Among the Bohemians (49 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Lack of money could have been an inhibiting factor; it proved the opposite.

One way to save was by getting the guests to lay on the entertainment, and Bohemian parties had a large pool of talent to draw on.

With Bertie White or some other enthusiastic performer always eager to do a musical turn, one was rarely put to the expense of a band.

Once enough sherry or beer had been consumed someone was bound to start singing.

Mrs Varda, the proprietress of the eponymous Bookshop in High Holborn, kept the neighbourhood awake till the early hours by prolonged singing of ‘The Hole in the Elephant’s Bottom’.

Bunny Garnett remembered being delighted by the bawdy music-hall song ‘Never Allow a Sailor an Inch Above Your Knee’.

Nina Hamnett could be relied upon at any gathering to sing dirty songs or recite from her seemingly inexhaustible supply of rude limericks.

There were others too, prepared to do ‘turns’.

Betty May’s party trick was her performance as ‘Tiger Woman’ – she would go down on all fours and lap her brandy from a saucer.

Mark Gertler had wonderful powers of mimicry.

He could prostrate an audience by acting all the characters in some imagined incident: Lopokova being visited in her dressing room at the Coliseum by, in turn, Lady Ottoline, Lytton Strachey, Edith Sitwell and Maynard Keynes.

As one might expect, these parties were inventive and creative.

At Ford’s literary parties the guests competed for a crown of bay leaves by writing

bouts-rimés.

At Garsington the guests were persuaded to dress up and participate in

tableaux vivants.

Juliette Huxley was Beauty to Philip Heseltine’s Beast with a waste-paper basket over his head.

Party games were popular too.

A favourite chez Graves in Hammersmith was for a man and woman to eat a banana from opposite ends.

Unashamedly childish, a group of Bunny Garnett’s literary friends got down on the floor and played Hunt the Slipper round the Taviton Street bookshop that he co-ran with Frankie Birrell; searching beneath the stacks gave Boris Anrep ample opportunity for pinching the ladies’ legs.

At the Hutchinsons’ house in Hammersmith charades were the speciality.

Russia mania was at its height and, having improvised costumes from Mary’s dressing-up box, Gilbert Cannan appeared as the Czar, Viola Tree as the Czarina, Mark Gertler as the Czarevitch, and Boris Anrep as Rasputin.

Fancy-dress parties were ubiquitous.

Just for a night, one could be a Gauguin savage, Cleopatra, Jesus Christ, a Negro slave, an Athonite monk, Empress Theodora, a ringmaster or an acrobat.

The avant-garde found scope

for modish eclecticism here, as a palimpsest of face paint, embroidery, and gypsy finery restated the themes of experimental poetry, novels and art.

The modernist broke the rules, used allusions, drew from mythology, history and fragments of past literature for his or her creations.

Surely the contemporary craze for oriental robes and greasepaint was somewhere in Virginia Woolf’s mind when she wrote

Orlando

(1928), a novel which resembles nothing so much as a contemporary fancy-dress ball, whirling its hero/heroine through a bewildering series of chameleon-like transformations.

Nowhere in literature is the search for identity through disguise more fully expressed.

Where clothes cramped their style, Bohemians were nearly always prepared to dispose of them.

At the least provocation, and with a spirited lack of pomposity, party guests flung off their rags and tatters.

In 1910 ‘all the Slade gang’ attended C.

R.

W.

Nevinson’s twenty-first birthday.

Although on this occasion not much drink was consumed, the gathering was high on genius and anti-bourgeois sentiment, and at its height one of the dancers removed every stitch and danced naked.

‘At that time such a thing was as unusual as it is now commonplace, the only difference being that when I say naked I mean naked.’ Any really successful party included somebody stripped to the waist or beyond.

Kathleen Hale’s exuberant landlady was a literary agent who regularly bared her pretty breasts at gatherings for her clients.

Vanessa Bell ended up naked to the waist after dancing frenziedly at one pre-war party.

It seemed that all the Victorian hostesses’ worst nightmares were coming true.

One evening in the café Royal Nina Hamnett and her date got talking to a group which included a pink-faced young man in a white tie and top hat.

The toff was drunk, but eager to play, so they all went back to his place; at his family’s Holland Park mansion, only the cook was at home.

