An Economy is Not a Society (2 page)

Read An Economy is Not a Society Online

Authors: Dennis; Glover

You couldn't miss the factories â¦

I've travelled back to the site with Panda. After finishing school, we both went to Monash University, joining the Labor Party on the same day back in March 1982 (actually, I joined the Socialist Workers Party first but lasted just a couple of days). We've remained close ever since, although our paths diverged when we were in our mid-twenties: he became the local mayor and then a state MP and minister, while I went off to Cambridge.

At GMH, our dads were both probably representative of the factory workforce in its glory days: my father as a semi-skilled operative drawn to Australia by the promise of something better than could be found in the industrial cities of the United Kingdom, and Panda's as an unskilled peasant from southern Europe escaping from the poverty of a declining village and the oppressive rule of the colonels.

The factory life was in my father's blood. Like his brothers and friends, at age fourteen he had been apprenticed into the Hilden Mill in Lisburn, not far from Belfast. Built in the late 1700s, the mill was one of the very first steam-powered cotton manufactories, and the sort of workplace Friedrich Engels wrote about in

The Condition of the Working Class in England.

Having employed 2000 workers at its height, it closed in 2006; its ancient, gutted facade is now earmarked for an apartment development (which itself has been stalled since the global financial crisis took down the Irish housing construction industry). Dad described the mill, as it was in the early 1960s, as the sort of factory Charles Dickens would have recognised, with massive stationary engines driving spinning machinery via huge wheels and leather belts. His job as a hackle pin setter (a comparatively skilled occupation) was to repair the spinning machines in order to keep the production of linen fabric and high-grade sewing thread running efficiently. Dad's grandfather had been a labourer at Harland and Wolff shipyards, bashing thousands of infamously brittle rivets into the steel hull of the

Titanic

and its sister ships from the White Star Line.

This inheritance of industrial skills made my father valuable when he migrated to Australia in 1963, and gave him a free pick of available jobs. He'd started at the International Harvester truck assembly plant just down the highway, but soon moved to GMH, where the pay was better, and he remained there for most of the rest of his working life. Such were the people who built our country. Little did they know they were living out the final days of an industrial revolution that had lasted two centuries, until the factory smashers came.

Of the once mighty factory, just a few original buildings with their saw-toothed roofs remain. It's hard for Panda and me to make out exactly what used to be what, with little more than vague memories of factory Christmas parties to go by, so I return a few weeks later with Ian McCleave, a former engineer who became one of Holden Australia's most senior executives, and Russel Nainie, who rose from the factory floor to be one of the company's senior engineers. What remains isn't the old car assembly line but the former HSPO buildings and those that once housed the maintenance and tooling operations. We put on some fluoro vests and hard hats I'd borrowed from a friend who runs a small refrigeration factory in Spotswood and walked in.

It's a strange sensation, re-entering the past to find it echoing and empty. The main feature of the place is the serrated roof, the verticals containing giant windows like those of ancient cathedrals to let in the maximum amount of natural light. This, combined with the vast floor area, gives you the sensation of entering a roofed football stadium on non-game day or a hangar for jumbo jets that have already flown away. Apart from some shelving units at one end, it's completely empty. We continue our walk-through, pointing our outstretched arms here and there, trying to look like engineers on a plant inspection visit, and no one questions us.

As we look around, Russel tells me that under that one roof once worked at least 500 people, but during our tour I could see just five, and I think I may have double-counted at least one of them. It's part of some retail distribution operation, but there doesn't seem to be much going on. It's obvious why there's no security â there's really not much worth stealing, except for a boxed flat-screen TV and a few cheap-looking suits hanging from a wheeled clothes rack that looks like it's been forgotten.

On my earlier visit with Panda, we had crossed over to the other side of the building, which was joined to the spare parts operation by a covered driveway complex. It's here John thinks his dad might once have worked, pushing his broom back and forth down the aisles, smoking the innumerable cigarettes that failed to kill him until he reached ninety-one. We'd managed to find a storeman, who was sympathetic to our story about wanting to tell the plant's history but who â regulations being what they are â couldn't let us in because there were forklift vehicles at work somewhere. When Panda asked him what they were storing, he told us it was sacks of plastic pellets for use in plastic moulding, but he didn't know who used them and what they made. We thanked him and peeked inside to take some photos, which he allowed us to do from behind a chain.

It all had the sort of sad, impermanent air of a place not being used for its intended purpose. When one thinks about the investment that went into the plant's creation, and its fit-out with once edgy industrial technology â much of it paid for by the nation through its subsidies and protection â you can't but feel an immense sense of pathos at how it has all ended up. What a waste. John and I walked through its cavernous remains like visitors through the sacked ruins of Rome. The almost infinite emptiness and solitude begged the question: where had all the jobs gone?

