America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents (17 page)

Read America's Greatest 19th Century Presidents Online

Authors: Charles River Editors

Regardless, Jackson was inaugurated as the seventh President of the United States on March 4

th

, 1829. On his very first day in office, Jackson's uniqueness as a President was apparent. All prior Presidents had come from aristocratic backgrounds and were afforded quality educations. This was not the case with Jackson; unlike his predecessors, Jackson was a common man from the backcountry of the old Southwest. Previous inaugurations resembled the black tie affairs that accompany inaugurations today, but Jackson’s inauguration ceremony demonstrated his background; when common citizens were invited to the party, an uncontrollable mob broke into the White House and destroyed expensive china while celebrating. Fist fights also broke out in the upheaval. It was a very different type of celebration than any the White House had hosted...

Petticoat Affair

The “common man” Presidency encountered further problems with impropriety during its first months. In September of 1829, the “Petticoat Affair” broke out around a woman named Peggy Eaton, who by then had become the wife of Secretary of War John Eaton. Mrs. Eaton has been married to John B. Timberlake, a purser in the Navy. Timberlake was heavily in debt, but Peggy petitioned the Senate to pass a bill paying his debts. They did so, but Timberlake died shortly after, allowing Peggy to inherit his wealth.

Within weeks of her husband's death, Peggy remarried Secretary of War John Eaton. This was something of a scandal, as it was improper to remarry so shortly after losing a husband. Other wives of Cabinet Members, including the Vice President's wife Floride, raised concerns about Mrs. Eaton, accusing her of having an affair with Eaton prior to her first husband's death.

Mrs. Eaton

The affair shook Washington. Wives throughout the capitol demanded Mr. Eaton's resignation because of his moral scandal. Jackson, however, did not want to pass judgment on his Secretary of War and was wary about the use of wives in the political media. After all, he was still asserting that his own wife had died as a result of the attacks on her character during the 1828 campaign. But Jackson needed to settle the affair, which engulfed his young presidency and was a distraction so early on. Eventually he settled the problem through one of the backroom deals he had railed against years earlier. In 1831, Eaton resigned and Jackson appointed him to be Governor of Florida shortly thereafter.

As a result of the scandal, Jackson organized his “Kitchen Cabinet,” an informal group of advisors who he met in the White House. This was done in part in response to the break between Jackson and his Vice President Calhoun, who the President believed was fueling media opposition to Jackson. Calhoun had, supposedly, helped make the Petticoat Affair a national scandal. Jackson’s use of informal advisers instead of his actual Cabinet was derided in D.C., in keeping with the charge that Jackson was too much a commoner.

Indian Removal Act

In May 1830, Jackson signed his first major piece of legislation, the Indian Removal Act. The Act ordered that all Native Americans living in the southeastern part of the country had to be relocated to a designated “Indian Territory” west of the Mississippi River. For the remainder of the Jackson Presidency, the “Trail of Tears” would be ongoing, as the Native Americans of the southeast were brutally forced to move westward.

Jackson strongly disliked the Indian tribes living in the southeast, having fought them in the First Seminole War and the Creek War, so he had no remorse about forcing them westward. The Cherokee and other tribes, however, didn't flee without a fight. Instead of resorting to violence, which was likely to end in defeat and more brutality, they decided on a unique approach by attempting to rely on the laws of the United States to invalidate the Indian Removal Act.

While Jackson was in the midst of trying to enforce the Indian Removal Act, a case that involved neither the federal government nor the Cherokee was making its way up to the Supreme Court. The case involved the arrest of an American on Cherokee lands under a Georgia state law that prohibited non-Indians from being on Indian land. The Supreme Court ruled that the state law was unconstitutional because the state did not have sovereignty over Cherokee land. In laying out the ruling, Chief Justice Marshall wrote that the Cherokee was a sovereign nation, so negotiations between Native American tribes and the United States would be between that of nations, with states having no ability to enforce laws. Under the ruling, Native American tribes, as sovereign nations, would need to agree to move, with the negotiations being between two nations. In effect, the Court ruled the U.S. government had no authority to tell them what to do.

Naturally, Jackson didn't like what the court had to say. One of the quotes Jackson is best known for, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it”, is an apocryphal reference to this case. While he did not exactly say that, he did comment on the case to a friend, “The decision of the Supreme Court has fell still born, and they find that they cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate.” Jackson thus ignored what Marshall had written and moved ahead with the Indian Removal Act, ordering the state of Georgia to forcibly remove the Cherokee. In a stunning and dangerous break with American Constitutional law, Jackson argued that the court had no way of enforcing its mandates, so the President was free to do as he pleased.

The Cherokee and other southeastern Indian tribes were thus forcibly moved westward to modern-day Oklahoma, and thousands of Native Americans died along the journey. Notable critics in Congress were outraged, including Henry Clay of Kentucky and John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, who both thought the Act was a stain on American history. They also lambasted Jackson as an ignoramus, backcountry hick who had no restraint or respect for the rule of law. His complete contempt of the Supreme Court of the United States was taken as a dangerous precedent. Over the course of his Presidency, this would lead the National Republicans to strongly detest Jackson, labeling him “King Jackson.”