Soon the company were knocking back their absent hosts’ excellent brandy and wine, and discussing life and art.

The young man in the white tie was causing a good deal of disturbance in a corner.

Suddenly two members of the party shouted: ‘Take your clothes off!’…

The young man, who was apparently always willing to undress at a party on the slightest pretext, began slowly to take his clothes off.

Everyone had taken a violent dislike to him by this time.

Finally, he was entirely disrobed and stood with nothing on with the exception of a pair of black socks and smart button boots.

We all said: ‘Well, anyway, we like you better dressed than undressed.’

The situation degenerated further when another member of the party, a beautiful blonde in a purple silk dress, seized a walking stick with which she

attempted to attack their naked host.

He fled and she chased him round the table.

Just as she was about to catch him and flog him, he tripped headlong over the mat.

Later it came out that the cook had observed the entire spectacle through the dining-room keyhole.

This preposterous episode is typical of Nina’s reminiscences,

Laughing Torso

(1932) and

Is She a Lady?

(1955), both of which proclaim the author’s voracious lust for life.

Poor Nina succumbed eventually to alcoholism, but at her best she was one of life’s great enjoyers, irrepressibly bubbling over with vitality.

To me, one of the most sympathetic qualities that emerges from the accounts and memoirs of artists at that time is their sheer appetite for fun.

They had no taste for self-denial, passivity or ‘cool’.

They worked and played with equal zest, though often play took over from work.

Autobiographies like those of Nina Hamnett, Viva King, Beatrice Campbell, Bunny Garnett, Kathleen Hale and Brenda Dean Paul give the overriding impression of lives lived principally for enjoyment, at a time in history when it seemed that the gaiety was unprecedented.

Probably everyone feels these things when they are young; and yet that generation was surely riding the crest of a wave: impetuous, reckless and insatiable – but high on sensation.

*

In his old age my father was asked in an interview what had made him happiest in his life.

Quentin reflected before replying, ‘Being drunk, I think.’ He then modified this to, ‘Being

slightly

drunk.’

The bar has always been Bohemia’s natural habitat: Arthur Ransome’s ‘tavern by the wayside’, whose gaily painted sign tempts the wayfaring artist, inviting him to join the unconventional throng drinking within.

At the end of a chilly day working alone in one’s garret, how comforting and convivial it was to gather with friends in a bar, where music and a few glasses of beer or absinthe helped to dispel hunger, and numb the sting of failure, poverty and despair.

It would be warm and smoky and there was sure to be a friendly face – someone to commission a painting, inspire a story, or lend five shillings.

So synonymous with Bohemia did some of those meeting-places become that they have almost entered legend, their names evocative of louche romance.

Bohemia’s nightclubs in many ways epitomise what the respectable world most feared and resented about the libertarian life.

They were tainted by their dubious clientele.

Who were these deluded young people wandering the streets at night, drinking late, spending money, going out unchaperoned to dance and debauch?

Why were they not at home in the bosom of their families, in bed and asleep?

The fact was, the traditional family was in a stage

of painful transition, and the rearguard cited the growth of metropolitan nightclubs as scary evidence of degeneracy.

Clubs such as the Crab Tree, the Ham Bone, the Studio Club, the Golden Calf, the Gargoyle, the Cave of Harmony, the Harlequin, the Nest, the Bullfrog were springing up overnight.

There was an effrontery about their mushroom growth, their grotesque names, their lawless informality and their gypsy orchestras, that both frightened suburban matrons and threatened their very identity.

Clubs were nothing new – for men, at least; there was White’s, Brooks’s and Boodle’s.

The nineteenth-century ‘Bohemian’ clubber also had the possibility of joining the Chelsea Arts Club,

*

the Savage Club, the Langham or the London Sketch Club.

Slightly more informal – seedy velveteen coats and clay pipes being customary – these male preserves were nonetheless relatively orderly fraternities.

The members had a jolly supper, and told lots of jokes, and played tricks on each other, and even did comic pencil sketches on each other’s shirt fronts.

But they all caught the last bus home to their wives.

The new generation was bent on modernisation.

Evenings of friendliness didn’t have to be quite so frumpy.

