christo Iesu regnum christianorum’. Pseudo-Alcuin, Vita Antichristi, in De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 125.

103 The incipit appears in the earliest manuscript, which was 11th cent. and from Saint-Pierre de

Chartres (though the manuscript was destroyed in the Second World War). De ortu, ed. Verhelst, 110.

104 Verhelst, ‘La Préhistoire’, 101.

105 Wolfram Brandes, ‘Tempora Periculosa Sunt: Eschatologisches im Vorfeld der Kaiserkrönung