An Economy is Not a Society (3 page)

Read An Economy is Not a Society Online

Authors: Dennis; Glover

Instead, Barry stops me and points to a shallow drain running through rough concrete across a vast open space that is now used as a car park. This was once the floor under the assembly line roof, which stretched far and wide around us, the same area as three Melbourne Cricket Grounds. As shrines go, it's not much, but then most shrines are essentially about the dead things that lie under the ground, and it was enough to rouse in me at least a smidgen of emotion.

A few years earlier I had walked seven miles in the driving autumn rain across the Scottish island of Jura to find the farmhouse in which the dying George Orwell had written

Nineteen Eighty-Four.

It was a walk at times I thought would never end, or that would end with me being mistaken for a wild stag and shot by one of the many hunters roving the hillsides. But I can recall the moment I rounded a bend and saw the white stone house appear, just like the white whale had appeared to Captain Ahab, and the way my heart had quickened and my confidence returned. This feeling was the same. Yes, it's just the site of an old factory, and one no longer even really there, but this is where my family's modest affluence was earned and where Australia's egalitarian dream came closest to fulfilment before the economic reformers threw cold water in our faces. Such places are just as important as any disused mine or former bank building.

Inside the new warehouse, up in Barry's office, you get a top-tier view of what's replaced the assembly line. It's actually quite spectacular, and it's almost hard to believe that the old assembly line building was half as big again as this. Around 150 people now work on the floor, and another 100 or thereabouts in administration â a fraction of the old payroll list. Barry, who is an expert in warehousing â which I find to be a far more sophisticated industry than I had imagined â quickly estimates the floor sizes of the new buildings springing up on the old GMH site, and calculates that the entire site will be lucky to ever reach 400 jobs, in addition to those at HSPO â a net loss of just under 4000 unionised, well-paid and mostly skilled and semi-skilled working-class jobs to the Dandenong and Doveton area from this site alone. You don't have to be a statistician to draw some important conclusions from that.

Barry generously takes me down onto the floor. As we wander around the vast, quiet space, it is obvious this is still a good place to work â safe, clean, calm, polite and unhurried. It seems efficient in the proper sense of getting things done, rather than in the modern managerialist sense of making people redundant. We see where the trucks bring in containers and pallets of spare parts each morning, where the forklifts take them to the endless rows of scientifically arranged shelves (which remind me of the last scene in

Raiders of the Lost Ark),

and where the ordered parts are sent to dealers and repair centres in the afternoon.

The managers seem a decent lot; it's more like an office than a factory. And yet ⦠something's missing. What is it? The movement, the noise, the urgency and pace; the energy-sapping overtime that you need an extra-long sleep on Saturday to recover from but which can double your weekly pay packet; even the conflict, the union meetings and the strikes â all are gone. What's missing is the sense of work and life as being more than a tranquil, powerless, well-ordered, well-behaved and highly productive shuffle to the grave.

Work and life should be more than this. They should involve an assertion of rights, a sense of power, a feeling of being part of something bigger â a movement to change things for the better. In an era that has lost religion, life itself should have this sort of religious dimension. It's as if the new economy has done a deal with its workforce: a little more pay in return for your pride, purpose, freedom and the jobs of your friends. It's like one of those H. G. Wells utopias, in which everyone appears happy but bored, and all the hard work is being done by a race of helots hidden somewhere deep underground; in our case, I guess that means in China.

I imagine all sorts of people will know what I mean â journalists missing the once mad activity of the newspaper office, with its drinking and deadlines and passions; aircrew watching their aircraft being piloted by computers; Japanese waiters watching food being served up by a sushi train. That will, of course, sound crazy and romantic and probably plain stupid to the managerialists, and it sometimes does even to me, but I can't help thinking that there's more to life than bland, well-ordered, managed efficiency â the type of life the great captains of industry want to see everyone under them living but couldn't possibly live themselves. Anyone who knows the pampered rich understands that, even more than all their money, it's the conflicts and triumphs of the business world that give them satisfaction and meaning. Their lives are full of passion and struggle; their employees are expected to shut up and obey. That's what defeat looks like.

Barry has one more thing to show me. As we walk towards it, I remark on the cleanliness of the floor, which, as the cliché goes, looks like you could eat off it and not get sick. I hadn't expected that, having worked in many factories myself years ago and seen filthy drains, rats and deadly spiders everywhere. He says it's not the original floor. You see, when the old assembly line building was demolished, it was decided not to jackhammer up the rough, uneven old base but instead to cover it with sand and top it with three feet of smooth, new, sealed concrete.