Nullification Crisis and Reelection

In 1832, the issue of tariffs on the importation of foreign goods nearly ripped the nation apart and ignited a civil war three decades before one actually occurred. Four years earlier, a tariff had been passed that taxed the importation of manufactured goods, many of which came from the industries of Great Britain. This tax was passed with the intention of protecting industry in the Northern states from competition from foreign industrial countries. The South, however, was less industrial and relied on the export of cotton; by reducing the competitiveness of British industry, the economy there was less able to afford to import cotton from the United States. To the South, the protective tariffs were one-sided and supported the North at the expense of the South, and the region loudly opposed them.

In 1832, a new tariff was passed that was less harsh than the one from 1828, but the South still opposed the bill. In response, South Carolina began to consider passing an ordinance of nullification, prohibiting the tariff within its borders. Vice President Calhoun encouraged the act, and supported its Constitutionality. On November 19

th

, South Carolina adopted the Ordinance of Nullification, overturning the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 within its borders. It also vowed that any attempts to enforce the law within its borders would lead to the state's secession from the Union.

Modern American jurisprudence has ensured that federal laws are supreme to state laws when they are in conflict, but South Carolina’s assertion that it had the ability to nullify a federal law dated all the way back to the “Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions”, which were drafted by Jefferson and Madison. Together, the two drafted the first major political documents advocating the rights of the states to nullify federal law that the states believed was unconstitutional. Citing this doctrine of “nullification,” various states in both the North and South asserted the states’ rights to consider federal laws invalid. The Resolutions sought to nullify the Alien and Sedition Acts within those states back in the late 18th century, Northern states debated nullification during the War of 1812, and in 1860, Southern states would take nullification one step further to outright secession, leading to the Civil War.

Amid the crisis, Jackson was reelected by a wide margin. He did not, however, win the state of South Carolina, which nominated its own candidate, John Floyd of the Nullifier Party. Within less than a week of his reelection, Jackson stated his position on the Nullification Crisis. He said that John Calhoun's doctrine of Nullification was an “impractical absurdity,” defied Constitutional law, and was tantamount to treason. President Jackson absolutely denied that a state had the right to overturn federal law, and he committed the U.S. military to quelling any attempts to do that in South Carolina. Ten days later, Vice President Calhoun resigned, having won a seat in the U.S. Senate, and he continued to support Nullification throughout the crisis.

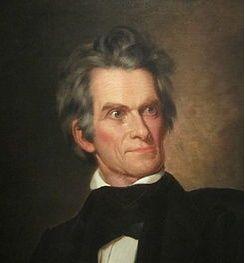

Calhoun

To give added support to his demands, the President asked Congress for an authorization to use force in January of 1833. On February 20

th

, Congress passed the Force Bill, known as the “Bloody Bill,” which authorized Jackson to use military force in South Carolina. Jackson went beyond this, vowing to personally murder John C. Calhoun and “hang him high as Hamen.” Such belligerent militance was typical of President Jackson.

Eventually Congress managed a compromise in March, authored by the “Great Compromiser” Henry Clay himself. The new bill reduced all tariffs for a ten year period and was signed into law on March 15

th

. South Carolina revoked its Ordinance of Nullification, though it nullified the Force Bill in the same act. Regardless, the Nullification Crisis was over.

The Second Bank of the United States

Jackson's reelection did not come at a politically peaceful time for the United States. In the summer of 1832, both houses of Congress passed a bill to re-charter the Bank of the United States, whose current 20-year charter was up. The First Bank of the United States had been one of the original issues that helped form the political rift between Hamilton and Jefferson that created the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties, but it had been re-chartered even with a Democratic-Republican in office in the early 19

th

century.

Jackson, however, was a staunch opponent of the bank and vetoed the bill to re-charter the Second Bank of the United States. Much as Thomas Jefferson opposed the First Bank of the United States, Jackson thought the bill benefitted rich Northern industrialists, not the common man on the frontier. Nicholas Biddle, the Bank's President, tried to mobilize support in Congress to pass the bill over the President's veto, but his attempt failed, creating a national controversy over the unsettled status of the country's central bank.

Despite the bank's charter not being renewed, the Bank of the United States was a partly private institution that could continue to function whether the government supported it or not. Its original charter, authored by Alexander Hamilton, had created a private entity that would only partially rely on some government support, as a way to assuage the concerns of Jefferson and his supporters that the bank would give the government too much power. Given this private status, as long as deposits remained in the bank and individuals wanted loans, the bank would continue to survive whether Congress authorized it or not.

Jackson was not content with just vetoing the Bank Bill; he wanted to kill the bank altogether. To do so, he decided to remove all federal government deposits from the bank. On September 10, 1833, after his reelection, President Jackson ordered that all federal government deposits be removed from the Bank of the United States.