Where have all the jobs gone?

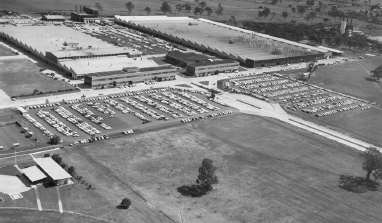

Ian and Russel take me on a walk around the site to look at what remains from its heyday. You can see it on this aerial photograph from 1970:

GMH, an archaeologist's dream â¦

Three smaller buildings, now used for warehousing, are all that stands from that time, along with the administration offices at the front of the old canteen. The then modernist structure, built in the late 1950s or early '60s, has been re-clad in glass and metal to bring it up to date; needless to say, this has ruined it completely. So many people had worked there â 5000 at one point â that the old canteen had staged three lunch sittings during the day shift alone. There was also a bank branch, a fishing club, a bowling club, a tennis club and a cricket club; the courts, greens and pitches were kept up by the factory's very own curator. I must have played cricket there as a sixteen-year-old.

No fewer than ten tea ladies were employed to roam the factory floors for elevenses and afternoon tea, which, until some time in the 1980s, was provided free to all employees. When the tea ladies were sacked, coffee vending machines with small plastic cups were installed and a dollar was added to everyone's weekly pay packet to cover the expense â one of the easy Tier 1 trade-offs during one of the innumerable accord agreements of those days. It's a small detail, but crucial when you think about it. If the past was so much poorer than the present, how could they have afforded to give factory workers a cup of tea then but not now?

This strikes me as an argument with a much wider application: according to the economic reformers, we can't afford Medicare or the aged pension anymore either, even though they assure us that the reforms of the 1980s and '90s have made us richer than ever. What alchemy of wealth creation meant that those tea ladies had to join the dole queue, and that an enjoyable part of thousands of people's lives had to be cheapened and ruined? Why do we consider what replaced that past to be somehow superior, and why do we consider the past itself to be something to snigger and scoff at? These are good questions, which our managerialist friends and their boosters in the press would no doubt dismiss with the inadequate word âefficiency', before themselves contemplating the client-funded cocktail party and dinner on offer that evening after work.

When I recall my father's addiction to tea â which he would drink while still in his blue overalls at the kitchen table each afternoon after work, strong and stewed in his old metal teapot â I imagine how much he must have looked forward to the tea ladies' visits. Real tea! I'm suddenly touched by the thought of him, conscientious, hardworking, never offshoring his tax or turning his wage into a capital gain, putting down his clipboard and leaving his station for a hard-earned break, a difficult and rare smile breaking out over his face as he reaches out and says, âWhite, one sugar.' A lifter, enjoying a simple pleasure no longer available to the little people. What sort of person would take that away? An economic reformer, obviously.

Dominating this whole site today is something that is no longer there. The heart of any auto factory isn't its spare parts warehouse or even the tooling workshops with their lathes, skilled toolmakers and apprentices â it is the assembly line. Ian and Russel point me to where it used to stand. The building looks far too modern. Russel tells me that it's been re-roofed and is now the Australian headquarters of HSPO, or at least what's left of it for the foreseeable future, Holden having already announced that it will be ceasing domestic production in 2017. I spy the high fences and the manned guardhouse and quickly conclude that there is absolutely no chance I can bluff my way in, even if I put on my hardhat and carry my clipboard. But where there's a will, there's a way.

A couple of weeks later I'm driving in, past the friendly and busy guard, to my appointment with Barry Crees, manager of the HSPO complex. Ian has sorted it out for me. While I wait for Barry, I notice that in the space of just a fortnight the construction opposite, which had been rising out of the old truck assembly plant, has gone from a metal frame to a roofed and almost fully walled building; as I watch, a crane lowers on another giant concrete panel. (By the time I leave the plant an hour later, the panel had already been bolted on to form a wall.) How many people will work in this warehouse, I ask myself. Building it has given a team of men work for a few months, but then what? Probably another building, and then another after that. If rapidly throwing up almost empty structures in a building boom is the only source of new jobs, then our economy and job market have become a sort of Ponzi scheme, where building after building needs to be constructed to keep us all one step ahead of the crash.

As we walk through to the warehouse, Barry tells me that the car assembly line plant has in fact been replaced completely. My heart sinks. I thought I'd be wandering across the original factory floor as it twisted around like a large intestine under the framework of the old aerial assembly line, going past the station where my dad worked fitting doors onto cars for almost thirty years.

The jobs of our fathers â¦