(Sous les pavés, la plage! Under the paving stones, the beach!)

It's an archaeologist's dream, like a brontosaur falling into a tar pit, and I tell him that thousands of years from now, if humankind is still around, and if all the written records of our time have rotted away and the digital archives have become corrupted or unreadable, someone may rip up this smooth floor and wonder what had changed, what sort of civilisation that concrete from 1999 had covered over.

We reach what Barry wants to show me: a giant mural of the plant from the late 1960s or early '70s, which he had personally saved from destruction when the old plant was being closed down. He's proud of it, and so he should be. There, smiling down on the workers from the far wall of the massive space, is their past. An amateur and not completely successful painting, it is at once industrial and verdant: a huge saw-tooth-roofed factory, with smoke coming from its boiler house chimney, standing in the middle of a vast semi-rural landscape that the city and its economy had yet to completely swallow up. Here was life in the industrial age, an age when not-so-dark and not-so-satanic mills sustained a life much different from the one we live today.

For some reason, the painting reminds me of those pastoral works by Poussin and others, where the happy and innocent peasants frolic among the revegetating ruins of a once great civilisation. Instead of being wantonly smashed to pieces by a ball on a chain, ground up with the factory's bricks and dumped somewhere as contaminated landfill, the picture hints at a life we no longer have â one many might argue was, in important ways, far better.

CHAPTER 2

THE SUBURB THAT WAS MURDERED

We look before and after,

And pine for what is not â¦

â P

ERCY

B

YSSHE

S

HELLEY

A

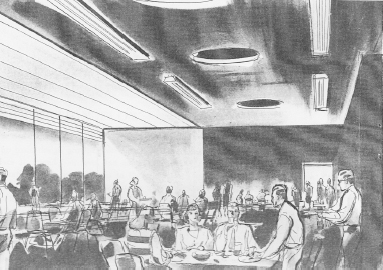

t the centre of any great place to work is a top-rate subsidised cafeteria. Anyone who has ever worked in a large organisation, with the possible exception of the federal parliament, can tell you this. Just ask a journalist in a great newspaper, a student in a great college, a machine operator in a great factory. The cafeteria is the place you look forward to, a place to escape the job for an all too brief moment, talk with friends, have a cup of tea and of course eat. Boyfriends and girlfriends eye each other across the tables, dates are arranged, hens' and bucks' nights are organised, wedding invitations are handed out, and photographs of babies and grandchildren are swapped.

The H. J. Heinz factory in Dandenong, just next door to the GMH plant, had a truly great cafeteria, and for twenty years beginning in 1972 my mother operated the cash register there, which put her at the heart of a self-contained little world. As you entered the factory, waving at the security guards as you passed through the gate, the cafeteria stood to the left. You couldn't miss it; it was another of those 1950s modernist designs that would have looked as appealing to the assembly line workers back then as the palatial entry halls of office towers do to accountants and merchant bankers today. (Today the professionals work amid beauty, while workers toil in cheap, functional, concrete prefab boxes; it wasn't always so one-sided.)

I have in front of me the official record from the factory's opening ceremony, held on 7 November 1955 and attended by Prime Minister Robert Menzies. A whole page is given over to what are called STAFF AMENITIES.

Modern and pleasant staff amenities are provided, with an entire building devoted to this purpose. In this building are lockers, toilet rooms, showers, etc., with each employee provided with an individual locker; a Cafeteria with a seating capacity for 500 people and where a wide variety of food is served, providing a pleasant and restful room for all employees to enjoy lunch and tea-time breaks. A well-equipped First-Aid section is included in this building and a qualified nursing staff is maintained whenever the factory is in operation. With this new Factory providing every modern facility, we look forward to a long and prosperous association with the communities of Berwick and Dandenong.

The Heinz cafeteria: paradise to parking lot â¦

What strikes you from this passage â apart from the fact it is written in clear prose, not the public-relations jargon of today â is the lengths to which companies like Heinz felt they had to go in order to impress unskilled factory hands. We must remember that factories like these were built in an era when capitalists knew they had to be nice to working-class people if they wanted them to work for them, and when they still felt a moral obligation of sorts to make their employees feel happy; at the very least, they calculated that happiness would make their employees more industrious. Note that the cafeteria had to be âpleasant', and that breaks were to be âenjoyed'. Can you imagine a workplace for the working class being designed with such sentiments in mind now? Another era indeed.