The spirit of pre-war Bohemia was most flamboyantly captured at Madame Strindberg’s underground nightclub, the Cave of the Golden Calf.

Eric Gill had sculpted the idolatrous image which dominated the room and gave it its name; Wyndham Lewis, Spencer Gore and Epstein had also contributed to the decor.

The patronne was a dark-eyed wraith in white fur attentively greeting her guests, from impoverished artists to bankers and socialites.

An eclectic cabaret provided entertainment; there were folk songs and shadow-plays, Frank Harris reading Russian stories, or Betty May singing ‘The Raggle-tagglc Gypsies’.

As Osbert Sitwell remembered it:

This low-ccilinged night-dub, appropriately sunk below the pavement… and hideously but relevantly frescoed… appeared in the small hours to be a super-heated Vorticist garden of gesticulating figures, dancing and talking, while the rhythm of the primitive forms of ragtime throbbed through the wide room.

The Golden Calf was a victim of its own success.

It was raided for breaking the law in asking for payment from non-members, but London nightlife thrived against the odds.

The First World War saw an outbreak of nightclubs where survivors of the carnage could drink, dance and forget.

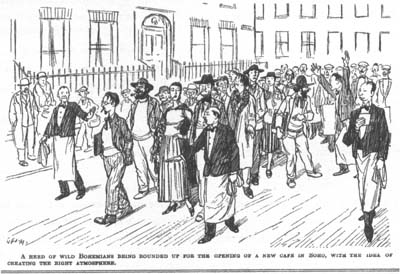

Degenerates or fashion leaders?

(

Punch,

8 October 1930).

In 1914 Augustus John helped to found the Crab Tree, a no-frills venue dedicated to hard-up artists.

Its Greek Street premises were reached via a complex of rickety staircases, down which drunks and brawlers were occasionally ejected.

The shabby interior was furnished with unvarnished wooden tables and chairs.

There were no waiters, and often nobody to take money, but anyone who turned up in evening dress was fined a shilling.

This went to subsidise the simple food, absinthe and cigarettes.

The entertainment was usually home-made, provided by the talents of the members – modern poetry recitals, songs, boxing matches.

After the Armistice, the mood of celebration propagated a whole new crop of clubs.

There was a huge demand; everywhere ‘Bright Young Things’ were deserting ballrooms and going on to more disreputable venues to dance till late.

There was the Ham Bone – crowded, slovenly and ‘chronically Bohemian’.

Over its bar hung a notice:

Work is the Curse of the Drinking Classes.

There was the Cave of Harmony in Gower Street, opened in 1924 by the cabaret artiste Elsa Lanchester, Klimt-like with her orange curls, green eyes and starveling figure.

Here, though one could not get alcohol (one had to go to the neighbouring pubs for that) one could foxtrot, enjoy the fruity re-wordings of Victorian love ballads performed by Elsa and the actor Harold Scott, and hobnob with painters and writers till 2 a.m.

Most famous of all, there was the Gargoyle Club in Meard Street, an obscure Soho alley.

Accessible only by a ‘Lilliputian’ lift, its glittering recesses were decorated by Matisse with fragments of antique mirror-glass rescued from the salon of a French chateau.

The wealthy socialite David Tennant started the Gargoyle as an ‘ “avant-garde” place open during the day where still struggling writers, painters, poets and musicians will be offered the best food and wine at prices they can afford.

Above all, it will be a place without the usual rules where people can express themselves freely.’ The Gargoyle’s membership was a roll-call of Bohemia – Dylan, Caitlin and Augustus, Michael Arlen, Nina, Ruthven, Nancy Cunard, Brian Howard, Cyril Connolly, Tennants and Mitfords, Stracheys, Partridges, Bells, Sitwells.

*

The association of various clubs with a Bohemian clientele extended to certain restaurants.

Many were cheap and cheerful Soho eateries like Bertor-elli’s or Bellotti’s – but the Eiffel Tower, like its namesake, surmounted all.

‘Discovered’ by Augustus John and Nancy Cunard one snowy night, the Percy Street restaurant soon became Bohemia’s favoured haunt.

For Nancy nothing short of apotheosis was good enough for it, as she expressed in the last verse of her ode ‘To the Eiffel Tower Restaurant’: