Among the Bohemians (47 page)

Read Among the Bohemians Online

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Tags: #History, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social History, #Art, #Individual Artists, #Monographs, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural

Women, above all, faced a lifetime of behavioural constraints, fenced in on all sides by the complexities of etiquette.

In the higher social classes, little girls were confined to the schoolroom from the age of five; at seventeen or eighteen, ‘ripe for the feast and battle of the world’, they were suddenly expected to put their hair up, lengthen their skirts, contribute to conversation, and ‘come out’.

This upper-class ritual was not a release however, but merely a herding from one kind of captivity to another.

The balls and dances at which a young lady and her chaperone was now expected to appear during the ‘season’ were regulated and selected with the aim of excluding socially undesirable elements.

Important lists were kept by every mother, of eligible men.

Once a man was on such a list, he was automatically invited to all the ‘good’ dances.

To many these occasions seemed overwhelmingly tedious and pointless.

For Allanah Harper the platitudes of the ‘list-men’ made irksome listening: ‘Jolly good band, what?’; ‘Yes, and the floor’s divine too’.

Mary Clive’s face muscles would go into spasm as she tried to think of remarks to make to the ‘fish-faced’ individuals kicking her shins while Charlestoning across some flower-banked Mayfair ballroom (‘how was it possible for mortal men to be so ugly?’).

She longed for the band to get drunk or the floor to give way so that they could have a topic of conversation.

Standing neglected in a queue for supper Mary often wished she were dead.

Marriage, the

raison d’être

of all this stultifying monotony, often turned out to be yet another social cul-de-sac.

If they weren’t supervising the housework or dealing with the servants, married ladies were sitting at home doing fancy needlework or painting tea trays.

Until the turn of the century, restaurants and nightclubs were not considered respectable for either women or men, and pubs were completely out of bounds.

‘Fork luncheons’ and formal dinners were the rule during the season.

After a seven-course meal stuck beside some tongue-tied bishop, it might well be a relief to follow the ladies’ procession to the drawing room.

Once there, the conversation fell back on illness, children, servants and – as captured by Vita Sackville-West in

The Edwardians

– comparisons of other people’s parties: ‘Are you lunching with Celia to-morrow, Lucy?’ ‘Yes, – are you?’…’How too deevy’…‘Friday was ghastly’.

‘Ghastly! Horribilino!

And the filthiest food.’ ‘Where are you going to stay for Ascot?’ The men meanwhile pushed out their chairs, put their feet on the fender, and talked politics, guns, or money.

Within a fortnight of receiving whatever kind of hospitality, etiquette obliged one to write to, or preferably call on, the hostess.

On these occasions it was sufficient to leave a visiting card.

The streets of towns and cities seethed with ladies passing afternoons in this seemingly futile activity, but as a social code the leaving of cards carried heavy significance.

Much could be read into their appearance, the promptness of the caller, or their omission.

*

Meanwhile, out there in Bohemia, a forbidden life was resolutely being pursued in parallel to the world of fork luncheons and visiting cards, the more thrilling because of its illicit nature.

In wartime London, Nancy Cunard, Iris Tree and her fellow art-students from the Slade held clandestine parties in Iris’s secretly rented studio, which she had equipped with a supply of theatrical costumes and greasepaint.

There by candlelight they dressed up, read poetry, smoked cigarettes and talked

through the night.

Before dawn they would steal back to their parents’ Kensington and Mayfair fortresses, evading servants and awkward questions.

One morning, half delirious from a night of revelry, still dressed in chiffon and spangles, Iris and Nancy took a dip in the Serpentine.

Emerging bedraggled they found themselves confronted by a policeman who charged them, having taken their names and addresses.

That was the end of their freedom – but only temporarily, for they forged new latchkeys, broke out, and were soon back at the studio.

Now with great daring they trespassed on such unladylike territories as foreign restaurants in Soho, public houses, or the cabmen’s shelters where you could get coffee and saveloys at three in the morning.

They drank wine at the café Royal or champagne at the Cavendish Hotel in Jermyn Street, whose free-and-easy proprietress Rosa Lewis (‘Ma Lewis’) insisted on charging their consumption of Veuve Clicquot to some unknown plutocrat’s bill.

Iris Tree and Nancy Cunard enjoyed the best of both worlds.

Iris makes it clear in her memoir of Nancy that they did not fully make the break from their establishment backgrounds.

The Bohemian studio was a refuge from the tedium and empty inanity of the London season, and calls, and house-parties, but it was part of a titillating game these debutantes were playing.

‘Transition and danger were in the air’; so too were court balls, champagne and millionaires.

Nevertheless years later, when she looked back, Nancy’s elegy was not for Hawaiian dance bands or dawn in Hyde Park, for Chelsea Arts Balls or steeplechases, but for the friendship that bound them:

IRIS OF MEMORIES

Do you remember in those summer days

When we were young how often we’d devise

Together of the future? No surprise

Or turn of fate should part us, and our ways

Ran each by each…

This emphasis on friendship, on the familiar discourse between what Virginia Woolf called ‘congenial spirits’, was at the heart of Bohemia’s idealistic quest to live and love and create more truthfully.

Though he wrote it many years later, E.

M.

Forster’s manifesto for the individual in

Two Cheers for Democracy

(1951) touched on the quintessential Bohemian attitude: ‘If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.’ Forster believed that

each person’s right to love and live in liberty was of far greater importance than society and its structures.

Artists usually work in solitude, and therefore tend to be people hungry for reassurance.

It is likely that the rejection of formality and the replacement of family bonds with those of friendship by many artists arose from an exaggerated need for like-minded company.

Feeling different from the rest of the world is easier if one has other people to be different

with,

and the intensity with which Bohemia partied may have had something to do with its own sense of itself as a tiny minority, stripped of the familiar social props.

Bohemians who had cut adrift from the establishment still needed a rudder to their raft, and a colourful flag to wave.

If one was going out to break the rules, in however small a way, it was morale-boosting – and a lot more fun – to do so in company.

And, for the uninitiated, how shockingly different that company appeared.

Bohemians in public places were still liable to cause frissons of unease in those unused to the spectacle.

Ladylike Stella Bowen, fresh from Adelaide, blushed to be taken to pubs by her artist friend and landlady Peggy Sutton, feeling that she had sunk to the depths of low life.

She was horrified by Bohemian clubs where cropped women and feminine men sat at stained tables in open shirts and colourful pyjamas.

Back at the Suttons’ flat she would reel to find the bathroom occupied in the morning by some gorgeous creature with kohl-rimmed eyes who had climbed in at the window at 3 a.m.

having failed to get the last bus home.

Where were all the chaperones?

Within months Stella was relaxing into the studio atmosphere, drinking at Bellotti’s with Ezra Pound, falling in love with literary and artistic London.

Stuffy Adelaide was on the other side of the world, and she put it behind her for life.

I have always had a passion for parties if they are given with no ulterior motive but that of enjoyment…

she wrote in her memoirs.

A good party is a time and a place where people can be a little more than themselves; a little exaggerated, less cautious, and readier to reveal their true spirit than in daily life.

For this, there has to be an atmosphere of safety from exploitation – a sense that you are all amongst friends, and that nothing you say will be used against you.

Social ambitions are death to such an atmosphere, and so is the presence of even one person who won’t play, and remains coldly aloof.

During the First World War, when so many men faced the prospect of being blown up or gassed or having their limbs amputated, caution and social ambition seemed more pointless than ever.

Indeed it seemed like a good idea to dance while one still

could

dance.

As Zeppelins appeared over London, spectacular in the dazzling searchlights, Bohemia became wilder and gayer with a kind of mad abandon.

For Betty May, ‘… it sometimes seemed as if everyone one had ever known would be killed – one went on dancing and rioting in an effort to forget how dreadful it all was.’

No Bohemian party at this time was complete without the painter Ethelbert White wildly strumming his guitar and singing bawdy ballads, while his dizzy wife Betty gyrated in a non-stop gypsy flamenco.