In the cafeteria, tea and coffee were free, and three meals were served a day, including a cooked breakfast if you were the sort who could get to work early enough. You could get a three-course meal at the lunch and evening sittings, including soup, full roast dinner with choice of meat, potatoes, fresh vegetables and salads, plus dessert. Many people regularly had their main meal at work because they liked it so much. I remember the cafeteria well because I once regularly ate there too.

For working-class university students like me back in the early to mid-1980s, the end of semester meant one thing: shift work. Education had opened our eyes to wider possibilities, and lying on the beach in Queensland with my new friends would obviously have been far preferable, but the money was fabulous â or at least it seemed so at the time â and turning it down was inconceivable. (This was, of course, in the days before universities got so expensive that even middle-class students had to work in low-paid service industry jobs all year round.) In retrospect, I feel fortunate, because across many sites, sometimes for up to six months at a time, I got to know factory life.

One day during the summer holidays leading up to my third year of university, my mother happened to tell the head of the factory laboratory while he was paying for his lunch that her student son was looking for work; did he have anything suitable? It just so happened that he did, and soon afterwards I found myself part of the tomato season casual intake. The word

laboratory

probably leads you to think I was filling test tubes in an antiseptic room alongside scientists. Wrong; I was a sort of go-between for the lab and the production floor.

My task was to operate a huge industrial kettle the size of a delivery van. Perhaps seven or eight times a day I would climb up a metal staircase, pour a bucket of a selected variety of tomatoes into the kettle (for some reason I remember UC-82s, which were oblong and harder than ordinary tomatoes), add given amounts of water, reduce them down to a set volume of pulp â a process which took around half an hour â and run a sample from it through the factory to the lab, where it would be analysed for sugar levels, viscosity and other qualities that would help make better tomato sauce and baked beans.

As factory jobs went, it had its benefits. On my way to the lab with my tomato samples I could stop and talk to my sister Dawn, who worked with her friends on the packing line watching cans full of cooked food move along a clanking conveyor belt. (My other sister, Pamela, worked at the Cadbury factory.) I could wave to my mother's partner, Fred (my parents had separated in the mid-1970s), who was a forklift driver. Or I could talk to one of the young female lab assistants my mother seemed to approve of more than my then girlfriend. Occasionally I would get squirted with water by one of the factory cleaners, who later served as a minister in the Rudd government.

While the tomato pulp was boiling down, there was little to do apart from tidying up and filling in a few forms, which enabled me to catch up on my university homework, so in fifteen- to twenty-minute blocks I would be standing up high on my machinery in my white overalls, working boots and earplugs (it was a loud factory, which I thought explained why my sisters always seemed to yell at each other, even when they were being friendly) and reading political philosophers like Karl Marx. I still have one of those books â an edited edition of

The Grundrisse

(in essence, the outline of

Das Kapital)

â which is stained with splatters of tomato sauce. (Flicking through it again now, I can see that this is where Marx outlined his own theory about the creative destruction inherent in capitalism, which Schumpeter developed further.)

Even at the time I thought it both an absurd and ironic image: the young proletarian intellectual reading Marx as he operated the very capital that was stealing his surplus value. But when you think about it, there's probably no better place to read socialist philosophy than on the factory floor, and no place more likely to make you realise that while working-class people could be bolshie at times, they were not natural revolutionaries. (Marx, of course, turned out to be partly wrong: my factory workmates were staunch Labor voters, and perhaps this groundedness explains why a lefty like me stayed in the moderate Left of the Labor Party, while the upper-class Marxists I knew at university slummed it for a while in Trotskyist sects before selling out and entering business.)

Back in the cafeteria, my mother was taking on capitalism much more effectively, not with revolutionary philosophy but with kindness. Her blind eye was routinely turned to the most important of rules. She always gave me too much change from my lunch, which everyone else knew full well and laughed at. Anyone who was short of cash to pay for their meals â usually younger workers who would blow their pay well before the end of the week â was fed nonetheless with mountainous portions and given an honour system; Mum simply recorded their debts in her little black book and entered the transaction on pay day. No one ever failed to pay. The manager knew of this ruse but officially pretended not to.

This sort of spirit was the oil that kept the factory running: people who had to suddenly leave work for an hour for important family or medical reasons were covered by their friends; those coming in late were occasionally clocked on and off by others on their shifts. If Fred had to start early, for instance, the managers looked the other way while he ducked home in the car to pick up Mum, who couldn't drive, so she could be there when the breakfast shift ended. Family members and friends were given jobs. (Do they call it nepotism at the big law firms and broking houses when the partners give their children a placement, then a job and then a partnership in the business?) Looking at the old factory newsletters today, a few things catch my eye.

BIRTHS To Dawn Sutherland (filling floor) and Andrew a daughter Tenisha. Grand-daughter to Audrey Glover (canteen cashier).

That's the announcement of the birth of my sister Dawn's first baby, my first niece, in 1989.

RETIREES Max Moore (fitter and turner Factory Engineering). Max gave more than 24 years' service to the company and almost as many as a shop steward representing his fellow employees. A tough negotiator, Max was principled and caring. He has purchased a new car and intends to spend some time travelling the country during his retirement.

That was the union rep â a part of the team, for all his faults. It's a good bet his new car had snaked past Dad on the assembly line in the GMH plant a few hundred yards away. He could drive it across Australia knowing it gave employment to his neighbours and friends.

THE NIGHT OWLS Engineering back shift consists of a team of 12 people under the supervision of Doug Tarbeck, with Roger Venn as Leading Hand. Including Roger there are four fitters, three trade assistants, an electrician and a greaser plus three services personnel, a boiler attendant, trimmer and a pump house attendant. It may be the nature of the job, or the people themselves, but working while others have gone to bed seems to encourage a certain independence of thought and self-reliance. Perhaps they become used to decision-making and sorting things out for themselves.

What follows are details of how the twelve had streamlined the night shift production processes, saving the company serious money. Here, the skills of working people and their contribution to efficiency and profit was well recognised by the management team. They didn't have degrees but it seemed they knew what they were doing and did it well.

There are also stories about the success of the three Heinz netball teams, the Heinz women's indoor cricket team, the Heinz running team and the twenty separate Heinz ten-pin bowling teams, whose season culminated in a grand final and an awards night at which everyone got a trophy; these factory workers didn't bowl alone. A long story covers the fun had at the end-of-tomato-season âAcademy Awards Night' for departing casual workers, organised by permanently employed volunteers. Even the casuals were treated like human beings by having their service acknowledged; often, if the managers could keep them on, they did.

Our little community's strengths extended beyond the factory gate. At bingo nights at the Dandenong Workers' Club, where many of the factory workers were members, someone in hard financial times might suddenly find that they had won the jackpot. When economists and accountants make up numbers to prove their absurd theories or mislead the taxman, society is the loser; at Heinz the faked figures were on the side of the angels.

That's how life was for the 1200 souls (up to 1600 at the peak of the tomato season) in the republic of Heinz back then. The economic reformers today would scoff and label their community-minded antics as inefficiency, luxury and âentitlement', and some of the more ideological analysts at right-wing think-tanks like the Centre for Independent Studies or the Institute of Public Affairs might even call it âtheft', but it's hard to see how such trifling indulgences could sink so large a battleship as Heinz. Indeed, the original calculation was that the sort of friendly work environment Heinz created and tolerated for so long would build a strong, loyal and hardworking workforce, and it's my bet that was right. But when the creative destroyers seized economic power in Canberra and began looking for award trade-offs, all that human decency, all that loyalty â all those things they couldn't measure and therefore regarded as worthless â had to go. What gets measured gets improved, as they say; everything else gets vaporised.

In 1992 the Heinz workforce was halved, and a few years later halved again. Dawn had already left to become a full-time mother, although she returned for seasonal work. Mum took a package at about this time. Fred took his in 1997, after thirty-five years of service. And then in 2000 the factory closed its gates for good. Seven weeks' pay and four weeks' for every year, up to a total of fifteen. So a maximum of sixty-seven weeks' pay â not bad for those who found other work straightaway, but for many it was the last full-time, permanent job they ever had. As Shakespeare might have put it:

This happy breed of men and women, this little world, this precious stone set in the silver sea ⦠this blessed plot, this factory, this company, this Doveton. All now gone.