‘It made one’s heart thump in time to hear “K-K-K-Katy, beautiful Katy” bashed out by Bertie White’s band,’ remembered Viva King.

At Lady Ottoline MorreO’s Thursday evenings the guests would often pile on fancy dress and bound around as her husband, Philip, played old music-hall numbers like ‘Dixie’ or ‘Watch your step’.

‘Once a week there was this outburst of gaiety and giddiness,’ recalled Ottoline.

‘Next day we relapsed into the weary monotony of the war.’ Best of all were Augustus John’s riotous Mallord Street parties, gatherings populated by artists, barmaids, pimps, policemen, and anyone who could be fished out of the pub to join in.

Caspar John, on shore leave from the navy, felt like an alien confronted by his father’s cohorts of queer friends: ‘I suppose they were Bohemians,’ he conjectured.

On these occasions Augustus got paralytically drunk; there were brawls, gropings, attempts on his guests’ virginity and eventual collapse in unheroic disarray on some divan with his legs apart.

At eleven o’clock in the morning of 11 November 1918 the booming of the maroons across London announced the Armistice.

The War had ended.

With one accord the citizens took to the streets:

When we heard the cheers outside I dropped my brushes and rushed out with Kathleen into the Hampstead Road, where we jumped on a lorry which took us down to Whitehall…

remembered C.

R.

W.

Nevinson.

With a thousand others in Trafalgar Square we danced, ‘Knees Up, Mother Brown’; then to the café Royal for food, where we were joined by a gang of officers, and drank a good deal of champagne, and raided the kitchens because the staff had knocked off work…

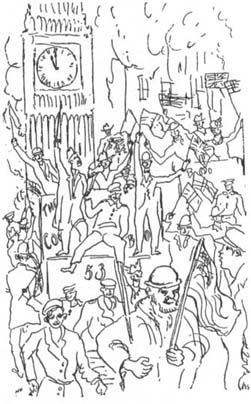

Celebrating the Armistice: another of

Nina Hamnett’s illustrations to

The

Silent Queen.

… then on to celebrate with his dealers, followed by a detour via the Studio Club, back on to the streets for more dancing, and back once more to the café Royal.

There Nevinson joined a group swarming like monkeys up the gilt pillars to the ceiling (‘often I marvel how this was done…’), then went on partying till the early hours at a picture dealer’s in Regent’s Park.

Osbert Sitwell was one of many who, over the course of the next week, fought his way through the crowds to the non-stop celebration being held by the barrister and art collector Monty Shearman at his rooms in the Adelphi.

He recalled this famous party in his memoirs: ‘Here, in these rooms, was gathered the élite of the intellectual and artistic world…’ Bohemia was there in force: Duncan Grant, Bunny Garnett, Nina Hamnett, Lytton Strachey, Carrington, Jack and Mary Hutchinson, Mark Gertler, Roger Fry, Clive Bell, Lady Ottoline Morrell, Frankie Birrell, Beatrice and Gordon Campbell, D.

H.

Lawrence, Lydia Lopokova and Léonide Massine, amid ‘a tangle of lesser painters and writers’, clustered around the imposing figure of Diaghilev himself.

Augustus John appeared with a posse of sexy landgirls in breeches.

Everyone danced, even Lytton Strachey, who appeared, as Sitwell recalled, ‘unused to dancing’; nevertheless there he was jigging about with an amiable debility’, reminding Sitwell of’a benevolent

but rather irritable pelican’.

Gertler threw himself around with Beatrice Campbell’s sister Marjorie, who took off her dress to cool down in the overheated room.

The industrialist Henry Mond stripped to his singlet to play the pianola, while the dancers poured champagne over him.

The Russians presumably eclipsed everyone else with their prowess.

To everyone here [remembered Sitwell], as to those outside, the evening brought unbelievable solace… No one, I am sure, was more happy than myself at the end of so long, so horrible, and so more than usually fatuous a war.

When the party began to draw to a close, I left the Adelphi alone, on foot.

In street and square the tumult born of joy still continued.

Smilingly, the people danced; or intently, with a promise to the future – or to the past, which weighed down the scales with its dead.